This post is a combination of extracts from The Life Of Sir Joshua Walmsley, By His Son, Hugh Mulleneux Walmsley. Chapman And Hall, 193, Piccadilly. 1879. and Thomas Burke’s ” Catholic History of Liverpool,” Liverpool : C. Tinling & Co., Ltd., Printers, 53, Victoria Street. 1910. Both are slightly partisan sources. Uncle Hugh’s biography of his father is uncritical to put it mildly, but it does quote his father apparently verbatim, which is nice. Tom Burke takes a pro-Catholic, and Irish Nationalist position, but that doesn’t detract from the power and polemic in his writing.

Education, as with so many other things, was a hornet’s nest of politics, religion, bigotry, racism, and class. The Municipal Reform Bill of 1835 had resulted in a huge landslide vote for the Reformers or Whigs giving them a total of 44 councillors and 15 aldermen, against only 4 Tory councillors, and a single alderman. Until the Reform Act Liverpool had always been a Tory corporation. So it was a radical change.

The first extract is Chapter IX of Hugh Walmsley’s book.

On the eve of the termination of the reform council’s first year in office, [November 1836] when, according to a clause of the Municipal Reform Bill, sixteen of its members were to go out, Mr. Walmsley read a paper, entitled, ” What has the new council done ?” In it he passed in review the abuses that had been found prevalent, and the Acts that had been framed. Notwithstanding the difficulties with which it had to contend, the Council had effected a saving to the borough fund of ten thousand pounds per annum. In this paper he also expounded the system by which the Educational Committee had opened the Corporation schools to all sects and denominations.

Let us glance at this act of the council, one that raised a storm in Liverpool, the like of which had not been known. Mr. William Rathbone and Mr. Blackburn took the lead in the movement. Mr. Walmsley devoted to it what time he could spare from the arduous task of reforming the police.

The feeling that impelled the Educational Committee to advocate the adoption in the Corporation schools of the Irish system of education, was awakened by the spectacle of the multitude of children in Liverpool debarred from every chance of instruction. The report drawn up by the committee showed that besides numerous Dissenters, there were sixty thousand poor Irish Catholics in the town. The old corporation had quietly ignored this alien population, but threw open the doors of the Corporation schools to children of all sects, provided they attended the services of the Established Church, used the authorised edition of the Bible, and the Church Catechism. This virtually closed these schools against the Irish. The new council maintained that the State had the same responsibility as regards these children as it had towards others ; and the Educational Committee drew out a plan from that of the Honourable Mr. Stanley, Secretary for Ireland in 1831, [later Prime Minister three times as the Earl of Derby] Dr. Whately, and others, for the education of the Irish poor. Early in July, the committee laid its scheme before the council. The schools were to open at 9 A.M, with the singing of a hymn. The books of the Irish Commission were to be used. Clergymen of every denomination were invited to attend at the hour set apart for the religious instruction of the children of the various sects. The town council unanimously adopted the plan and made it public.

The storm now burst over Liverpool, and crowded meetings were held at the amphitheatre and elsewhere, to protest against the Act, and to promote the erection and endowment of other schools, where the un-mutilated Bible would form a compulsory part of every child’s education. In vain the council invited its accusers to come and see for themselves, the un- mutilated Bible forming part of the daily education. The cry continued to be raised by the clergy, and to be loudly echoed by their agitated flocks.

