This was Percy Bysshe Shelley’s response to the Peterloo massacre in Manchester that took place 200 years ago today.

1

As I lay asleep in Italy

There came a voice from over the Sea,

And with great power it forth led me

To walk in the visions of Poesy.

2

I met Murder on the way–

He had a mask like Castlereagh–

Very smooth he looked, yet grim;

Seven blood-hounds followed him:

3

All were fat; and well they might

Be in admirable plight,

For one by one, and two by two,

He tossed them human hearts to chew

4

Which from his wide cloak he drew.

Next came Fraud, and he had on,

Like Eldon, an ermined gown;

His big tears, for he wept well,

Turned to mill-stones as they fell.

5

And the little children, who

Round his feet played to and fro,

Thinking every tear a gem,

Had their brains knocked out by them.

6

Clothed with the Bible, as with light,

And the shadows of the night,

Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy

On a crocodile rode by.

7

And many more Destructions played

In this ghastly masquerade,

All disguised, even to the eyes,

Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

8

Last came Anarchy: he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

9

And he wore a kingly crown;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone;

On his brow this mark I saw–

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!’

10

With a pace stately and fast,

Over English land he passed,

Trampling to a mire of blood

The adoring multitude.

11

And a mighty troop around,

With their trampling shook the ground,

Waving each a bloody sword,

For the service of their Lord.

12

And with glorious triumph, they

Rode through England proud and gay,

Drunk as with intoxication

Of the wine of desolation.

13

O’er fields and towns, from sea to sea,

Passed the Pageant swift and free,

Tearing up, and trampling down;

Till they came to London town.

14

And each dweller, panic-stricken,

Felt his heart with terror sicken

Hearing the tempestuous cry

Of the triumph of Anarchy.

15

For with pomp to meet him came,

Clothed in arms like blood and flame,

The hired murderers, who did sing

`Thou art God, and Law, and King.

16

We have waited, weak and lone

For thy coming, Mighty One!

Our purses are empty, our swords are cold,

Give us glory, and blood, and gold.’

17

Lawyers and priests, a motley crowd,

To the earth their pale brows bowed;

Like a bad prayer not over loud,

Whispering — `Thou art Law and God.’ —

18

Then all cried with one accord,

`Thou art King, and God, and Lord;

Anarchy, to thee we bow,

Be thy name made holy now!’

19

And Anarchy, the Skeleton,

Bowed and grinned to every one,

As well as if his education

Had cost ten millions to the nation.

20

For he knew the Palaces

Of our Kings were rightly his;

His the sceptre, crown, and globe,

And the gold-inwoven robe.

21

So he sent his slaves before

To seize upon the Bank and Tower,

And was proceeding with intent

To meet his pensioned Parliament

22

When one fled past, a maniac maid,

And her name was Hope, she said:

But she looked more like Despair,

And she cried out in the air:

23

`My father Time is weak and gray

With waiting for a better day;

See how idiot-like he stands,

Fumbling with his palsied hands!

24

`He has had child after child,

And the dust of death is piled

Over every one but me–

Misery, oh, Misery!’

25

Then she lay down in the street,

Right before the horses’ feet,

Expecting, with a patient eye,

Murder, Fraud, and Anarchy.

26

When between her and her foes

A mist, a light, an image rose,

Small at first, and weak, and frail

Like the vapour of a vale:

27

Till as clouds grow on the blast,

Like tower-crowned giants striding fast,

And glare with lightnings as they fly,

And speak in thunder to the sky,

28

It grew — a Shape arrayed in mail

Brighter than the viper’s scale,

And upborne on wings whose grain

Was as the light of sunny rain.

29

On its helm, seen far away,

A planet, like the Morning’s, lay;

And those plumes its light rained through

Like a shower of crimson dew.

30

With step as soft as wind it passed

O’er the heads of men — so fast

That they knew the presence there,

And looked, — but all was empty air.

31

As flowers beneath May’s footstep waken,

As stars from Night’s loose hair are shaken,

As waves arise when loud winds call,

Thoughts sprung where’er that step did fall.

32

And the prostrate multitude

Looked — and ankle-deep in blood,

Hope, that maiden most serene,

Was walking with a quiet mien:

33

And Anarchy, the ghastly birth,

Lay dead earth upon the earth;

The Horse of Death tameless as wind

Fled, and with his hoofs did grind

To dust the murderers thronged behind.

