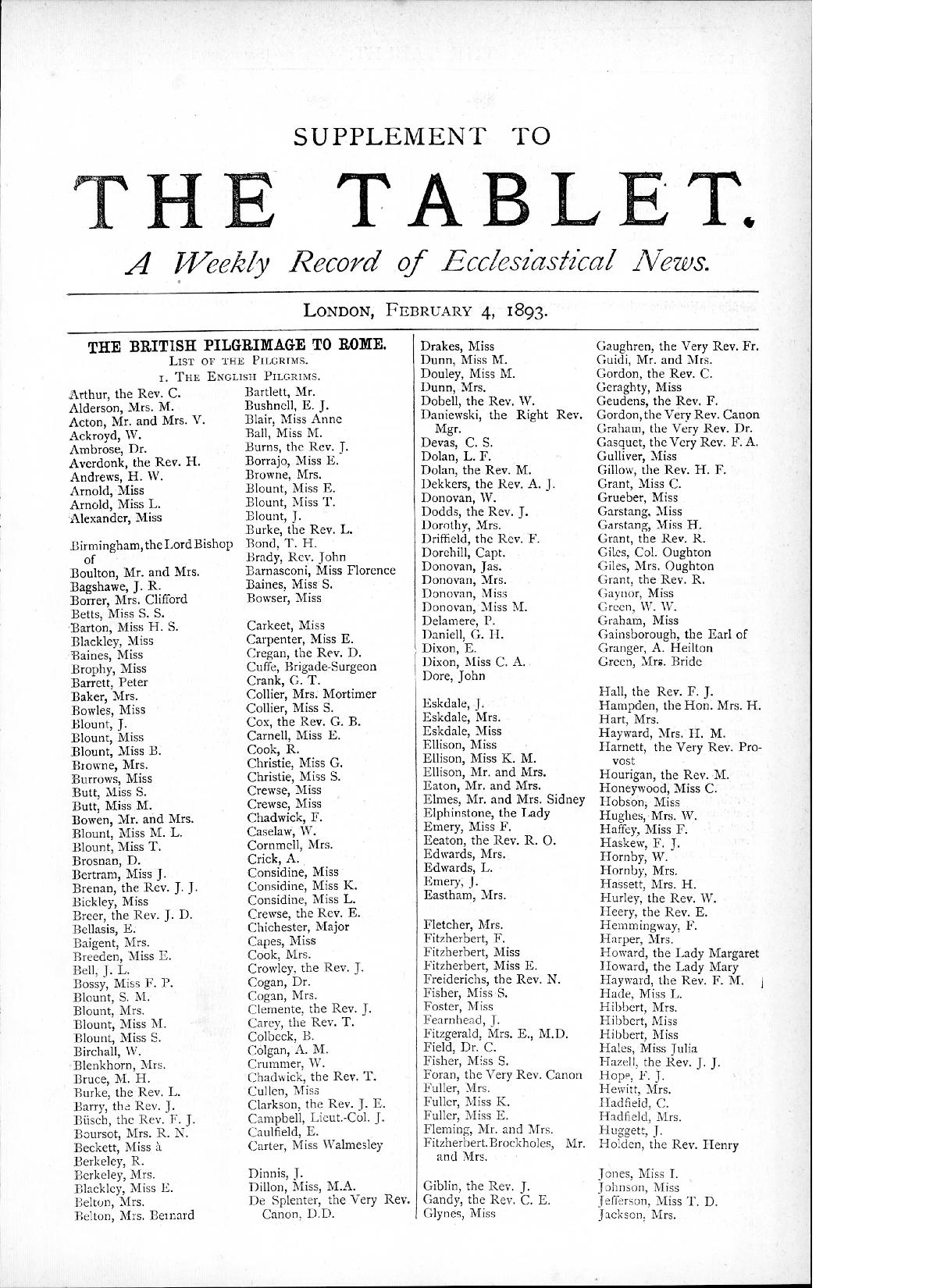

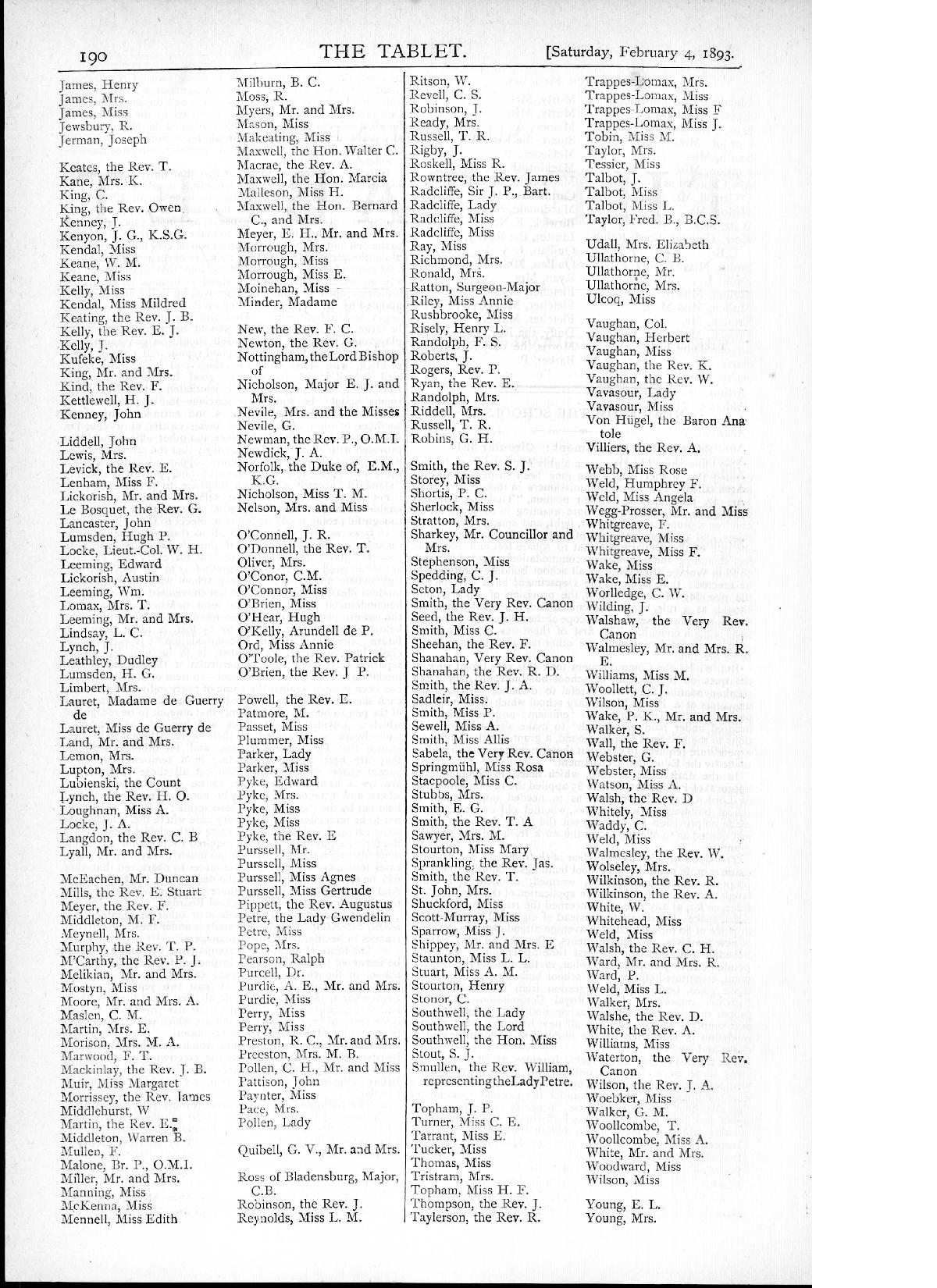

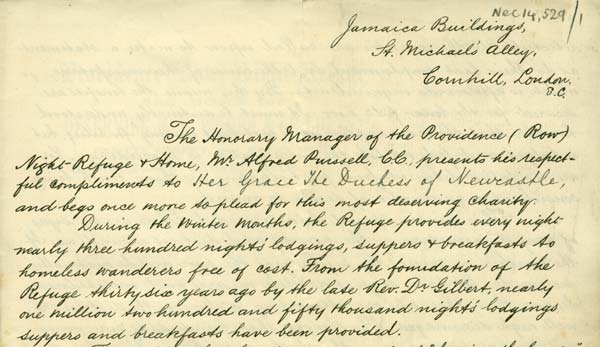

On the 4th of February 1893 the Tablet published a list of approximately 500 English visitors heading to Rome as pilgrims to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Pope Leo XIII’s consecration as a bishop. Amongst the pilgrims were Alfred Purssell, accompanied by Charlotte, Agnes, and Gertrude Purssell, then in their early twenties. The following text is an article from March describing the pilgrimage

THE RETURN OF THE PILGRIMS.

The great English Pilgrimage of 1893 is over and done with, and is already part and parcel of the indestructible past. Nothing can happen now to mar the perfect success of an enterprise which is safe from all hazard, because treasured away for ever in the memories of all who took part in it. The significance of this public demonstration of British faith and loyalty to the Holy See has been recognized and recorded in Rome for friend and foe, and in all the lands which were represented on that solemn occasion in the Eternal City. It was a time when the courts of the Vatican were thronged with pilgrims from all the earth, eager to do an old man homage ; when Cardinals were busied with splendid and stately ceremonial, acknowledging the courtesies of Kings, and the congratulations of nations, and the gifts of sovereigns—whether Emperors or Republican Chiefs ; but it