” Dissenting and Roman Catholic clergymen came,” said Mr. Walmsley, ” eagerly, to teach the children of their respective flocks during the hour appointed for religious instruction ; but with the exception of the Rev. James Aspinall, the English clergy stood obstinately aloof. Soon, in addition to the meetings, the walls were placarded with great posters, signed by clergymen. These exhorted parents not to send their children to the Corporation schools, promising them the speedy opening of others, where the un-mutilated Word of God should be taught Some of the lower classes maltreated children on their way to the schools, pelted and hooted members of the committee as they passed. The characters of Mr. Blackburn, Mr. Rathbone, and my own were daily assailed in pulpits and social gatherings. Still we persevered, answering at public meetings the charges brought against us, and inviting our detractors to come and visit the schools. So particular was the Educational Committee that each child should be taught according to the creed of its parents, that every sect seemed represented. I remember one child, on being asked the invariable question on entering the schools, to what persuasion her parents belonged, answered, to the ‘ New Church.’ We were puzzled to know what the ‘ New Church ‘ was ; it proved to be Swedenborgian. She was the single lamb belonging to this fold, yet a teacher of her creed was found ready to undertake her education.”

To illustrate to what degree fanaticism blunts the moral sense of those who blindly surrender themselves to its influence, we quote the following fact : ” One day, when the hour of religious instruction had come, a clergyman of preponderating influence entered the schoolroom of the North School. The large room was divided into two compartments by a curtain drawn across it ; on one side were the Roman Catholics, on the other were the Protestants. The latter, divided into several groups, were gathered round different teachers. My wife, who seconded with all her heart this scheme of liberal education, was a daily visitor in the North School. She taught a class there — the Church Catechism and lessons from the authorised version of the Scriptures.”

“The clergyman made the circuit of the room, passing near each group. He at last approached my wife’s class and lingered near it. The lesson was taken from the Scriptures. It was no class-book of Biblical extracts she was using, but the Bible as it is used in the Protestant Church. The reverend visitor listened to the questions put and answers given, and to the children reciting their verses. The following Sunday my wife and I went to church. The preacher that day proved to be the clergyman who had a few days before visited the school. The sermon was eloquent, and, as usual, was directed against the spread of Liberalism and the ‘ Radical council.’ In the midst of the torrent of denunciation the preacher emphatically asserted that, some days before, he had visited the Corporation schools in the hour of religious instruction, and that no Bible was in use during that time.”

As the period drew nigh for the November election to replace the retiring third of the council, the religious zeal of the town burned higher. To the imagination of frightened Protestants, theConservatives presented themselves in the reassuring role of ” Defenders of the Faith.” They played the part so well that seven Tories replaced seven of the sixteen Liberal councillors who had retired.

Matters had now reached such a pitch that, at the next meeting of the board, Mr. Birch moved that the schools be discontinued, the property sold, and the Corporation trouble itself no more with the question of education. The proposition was so unexpected that the debate upon the motion was adjourned for a fortnight.

When the day for the debate arrived, the Educational Committee were ready to meet their opponents. In long and able speeches, Mr. Rathbone and Mr. Blackburn met and refuted every objection. They sketched the history of the mixed system of education, showed its essential fitness to the requirements of Liverpool, where the number of Catholics and Dissenters rendered the question of education as knotty to solve as the Government had found it to be in Ireland. They described the difficulties they had already surmounted, and earnestly pleaded that no change should be introduced into the committee’s plans until fair time for trial had been allowed it. Mr. Walmsley also spoke. He made no attempt to refute the quibbling assertions advanced against the system, but he went straight to the heart of the subject, to the humanity and justice that were the very core of it. This was no political or party question, but one in the decision of which the moral training and future welfare of a number of children were involved. He showed that one thousand three hundred children were daily taught in the schools; if the majority were Catholics, it proved only their greater need of schools. ” The result of giving them up,” he said, “would be to give up to vice and ignorance children whose hopes we have raised towards better things. It has truly been said that ‘ he who retards the progress of intellect countenances crime, and is to the State the greatest criminal.’ ”

By a large majority of votes, the council decreed that the mixed system should be continued in the schools.

