CHAPTER XIV. This chapter takes us from 1843 to about 1846, and follows Josh and Lord Palmerston’s defeat at the 1841 election in Liverpool. It is quite unlike the previous five [political] chapters. It’s a tale of country life, and a picture of Josh as an agricultural pioneer. But it also throws in a series of major political figures as guests of Josh. It introduces Justus von Liebig(1803-1873), and James Muspratt as proof of Josh’s pioneering ways. Professor Liebig (1803-1873) was a German chemist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and was considered the founder of organic chemistry, and inventor of artificial fertiliser.

Richard Cobden was an Anti-Corn Law campaigner, and M.P, and shortly to be Josh’s next-door neighbour in Westbourne Terrace, in London. The Marquis of Saldanha was a Portuguese politician who was in exile following the Portuguese revolution of 1836, though he returned to become Prime Minister of Portugal in 1846. Sir Charles Wolseley (1769-1846), Josh’s neighbour in Staffordshire, was the 7th baronet of that name, and the family estate was in their hand for over a thousand years. The family finally losing it in 2014. Rather splendidly, Charles Wolsey was imprisoned for 18 months on sedition and conspiracy charges in 1820. William Cobbett (1763-1835) was a journalist, parliamentary reformer, and, towards the end of his life, a member of parliament. Cobbett spent two years in Newgate prison for treasonous libel in 1810.

As ever with Uncle Hugh, one is never entirely sure how much of this is embroidered, and what to take at face value, and what to be a little wary of. It could be him embellishing the story of his father, or it could be Josh himself adding to the tale, or mis-remembering. In any event, the only thing we can be sure of is William Cobbett not being at Ranton Abbey in 1846 because he had been dead for eleven years.

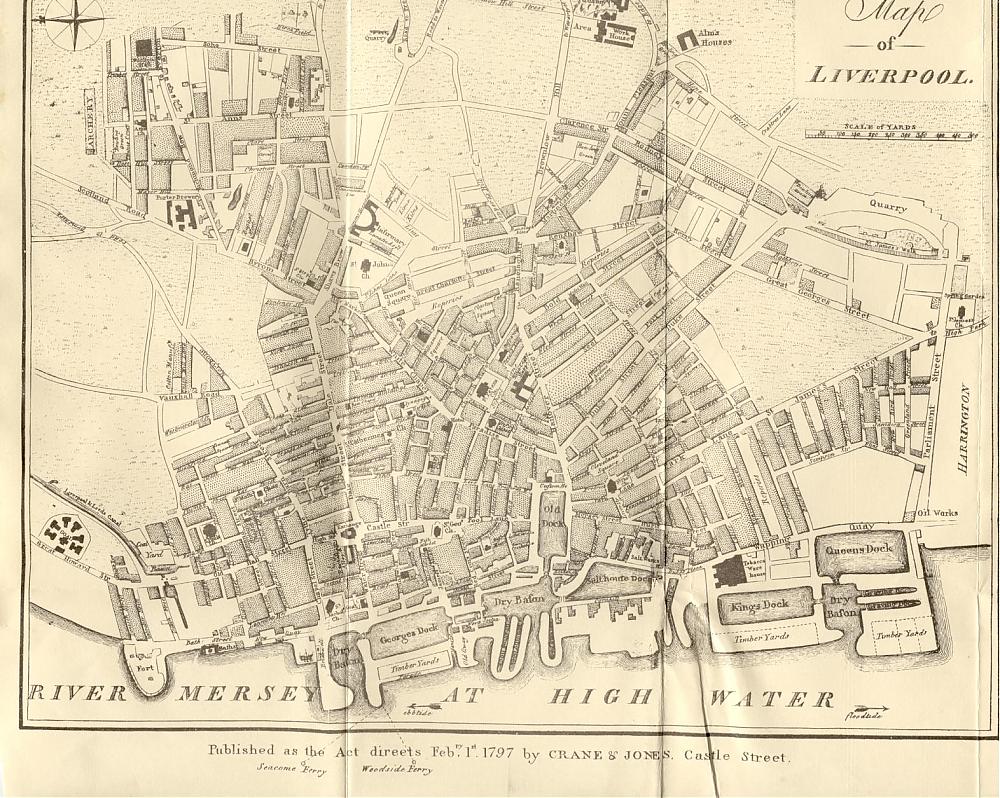

Sir Joshua deeply felt the loss of the Liverpool election, and he resolved to sever his connection with its municipality, and, without leaving business entirely, to enjoy a country life. In the year 1843 he carried out his plans, leaving Liverpool for Ranton Abbey, a property belonging to the then Earl of Lichfield, about seven miles from Stafford. This he rented, with the splendid shooting over several thousand acres.