is doubted whether any single incident during all the Jubilee gave Pope Leo a quicker and livelier sense of gladness than the sudden cheers which broke from 1,300 English and Scotch throats to greet him as he entered the Sala Ducale on Monday week.

For those ringing cheers which so astonished the members of the Papal Court, were tuned to the music of sincerity and so touched a chord which went very straight to the heart of the Pontiff. But that little separate incident in its thoroughness and simplicity, was a symbol of the spirit in which the pilgrimage was made. No such band of pilgrims ever left our shores, was so numerous, or so fully representative of the Catholic life of the country. Scarcely a Catholic family of note but was represented directly or indirectly. Following that of the Duke of Norfolk are ranged how many of the old familiar names, some of them of those whose fathers were true through all the trial, and were Catholic from age to age, and some of them of those who will be for ever associated with the coming of the second spring to Catholic England. The history of the Church in this country, whether in recent times or through the days of the penal laws, is inextricably bound up with that of the families represented at the pilgrimage. It is enough to cite in random recollection those of Howard, Clifford, Weld, Feilding, Stourton, Radcliffe, Noel, De Trafford, Townley, Vavasour, Maxwell, Vaughan, Whitgreave, Blount, Cox, Ridell, Hornyhold, Berkeley, Charlton, Southwell, Mostyn, Petre, Stonor, Wegg-Prosser, Dunn, Ward, Wolseley, Herbrt, Walmesley, Weld-Blundell, Ullathorne, Trappes, Lomax, Pollen, Neville, Hibbert, FitzHerbert, Ellison, Chichester, Bellasis, Acton, Arnold, Bagshawe—and other names as well known as these, will occur to the individual reader. But the pilgrims were representative of the future and the present as well as of the past ; as well of those who stand for the new streams of energy and industrial success and modern achievement, as for old family traditions. The accident of circum-stance in other years associated the story of hunted Catholicism with a handful of faithful families, the more vigorous and eager growth of the Church to-day covers a wider field, and depends upon newer homes which circumstances, essentially similar to those which operated of old, are now pressing to the front in the secular struggle of life. It was a happy characteristic of the present pilgrimage that it was a mingling of all classes, of the pro-mise of the future with the survivals of the past. From all parts of Great Britain, and from all sorts and conditions of men were gathered the pilgrims who rightly represented the Catholicism of the land. It was enough that all those widely-sundered hearts were united in their loyalty and love for the Holy See, and one common desire to win from Heaven a blessing upon their native land.