In the month of August, 1837, Mr. Wilderspin, to whom the committee had entrusted their arrangement and organisation, announced that his work was finished. Before retiring, he wished an examination to take place of all the scholars. Clergymen attended to put the little Protestants through a sifting and trying ordeal. The result of this trial will be best expressed in an extract from a letter of the Rev. J. Carruthers. ” The examination proves that the teaching given is not of a secular kind, but on the contrary embraces an amount of instruction far exceeding what is usual in either public or private seminaries. The Bible is not excluded, is not a sealed book. The amount and accuracy of Biblical knowledge possessed is astonishing.”

Thus the children silenced by their answers the cry raised against the mutilation of the Scriptures. The innocent replies proved better than could the ablest defence, in what spirit the Educational Committee had worked, and in what spirit their enemies had judged their efforts.

Before separating, the audience who had been present, and who for the most part had come to criticise, united in passing a vote of thanks and congratulation to the Educational Committee for the work they had done, and for the excellent state of the schools.

We have dwelt at some length on this attempt of the council to establish a free and religious scheme of education in Liverpool, for it was destined to prove the rock ahead on which Liberalism was to split.

The following is from Tom Burke. The wording in brackets is from footnotes in the original; and he is calling the Reformers, or Whigs, Liberals, not a term they themselves would have used at the time.

Tom Burke tells us of ” the delicate relations between the English and Irish Catholics of the town, and the ease with which the susceptibilities of the latter could be touched in a tender spot. “

The differences were momentarily forgotten over the memorable fight for the schools at the November election of 1841. Somewhat prematurely the Liberal party announced that if returned to power they would build schools in every district of the town to be conducted on the same lines as the two schools already in existence. McNeill and his Tory followers paraded the streets with open [Life of William Rathbone, by Miss Eleanor Rathbone. ] Bibles attached to long poles, and strenuously appealed to the electors not to allow the erection of any schools unless Catholics and Dissenters would accept instruction from the authorised version of the Scripture. ” Converted priests “ harangued frenzied Protestant audiences, and were described by John Rosson, quoting Edmund Burke, ” as only qualified to read the English language,” and went on to say that as scholars they were ” despicable “ and as divines ” grossly ignorant men “ These Orange zealots forgot in their blind fury that the outcome of a Tory Protestant victory would be to force the Catholics to build schools for themselves, else they had never undertaken the campaign which aroused the worst passions of one section of the community and effectually destroyed for many years peace and harmony among the diverse sections which made up the Liverpool of the early forties.

Wild stories were put in circulation of the ” murder “ of seven Protestant clergymen in Ireland, which so inflamed the Orange population of Toxteth that they smashed up an anti-Corn Law meeting in Great George Place, confusing, in their frenzy, economics with ” Popery.” They then marched to St. Patrick s Chapel, and shattered the windows of both schools and church. The wife of a policeman was saying her prayers quietly in the church when the infuriated mob made the attack, and, as the consequence, lost her life from fright, an incident which increased animosity on both sides. The Conservative party, emboldened by the strife, demanded that no prayers should be recited in the Council schools save those to be found in the Anglican liturgy, and that no teachers should be appointed outside those who professed the Protestant faith as defined by Dr. McNeill. A lady had been appointed a teacher at the North Corporation School, on the recommendation of the Protestant Bishop of Ferns. Coming from Ireland, her orthodoxy was suspected and the Conservatives in the Council refused to ratify the decision of the Education Committee. The Liberals declared that they declined to make religious belief a test, but had no objection to informing their opponents that the lady in question professed the Protestant faith. On this assurance, and for ” the maintenance of truth,” the Conservatives withdrew their opposition. They had, however, secured their object, the ” maintenance “ of religious controversy, and had so well succeeded that they fought the elections with an air of confidence, which was abundantly justified by the results.

