This is the final post, at least for now, in a series called “A deeper look at the Will of William Henry Burke (1792-1870) ” . To re-cap slightly, my starting point for looking at William Burke was one of his sons-in-law Basil O’Bryen. Almost from the start of my research, Basil has been a source of fascination. Certainly a bigamist who abandoned his [second] wife and three children from two marriages. He appears to be fairly wealthy, though rather curiously, he seems not to be a beneficiary of his father’s will. Married at twenty-two to a woman ten years older, widowed, and remarried at the age of twenty-five. But, seemingly, well-thought of by William Henry Burke. As detailed in part four, I had gone to the National Archives to see whether Burke v. Keith could shed any light on the story. It does, and doesn’t, and here’s why.

The front page of the court case was a surprise.

1872-B-No 246 Filed 28th November 1872 pursuant to order dated 1st November 1872

In Chancery

between

William Henry Burke – plaintiff

and

Wilson Keith

Basil William O’Bryen, and Harriet Matilda, his wife

Mary Ann Burke, the wife of William Henry Burke.

and

William Donald Henry Burke

Edmund John Burke

Kate Alice Burke (spinster)

Sarah Elizabeth Burke (spinster)

Walter Keith Burke

all infants

Defendants

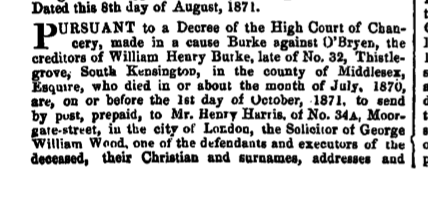

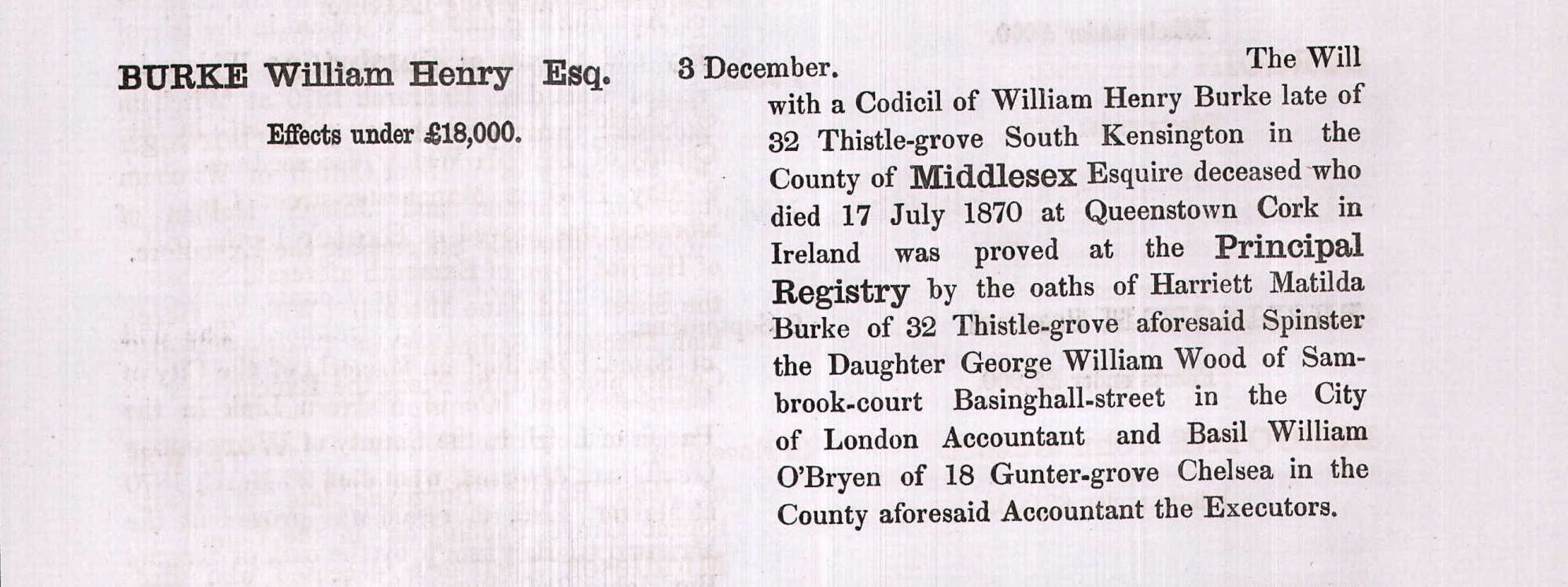

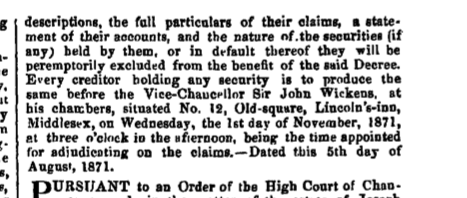

So Burke v. Keith and others is a case where Henry Burke is in a legal dispute with his sister, and two brothers-in-law, [Wilson Keith is Mary Ann Burke’s brother] and his wife, and children are also defendants in the case. Prior to this case, there had been the settlement of a caveat against the proof of WHB’s will by Henry Burke, and agreed in November 1870. More detail can be seen in “A deeper look at the Will of William Henry Burke (1792-1870) ” part four. Burke v. O’Bryen followed some time before August 1871, though very frustratingly I still don’t know what it was about. It is, however, safe to assume Henry Burke is still not happy, and, by 1872, Henry is back in court again. There is a reference to Burke v. O’Bryen 1871 B no 80, which he partly won, in the Burke v. Keith papers, where the Vice Chancellor Sir John Wickens “recognized his right to the residuary estate” but the order was expressly made “ subject to any arrangements the parties may have made between themselves as to the same”.

This time Henry is trying to get the trust for his wife and children set aside. To summarise some of the key parts:

William Henry Burke of 17 Newman Street, St Marylebone filed his bill of complaint in Chancery on 30th July 1872, amended 3rd October 1872. Essentially his complaint was against the trust his father set up for his daughter-in-law, and grandchildren.

“An indenture of voluntary settlement dated 6th May 1870 was made and executed between and by William Henry Burke since deceased the father of the plaintiff William Henry Burke of the one part and the said William Henry Burke the father, the defendant Harriett Matilda O’Bryen (therein called Harriett Matilda Burke), the defendant Wilson Keith, and the defendant Basil William O’Bryen on the other part as follows: – “