With his accustomed energy he turned his attention to farming. ” Agriculture,” he says, ” was at a very low ebb in Staffordshire, and I resolved to mend matters if I could. Taking a few hundred acres of land into my own hands, I engaged a Scotch bailiff and two Scotch ploughmen. The tenants were a set of well-to-do farmers, whose brains grew a wonderful crop of prejudices. I got up an Association, the meetings being held at the Abbey, and argued with them, but it was hard work. Then I tried practical illustration. Turnips they asserted could not be grown on the land ; the soil was too heavy, and the fly took the young plants more than once in a season. I knew these objections to be valid, but thought I could overcome them. Taking a small piece of land, I manured it highly, forcing a crop of swedes early, so that it was ready for transplanting. As soon as the land was in a satisfactory state, and waiting a rainy term, I transplanted thirty-five acres. The result was a fine crop of turnips. I invited the yeomen and farmers to come and see the result. “

” They came, but they shook their heads over it. It was all very well for me, with a long purse, but it would not do for them. I proved to them by my account-books that the expense was not greater than the ordinary mode of culture, much hoeing out being saved. Still they shook their heads, and insisted turnips would not grow on this soil. “

” Another custom, dating from time immemorial, was to cut through the stiff clayey soil with a plough drawn by three, four, and sometimes five horses, placed one before the other in tandem fashion, led by a boy. At the Association meetings, I urged the loss of power consequent on the horses thus yoked dragging each the one behind him, and pointed out that two horses harnessed abreast would do more work, by giving all their strength to drawing the plough. A boy to lead them would also become unnecessary, and the expense of tilling the ground would thus be reduced one half or more. “

” Again the farmers shook their heads ; it was impossible, they said, for two horses to plough this stiff land. They declined to try the experiment ; the native ploughmen refused to enter my service, and drive my light Scotch ploughs with two horses yoked abreast. I was left in solitary grandeur to plough in my own fashion. The farmers would occasionally come round, and watch my two Scotch ploughmen at work in the fields. They shook their heads at sight of them, prognosticating I would soon come to ruin. A year passed, and I invited the farmers and the surrounding gentry to a ploughing- match offering a first, second, and third prize for the best work done within a certain time. On the trial- day ten teams were on the ground. A large concourse of spectators assembled, amongst whom were many leading agriculturists. Lord Talbot, Mr. Hartshome, Sir Charles Wolseley. It was a splendid day ; the house, the grounds, the fields were full of people. My two Scotch ploughmen stood behind their light ploughs, to each of which two horses were harnessed abreast. Every other plough present was drawn by a file of three, four, or five horses, the head of the foremost held by a boy. “

” When the ground was cleared the judges entered, and the first two prizes were adjudged to my two Scotch ploughmen, who had distanced all competitors in quality and quantity of work ; the third prize was awarded to an excellent ploughman who had been in my service but who had quitted it, and who that day drove three horses in tandem fashion. Thus were the advantages of the Gaelic system satisfactorily demonstrated. The next day Cobden and I were walking through some fields, when we came across the winner of the third prize driving a file of four horses. Cobden remonstrated with him in his mild clear manner, reminding him of yesterday’s result and explaining the reason of it. The man shook his head ‘ It’s always been the coostome of the country and we’re not going to alter it, ‘ he said. After awhile, however, the farmers one after another gave the experiment a trial, and finding the result worked better, and expense curtailed by half, the ‘coostome of the country ‘ was altered and finally done away with. “

” I was not, however, always in the right. At one of the meetings of the Yeomen’s Association, I dilated on the efficacy of deep trenching. When I thought I must have convinced the assembly by my arguments, I asked my hearers if I was not right. ‘ Ay, ay, Sir Joshua, right enow’ answered an old farmer, with a dryly humorous puckering up of the corners of his mouth, ‘ if ye want a field full of nettles.’ “

” According to my habit, I at once tried the experiment I had advocated on one of my own fields, the one that had produced the turnips. This field I had deeply trenched, not a nettle had ever been seen on it, but now the farmer’s words came true. It produced the finest crop of nettles ever seen in the country. Henceforth, the farmers never forgot to bring up the fact against me whenever I propounded one of my new-fangled ideas. ”