The Liberals were swept out of the Council by this whirlwind of passion ; only three being returned at the poll. Every retiring Liberal Alderman was ousted, and until 1892 the Liberal party remained in a hopeless minority. The Catholic Aldermen Sheil and Roskell, fell with their Liberal colleagues, and William Rathbone suffered his third defeat in Great George Ward. Flushed with victory, the Tories resolved upon a policv of making it impossible for any Catholic child attending further the Corporation schools. The educational treaty of peace was rudely torn up, never to be restored, as the Nonconformists very naturally were driven into bitter hostility against the party which had practically resolved to teach at the expense of the ratepayers, the authority of the Church of England. The elections were fought on the first of November, and by the first day of the following month the Catholics learned with dismay the intentions of the dominant party. They took up a firm but dignified attitude and presented the following remonstrance to the new Corporation :

” It being generally understood that it is in contemplation to discard the Douai Version of the Bible entirely from the Council schools, and to require that all the children shall use the Authorised Version of the Established Church, and shall, moreover, join in a common form of prayer at the beginning and end of school, the Catholic clergy of Liverpool beg most respectfully to state to the Council that they cannot conscientiously concur in such an arrangement, whereby the religious principles of the children attending the schools will be compromised ; and pray that the contemplated changes may not be adopted.”

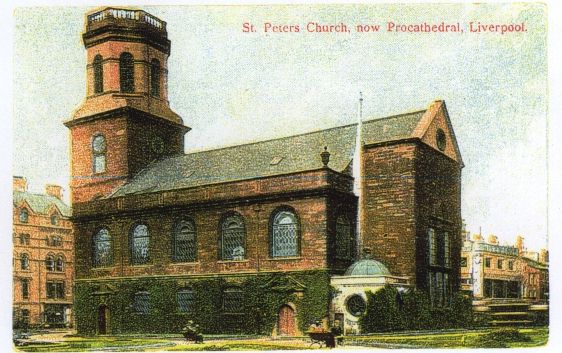

Then follow the signatures of the Rev. Dr. Youens (St. Nicholas ), Fathers Wilcock (St. Anthony’s), Thos. Fisher, O.S.B. (St. Mary’s), and Dale, O.S.B. (St. Peter’s).

Councillor Smith proposed that separate schools should be provided for the Catholics in poor districts. The debate which ensued was characterised by truculency and tolerance. Unitarianism and ” Popery “ were regarded as convertible terms by the Conservative leaders, and in insulting and contemptuous language the Catholic claim to be regarded as citizens was flouted and rejected. Why the Unitarian body should have been singled out for reproach was probably due to the fact that the leading Liberals, with few exceptions, belonged to that community, and distinguished themselves not only by their entire sympathy with the cause of religious toleration, but gave many practical tokens of sympathy with the Catholics of the town.

The Catholic children had no option but to withdraw from the Council schools, an action which gave intense satisfaction to the Tories, especially with regard to the North Corporation School. True to the course which had been mapped out beforehand, the Council schools were now turned into adjuncts of the Established Church, and all children in the Bevington Bush School were compelled to attend on Sundays and marched to the church service in St. Bartholomew’s, Naylor Street, unless the parents objected.” To mark his ” abhorrence “ of this policy, the Earl of Sefton sent a donation of twenty-five pounds to St. Anthony’s Schools, Scotland Road,[” Another kind of Town Councillor arose, who, with great pretension to religion, most irreligiously and unjustly, expelled from the public schools Catholic children by the hundreds.” St. Anthony’s Report, 1842.] and many other Liberals, including Sir Joshua Walmsley [ Mayor of Liverpool, 1839-40 ; afterwards M.P.] followed his example. The Catholic mind was finally made up. ” Schools of our own ! “ was the cry which resounded from every home as well as every pulpit. Thus the Tories of Liverpool may be styled the promoters of that magnificent series of Catholic schools which have sprung up in every quarter of Liverpool, to which came the teaching orders who lifted elementary education to the highest pinnacle of perfection. The bigoted Evangelicals did not anticipate such a result. Had they been far-seeing, instead of being blinded by rancour and partisanship, they would have seen that their policy would eventually bring about this result.