34

A rushing light of clouds and splendour,

A sense awakening and yet tender

Was heard and felt — and at its close

These words of joy and fear arose

35

As if their own indignant Earth

Which gave the sons of England birth

Had felt their blood upon her brow,

And shuddering with a mother’s throe

36

Had turnèd every drop of blood

By which her face had been bedewed

To an accent unwithstood,–

As if her heart had cried aloud:

37

`Men of England, heirs of Glory,

Heroes of unwritten story,

Nurslings of one mighty Mother,

Hopes of her, and one another;

38

`Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you —

Ye are many — they are few.

39

`What is Freedom? — ye can tell

That which slavery is, too well —

For its very name has grown

To an echo of your own.<

40

`’Tis to work and have such pay

As just keeps life from day to day

In your limbs, as in a cell

For the tyrants’ use to dwell,

41

`So that ye for them are made

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade,

With or without your own will bent

To their defence and nourishment.

42

`’Tis to see your children weak

With their mothers pine and peak,

When the winter winds are bleak,–

They are dying whilst I speak.

43

`’Tis to hunger for such diet

As the rich man in his riot

Casts to the fat dogs that lie

Surfeiting beneath his eye;

44

`’Tis to let the Ghost of Gold

Take from Toil a thousandfold

More than e’er its substance could

In the tyrannies of old.

45

`Paper coin — that forgery

Of the title-deeds, which ye

Hold to something of the worth

Of the inheritance of Earth.

46

`’Tis to be a slave in soul

And to hold no strong control

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

47

`And at length when ye complain

With a murmur weak and vain

‘Tis to see the Tyrant’s crew

Ride over your wives and you–

Blood is on the grass like dew.

48

`Then it is to feel revenge

Fiercely thirsting to exchange

Blood for blood — and wrong for wrong —

Do not thus when ye are strong.

49

`Birds find rest, in narrow nest

When weary of their wingèd quest;

Beasts find fare, in woody lair

When storm and snow are in the air,1

50

`Asses, swine, have litter spread

And with fitting food are fed;

All things have a home but one–

Thou, Oh, Englishman, hast none!

51

`This is Slavery — savage men,

Or wild beasts within a den

Would endure not as ye do–

But such ills they never knew.

52

`What art thou Freedom? O! could slaves

Answer from their living graves

This demand — tyrants would flee

Like a dream’s dim imagery:

53

`Thou art not, as impostors say,

A shadow soon to pass away,

A superstition, and a name

Echoing from the cave of Fame.

54

`For the labourer thou art bread,

And a comely table spread

From his daily labour come

In a neat and happy home.

55

`Thou art clothes, and fire, and food

For the trampled multitude–

No — in countries that are free

Such starvation cannot be

As in England now we see.

56

`To the rich thou art a check,

When his foot is on the neck

Of his victim, thou dost make

That he treads upon a snake.

57

`Thou art Justice — ne’er for gold

May thy righteous laws be sold

As laws are in England — thou

Shield’st alike the high and low.

58

`Thou art Wisdom — Freemen never

Dream that God will damn for ever

All who think those things untrue

Of which Priests make such ado.

59

`Thou art Peace — never by thee

Would blood and treasure wasted be

As tyrants wasted them, when all

Leagued to quench thy flame in Gaul.

60

`What if English toil and blood

Was poured forth, even as a flood?

It availed, Oh, Liberty,

To dim, but not extinguish thee.

61

`Thou art Love — the rich have kissed

Thy feet, and like him following Christ,

Give their substance to the free

And through the rough world follow thee,

62

`Or turn their wealth to arms, and make

War for thy belovèd sake

On wealth, and war, and fraud–whence they

Drew the power which is their prey.

63

`Science, Poetry, and Thought

Are thy lamps; they make the lot

Of the dwellers in a cot

So serene, they curse it not.

64

`Spirit, Patience, Gentleness,

All that can adorn and bless

Art thou — let deeds, not words, express

Thine exceeding loveliness.

65

`Let a great Assembly be

Of the fearless and the free

On some spot of English ground

Where the plains stretch wide around.