Sir Joshua’s interest in agricultural pursuits brought him at this time in contact with Professor Liebig. He read this eminent man’s work on agricultural chemistry, and was so impressed with the force of the reasoning displayed in it, that he wished practically to try the effect of restoring by chemical means the disturbed equilibrium of the soil, thus returning to it the exact amount of substance lost in the labour of production. “ With Mr. James Muspratt, of Liverpool, “ he says, ” a man well versed in chemistry, I entered into an arrangement with Professor Liebig to manufacture an article that would give back to land all that cropping had taken out of it. That soil would never decrease in fertility if the equivalent of its loss were restored to it, and that chemistry could exactly ascertain the loss and give back the restoring element, I deemed that Professor Liebig had satisfactorily proved. The courtesy, simplicity, and high sense of honour of the German professor, coupled with his genius, made me look back upon this partnership with him as a privilege, such as the failure of the enterprise could not lessen. “

” The ingredient was found too expensive for the returns, and after a fair trial, upon which was spent some thousands of pounds, the undertaking was relinquished. Professor Liebig being freed from all loss or responsibility. Though unsuccessful, I continued unshaken in the conviction that the professor was right, and that the experiment would prove successful in other hands. It was almost impossible that a small private undertaking could satisfactorily establish and work out a principle comprehensively proved by a man of genius, but that by its very nature must require vast appliances to carry out. Yet I always felt pride in the thought that Mr. Muspratt and I had been the first in England to endeavour to put into practice Professor Liebig’s self-evident theory. ”

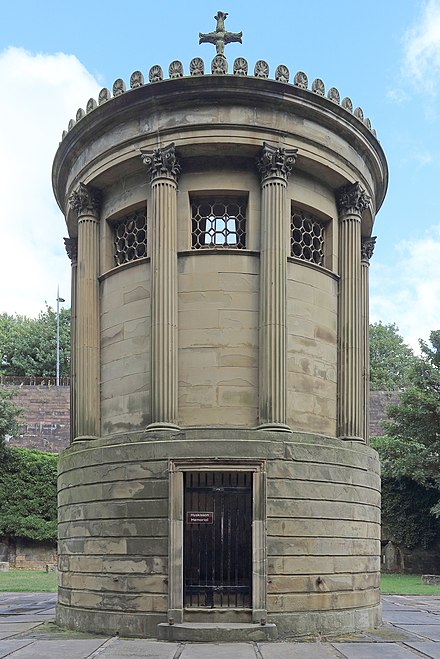

At Ranton, Sir Joshua delighted to gather around him his relatives and friends. The large house was always full of guests, among whom none was more frequent or welcome than Mr. Stephenson.

It was during one of his visits to Ranton that the portrait was painted that now hangs in the South Kensington Museum, and considered by the ‘ old man ‘ the best likeness ever taken of him. Another guest often to be met at Ranton was Sir Joshua’s neighbour, Sir Charles Wolseley, the friend of Cobbett. Of him. Sir Joshua says, ” Extreme in his political opinions. Sir Charles Wolseley advocated universal suffrage, annual Parliaments, paid representatives ; and yet he was loud in his denunciations of the manufacturing classes, whom he regarded as trenching upon the old county families, and whose interests he considered antagonistic to the landed interest. In the same breath that he portrayed the sufferings of the people, he would attack the idea of the repeal of the Corn Laws. Years before I knew him, his name had been struck off the Commission of the Peace, for instigating to sedition the mob at Chester, telling it in the course of an inflammatory speech that he had been present at the storming of the Bastille, and it was incomparably stronger than Chester Castle. He was the queerest compound of the aristocrat and democrat. His family pride was easily roused. “

” Once the Marquis of Anglesea, who was the principal owner of Cannock Chase, was negotiating with Sir Charles to buy from him the few hundred acres he held of that property. Before concluding the purchase, he requested the baronet to show his title-deeds, ‘ Go and tell the marquis that the Wolseleys held their estate before the Pagets were heard of. ’ said Sir Charles, and he at once broke off all negotiations. “

” Removal from the magistracy affected his spirits. His ways became eccentric ; he would often spend whole nights in his study, and the household would hear him in animated speech, addressing ‘Mr. Speaker,’ discussing the various political questions of the day, and with powerful eloquence describing the hardships of the people. Often Sir Charles and I went out shooting together, and not seldom we would lose ourselves in vehement discussion, for towards me the old baronet would step out of the sensitive and somewhat gloomy reserve he adopted towards others. The subject of railways was another constant topic between us. Sir Charles opposed them as vehemently as he opposed the repeal of the Corn Laws. No good could come out of either, and to every argument advanced in favour of quick locomotion, he would growl out, ‘ Why should we want to go quickly ? Between your Anti-Corn-Law League and your rail – ways, you’ll ruin England.’ ”