It is very pleasant to be able to put it on record that the returning pilgrims are loud in their appreciation and praise of the manner in which their wants and comforts were attended to by the Committee of Management, and in their gratitude to every member of it. The Duke of Norfolk, who has accustomed us to the sight of a willing effacement of all personal claims, uses our columns to tender thanks to others, both Englishmen and Italians, for their efforts to make the stay of the pilgrims in Rome pleasant to them.

It hardly needed the friendly importunity of a little crowd of pilgrims to induce us to offer to his Grace the thanks of all the Catholic body for the services and the example he gave. It has been a gracious labour to us to listen to the tale of gratification and pleasure which has come to us from so many pilgrims whose highest hopes have been more than fulfilled. Rome was seen at its best, on a great occasion, by people from all the ends of the earth, but to the British pilgrims it seemed that the Jubilee was in some sort a specially English festival. They were gathered there primarily to do honour and homage to Leo XIII. on the fiftieth anniversary of the day on which he was consecrated a Bishop, but the event, happily synchronized with the creation of an English Cardinal, and the magnificent function at St Peter’s was followed by that in S. Gregorio’s. The words of the Duke of Norfolk happily absolve us from the duty pressed upon us by many of the pilgrims of expressing to Cardinal Vaughan the enthusiastic thankfulness which his kindnesses and attentions have evoked, and we note them only as among the elements which went to secure the unqualified success of the Pilgrimage. Of course there were individual mishaps and disappointments, and, in some cases, privations and hardships to be endured,. but these private mortifications seem to have been suffered in a spirit of cheerfulness and resignation which is eloquent of the spirit which animated the pilgrims. The discomforts of a bad passage across the Channel, of a hurried but far from rapid journey through France and Italy, and difficulties about accommodation in Rome were things naturally to be borne in silence and patience. The fate of the few British pilgrims who in some momentary panic, caused by the cry that forged tickets of admission were being used, were shut out from the great function in St. Peter’s, must have been harder to bear without a murmur.

It was natural to expect that amid the general good humour of the pilgrims some comic incidents should be reported home. Thus much sympathy is expressed for the devout Highland chief who appearing in his national costume in the Corso, was placed under temporary arrest by the Roman police, in what appeared to be the interests of public decorum. The griefs of the Scotchman however, were soon forgotten for the woes of the young lady who, the day after the arrival of the pilgrims, got lost in St. Peter’s, and having forgotten the name of her hotel and speaking only Lancashire, got into an omnibus on the chance that if she saw her abode she might recognize it, and was driven about Rome for several consecutive hours.

Still better authenticated is the fate which befell an Italian who, as the Pope was borne up St. Peter’s, was imprudent enough to shout ” Viva Umberto I.” The creature thought he was insulting only the patient Catholics of the Continent. He was undeceived. A pair of Tipperary arms was round his neck in a moment, for another moment his heels were high in the air, and the next he was stretched flat on the sacred pavement. The crowd was too great to allow him to be put outside the Church, so two devout sons of Tipperary alternately sat and knelt upon him during the remaining hours, of the service. When the Holy Father had again blessed the people and returned to the Vatican, the Italian unharmed but terribly scared, was allowed to escape by his captors who though they caught the word Umberto had been unable to communicate with him.

The reception given by the Duke of Norfolk to the English, Scotch, and Irish pilgrims at the Hotel de Rome will long be a topic of conversation in Rome, and has led the Italian papers to indulge in some very fanciful conjectures as to what it may have cost. Certainly no such crowded reception was ever before held in that spacious hotel. Cardinal Vaughan’s reception at the English College, at which a large number of the Roman aristocracy were present, will also not soon be forgotten. The common bond of religion, for that night at least, was able to obliterate all the barriers of rank and race which men have set between men. Romans and foreigners from the British Isles, idlers and workers, rich and poor, all were there on a footing of Christian equality to do honour and accept the courtesy of the English Cardinal. Our last word before we conclude these recollections of the British pilgrimage is one which we would very willingly linger on. We are able to state that the piety and devotion of the pilgrims from Great Britain, as well as in the heartiness of their congregational singing, have made an excellent and a permanent impression in Rome.

The above text was found on p.5,11th March 1893 in “The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly.” Reproduced with kind permission of the Publisher. The Tablet can be found at http://www.thetablet.co.uk .