66

`Let the blue sky overhead,

The green earth on which ye tread,

All that must eternal be

Witness the solemnity.

67

`From the corners uttermost

Of the bonds of English coast;

From every hut, village, and town

Where those who live and suffer moan

For others’ misery or their own.2

68

`From the workhouse and the prison

Where pale as corpses newly risen,

Women, children, young and old

Groan for pain, and weep for cold–

69

`From the haunts of daily life

Where is waged the daily strife

With common wants and common cares

Which sows the human heart with tares–

70

`Lastly from the palaces

Where the murmur of distress

Echoes, like the distant sound

Of a wind alive around

71

`Those prison halls of wealth and fashion,

Where some few feel such compassion

For those who groan, and toil, and wail

As must make their brethren pale–

72

`Ye who suffer woes untold,

Or to feel, or to behold

Your lost country bought and sold

With a price of blood and gold–

73

`Let a vast assembly be,

And with great solemnity

Declare with measured words that ye

Are, as God has made ye, free–

74

`Be your strong and simple words

Keen to wound as sharpened swords,

And wide as targes let them be,

With their shade to cover ye.

75

`Let the tyrants pour around

With a quick and startling sound,

Like the loosening of a sea,

Troops of armed emblazonry.

76

`Let the charged artillery drive

Till the dead air seems alive

With the clash of clanging wheels,

And the tramp of horses’ heels.

77

`Let the fixèd bayonet

Gleam with sharp desire to wet

Its bright point in English blood

Looking keen as one for food.

78

`Let the horsemen’s scimitars

Wheel and flash, like sphereless stars

Thirsting to eclipse their burning

In a sea of death and mourning.

79

`Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war,

80

`And let Panic, who outspeeds

The career of armèd steeds

Pass, a disregarded shade

Through your phalanx undismayed.

81

`Let the laws of your own land,

Good or ill, between ye stand

Hand to hand, and foot to foot,

Arbiters of the dispute,

82

`The old laws of England — they

Whose reverend heads with age are gray,

Children of a wiser day;

And whose solemn voice must be

Thine own echo — Liberty!

83

`On those who first should violate

Such sacred heralds in their state

Rest the blood that must ensue,

And it will not rest on you.

84

`And if then the tyrants dare

Let them ride among you there,

Slash, and stab, and maim, and hew,–

What they like, that let them do.

85

`With folded arms and steady eyes,

And little fear, and less surprise,

Look upon them as they slay

Till their rage has died away.

86

`Then they will return with shame

To the place from which they came,

And the blood thus shed will speak

In hot blushes on their cheek.

87

`Every woman in the land

Will point at them as they stand–

They will hardly dare to greet

Their acquaintance in the street.

88

`And the bold, true warriors

Who have hugged Danger in wars

Will turn to those who would be free,

Ashamed of such base company.

89

`And that slaughter to the Nation

Shall steam up like inspiration,

Eloquent, oracular;

A volcano heard afar.

90

`And these words shall then become

Like Oppression’s thundered doom

Ringing through each heart and brain,

Heard again — again — again–

91

`Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many — they are few.’

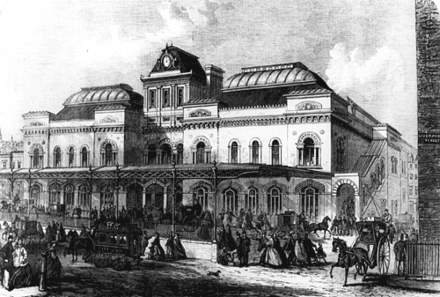

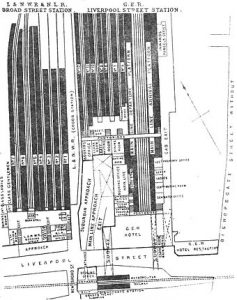

Broad Street station was next door to, and to the west of Liverpool Street Station. In fact one of the original entrances to Liverpool Street tube station is still in Broad Street. The remainder of the old Broad Street station is now the part of the Broadgate office complex.

Broad Street station was next door to, and to the west of Liverpool Street Station. In fact one of the original entrances to Liverpool Street tube station is still in Broad Street. The remainder of the old Broad Street station is now the part of the Broadgate office complex.