All their addresses are given, William and Harriett Burke are at 32 Thistle Grove, South Kensington, Wilson Keith “of Earls Court, esquire”, and Basil O’Bryen at 18 Gunter Grove, Chelsea. The settlement document was witnessed by John Roche O’Bryen at 28 Thistle Grove, and Corinne O’Bryen who was at 18 Thistle Grove on or about 6th May 1870.

The “ indenture witnesseth that in pursuance of the said recited desire on the part of the settlor and in consideration of the love and affection which the settlor has and beareth towards his daughter-in-law Mary Anne Burke, the wife of his son Henry Burke, and her issue by his son”

It’s all slightly strange, initially it seems to be WHB looking after his daughter-in-law, and some of his grandchildren. The question is why? Henry Burke was thirty-five years old, he was first a sculptor, and then set up his own firm W. H. Burke & Co., who were “at first sculptors and importers of marble and bronze before becoming one of the pioneering firms of the Victorian mosaic revival.” By 1871, he was occupying all of 17 Newman Street, just off Oxford Street ” these ‘very extensive premises’ included an octagonal modelling room and a large ‘marble yard’ extending behind the neighbours at Nos 18 and 19, reached via Newman Passage.” In the late 1850s the main premises had become the British and Foreign Marble Galleries of Edwardes, Edwardes & Co., boasting the largest stock in Europe of marble sculpture, and by 1865 were Henry’s workshops. In 1851-2, the octagon room had been used as a studio by Ford Madox Brown, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Henry Burke had been in partnership with the Edwardes brothers, and Alfred Edwardes was married to Henry Burke’s elder sister Elizabeth. Henry was recorded in the 1871 census as employing 28 men, and 1 boy. So he appears to have been doing quite well, so why did his father feel the need to provide for Mary Burke separately?

The settlement was arranged to pay Mary £ 300 a year in equal quarterly payments for her “sole separate and inalienable use” with a further caveat that if Henry becomes bankrupt then Mary Burke gets all the income over and above the £300 per year [using the same methodology as elsewhere in these posts, it is a modern-day equivalent of £ 224,000]. Otherwise, the rest of the income is to be invested until the youngest child is 24 or in the case of girls married. The trustees can dispose of assets as they see fit.

Henry and Mary Burke’s children were

- William Donald Henry Burke , then aged 10

- Edmund John Burke then aged 8

- Kate Alice Burke (spinster) then aged 6

- Sarah Elizabeth Burke (spinster) then aged 3

- Walter Keith Burke then aged 1

- and George Arthur Burke who died, aged four months, in July 1868

Henry claims that he is entitled to the residuary estate of his father, and the trust funds should be part of it because the length of the entail is so long as to make it ” void ”, and he should get the income apart from Mary’s £ 300 p.a.

This is where it all gets unbelievably frustrating. Three large archive boxes full of papers, most of which were un-related to the case, and crucially NO VERDICT.

It still sheds very little light on why twenty-two year old Basil O’Bryen was regarded as a suitable trustee. Wilson Keith, Mary Burke’s younger brother seems slightly better, but even then he’s only twenty-six. It does make one wonder if part of Henry’s case was simply pique at having to deal with two much younger trustees?