At Ranton, game was so plentiful that it was necessary to shoot every week during the season. Here the training of Kirkby Stephen stood Sir Joshua in good stead. Keenly enjoying the sport, the exercise, the glorious sense of freedom he had so relished in his boyhood, he never missed an available day. A pleasant friendly feeling existed between the tenants and the reformer who was always rousing them out of the comfortable, inert habits they had followed for generations. It was counted a grievance when shooting over a farm, if Sir Joshua did not go in to lunch with the owner. He and his head keeper, weighing some eighteen stone, and who was as active as he was weighty, following close at his master’s heels, were always welcome.

” During my stay,” he says, ” at the Abbey, where game was so plentiful as to require my utmost exertions to keep it under, I never had a claim from a farmer, never had to pay damages of any kind, or to prosecute a poacher. ”

Of his skill as a sportsman he gives the following example : ” I once laid a wager with a crack shot that I would fire at whatever passed before me in a narrow avenue, and that I would not miss one of the first fifty shots. I was accordingly posted in the centre of a small cover, on a rising ground, an under- keeper placed behind me to load a second gun. Beaters drove the wood before them, and the result was I successfully made sixty-four shots before missing one. ”

These were happy days at Ranton ; many were the shooting-parties that set out on bright autumn mornings, and for the most part the men that composed the group had, in one way or another, made their mark upon their age. ” On one occasion, “ says Sir Joshua, ” George Stephenson formed one of the party, and he carried a gun, and tramped sturdily along with the others. The ‘ old man ‘ seemed to enjoy the scene, but I noticed that during the day he never once fired a shot. The bag made was a large one, and at dinner Stephenson broke out into earnest remonstrances at the inhumanity he had witnessed that day, at the cruelty exhibited in such wholesale destruction of the wild creatures that enjoyed life so harmlessly. His protest had little effect in damping our ardour; we set out merrily next morning, but the ‘old man ‘ declined to accompany us. When we returned in the cool of the evening, we spied Stephenson on the other side of the lake, close to its edge, apparently beating the air with a bush held in each hand. On approaching we found he was engaged in a conflict with wasps, a hecatomb of which lay dead at his feet. His face and his hands were stung all over. At dinner, when the cloth was removed and servants were out of the room, the sportsmen had a good laugh at the ‘ old man.’ He did not escape scot-free from the sallies levelled against him for his wholesale destruction of wasps, but he returned the cross fire with quick retort, and defended himself well. ”

While enjoying rural sports and devoting much time and energy to farming pursuits it was evident this mode of life was nor enough to satisfy Sir Joshua’s energetic temperament, and that his mind was still pressing on towards the active political life that had once absorbed every other interest. ” Often when cover-shooting ” he tells us, ” a halt would be made at mid-day for lunch under the shade of some forest tree ; then political discussions would ensue between the sportsmen, and often interfere with the shooting. “

Sir Charles Wolseley would tell anecdotes of former friends. How, once he had invited Cobbett down to Wolseley Hall for a few weeks. There it was that the ‘ Legacy to Parsons ’ had been written, Cobbett dictating to his amanuensis in that pure idiomatic English of his, lashing himself up into a state of excitement, that every word might hit like the blow of a bludgeon. Weeks passed, Cobbett showed no signs of leaving. He occupied his leisure with gardening, a pursuit in which he delighted. Sir Charles at last, desiring himself to quit the Hall, intimated this to his old friend. Then the reason of Cobbett’s long stay came out. He, who at that time was influencing all England by his political writings and speeches, had not money wherewith to leave Wolseley Hall.

There was a walk on the farther side of the lake, which wound in and out amongst clumps of evergreens, and shaded by great trees. Here, in the Lady’s Walk, as it was called. Sir Joshua might often be found strolling about with such friends as Stephenson, Liebig, Cobden, the Marquis of Saldanha, William Cobbett, and others. With the three last he was ever sure to be deep in political discussions. They often urged him to return to public life. Invitations came from different boroughs to represent them in Parliament. ” My old friend Cobden was the most eager of all, “ says Sir Joshua, ” in pressing me to accept one of these. He would taunt me with abandoning the good cause. “ Some years were to elapse, however, before Sir Joshua would again seriously entertain the thought of entering Parliament.

In the meanwhile an episode occurred, that furnished many pleasant recollections to him in after life, viz. his journey to Spain with Mr. Stephenson.