What would have happened had McNeill not driven the Liberals from power is now an interesting speculation. Every ward in Liverpool would have had its Council school, and under the disinterested management of a Liberal Education Committee most Catholic children would have been in attendance. Mixed schools are not looked upon with friendly eyes by Catholics, but the success of a six years experiment, and the poverty of the labouring classes, would, in all human probability, have prevented the erection of purely Catholic schools for a generation.

Where were the teachers to come from ? was the anxious query heard on all sides. The Government had made no provision for training teachers. Ireland came to the rescue, so far as the boys were concerned, and with the advent of the Irish Christian Brothers [The same work has been undertaken in Rome by the Irish Christian Brothers, at the express request of Pope Pius the Tenth. ] to St. Patrick s a new era of usefulness and charity was begun for that fine body of teachers. Later on they came to St. Anthony’s, St. Nicholas , St. Mary’s, and St. Vincent’s. Without payment or reward, save the voluntary offerings of the parents, these cultured men did a noble work for the poor children of their own race. To make them practical, earnest Catholics was their first aim ; to equip them for the battle of life was an easy matter for a body which had long distinguished itself by practical aims which have since disappeared from curriculums framed by more ambitious but less successful educationalists. For forty years they laboured in the town, and their departure under the pressure of the Act of 1870 caused widespread dissatisfaction.

To them belongs the distinction of founding the first evening continuation schools, in St. Patrick’s, during the year 1842, which were attended by one hundred and twenty Irish adults, anxious as most Irishmen have ever been for education. Such an impression was created by this experiment that Dr. Ullathorne, O.S.B., paid a special visit to St. Patrick’s to preach a sermon in its support. The Benedictines at St. Mary’s summoned a special meeting on December 16th, 1842, in the Grecian Hotel, to consider the sad plight of the great numbers of poor children in that district. They adopted a resolution regretting the decision of the Town Council, and resolved to issue an appeal to friends of education ” of all ” denominations to provide means of dealing with these “unfortunate children.” [Liverpool Albion.] Fathers Fisher, Wilkinson and Dale addressed a letter to the senior churchwarden of the Parish of Liverpool, Mr. W. Birkett, pointing out the condition of the poor children of St. Mary’s, and expressing the hope that the community would provide means for their instruction. The impertinent reply which followed illustrates the unfortunate tone and temper of the official Anglicans towards the Catholics of that day. Mr. Birkett began and ended by denying the right of the three Benedictines to claim the title of priests or be called “reverend,” as they had not been ordained in conformity with the laws of the Church of England. It became necessary to give this gentleman an elementary lesson in the doctrine of the Church whose self- appointed spokesman he had become, and Father Wilkinson was selected by his brethren to perform that duty. How well he performed the task may be gleaned from this crushing reply :

“With regard to my Orders, though I have not entered the ministry by making the declaration required by the rubrics of the Established Church, permit me, sir, to inform you, that the rubrics of that Church recognise the validity of my Orders ; and, if from a desire to have less labour and more pay, or any other equally creditable motive, I were to apostatize from the faith of my fathers, and embrace a creed in conformity with the laws of this realm, a Bishop of your Church would readily admit the validity of my Orders, and at once appoint me to a curacy. And now, as to my designating myself a Catholic clergyman, I am a humble member of the ancient faith, Catholic in every attribute, and in every sense, Catholic in all ages and in every nation ; Catholic by the received and admitted consent of mankind ; properly designated Catholic in history, geography, in the works of travellers, in the Senate, at the bar, in the public journals, in the drawing- room, and in every other department and locality, unless an exception be found in the vestry of Our Lady and St. Nicholas.”

Quoting the full title of the old parish church was the unkindest cut of all; devotion to Our Lady or St. Nicholas not being a prominent feature of the principles of the unfortunate recipient of this well-merited castigation.

The better educated members of the English Church heartily enjoyed Father Wilkinson s ready and apt reply. Church warden Birkett was snuffed out, and did not venture again into the fields of religious controversy.