CHAPTER XV. This is mostly 1845. George Hudson (1800-1871) was an English railway financier and politician who, because he controlled a significant part of the railway network in the 1840s, became known as “The Railway King”. Eventually in 1849, a series of enquiries launched by the railways he was chairman of, exposed his methods, and it was established that he was essentially running a Ponzi scheme paying dividends from capital. He had been elected M.P for Sunderland in 1845, and so was immune from arrest for debts. He become bankrupt in 1853, and after losing his Sunderland seat in 1859, he fled abroad to avoid arrest for debt, returning only when imprisonment for debt was abolished in 1870. General Narvaez was the Prime Minister of Spain. Sir Joseph Paxton was the head gardener at Chatsworth House, so close to Stephenson at Tapton House; he also designed the Crystal Palace, and was the M.P for Coventry for eleven years.

At this time the railway mania was at its height, and a company was formed to construct a line from Madrid to the Bay of Biscay. George Hudson was to be chairman. Sir Joshua travelled to Spain to inquire personally into details, and his report was unfavourable. This occasioned great discontent ; but it was only when George Stephenson offered to accompany him on a second voyage, and gratuitously give two months of his time, in order to survey the most difficult parts of the line, that Sir Joshua consented to a second journey. [This was the early autumn of 1845]

” Stephenson,” he writes, ” was a wonderful travelling companion. We travelled in an open barouche, and his keen eye was ever on the alert. Though abounding with difficulties, Stephenson asserted that they could be overcome, while at the same time he fully justified my refusal to deposit the caution- money. On reaching Madrid, Stephenson dictated one of those lucid reports he excelled in, setting forth the obstacles and consequent heavy cost, at the same time showing the importance of the line, and making stipulations in favour of the Anglo-Spanish Company. “

” Several interviews took place with General Narvaez, but all ended in a great show of politeness, great speeches, and nothing else. A bull-fight was organised in our honour ; but at last, to bring matters to a point, I notified that Mr. Stephenson and I would wait a week longer for the reply of the Government, and in the name of the English company refused to enter further into the scheme until our terms were agreed to. “

The week elapsed and still no answer came, so the travellers set their faces homewards. They took the more easterly direction and crossed the higher range of the Pyrenees, travelling, as they came, in the open barouche. ” The old man,” says Sir Joshua, ” usually sat with a map spread over his knees, and a pencil in his hand with which he marked down very accurately the villages as we passed. He enjoyed pointing out on the map the exact spot on which we were standing. “

” One day, after a weary ascent of several hours, during which Stephenson had marked out our route with pencil dots, he looked up and said : ‘ Walmsley, we’ll reach the summit in ten minutes now.’ ‘Nay, we’ve passed it already, we’re going down,’ I answered. “

” This reply was almost too much for the old man’s equanimity, always easily ruffled at contradiction. ‘You know nothing about it; it will take us ten minutes to reach the summit, I tell you,’ he said testily. After a short silence he threw down the map. ‘The map is all wrong,’ he growled. ‘ Nay, it was I who was wrong,’ he added, correcting himself a minute after. ‘ How did you know we were going down that time ? ‘ ‘While you were buried in your map I caught sight of a stream, and we were going down with it,’ I answered, laughing ; the old man joined in the laugh. ‘ Better look at nature than all the maps. You’ve beaten the old engineer for once,’ quoth he. “

” Another day the Spanish muleteers were urging their mules to a tremendous pace. ‘ No machinery could stand this pull,’ said Stephenson, and turning to our interpreter requested him to tell the driver to moderate his speed. The muleteers grinned in answer ; they evidently enjoyed what they took to be a token of the fright of the Englishmen, they therefore lashed and urged on their mules to go faster still. ‘ Another can play at the same game,’ said Stephenson, with the sense of fun that often made him seem but a boy in years ; and standing up he clapped his hands and he hallooed, evidently bent upon making the mules go faster and yet faster still. The muleteers were astonished ; the Englishmen after all were not frightened, and so they abated the speed and performed the rest of their journey at a reasonable trot.”

The travellers’ way now lay across France, and in this part of their journey occurred the two following incidents. ” We crossed on foot, “ says Sir Joshua, ” the chain-bridge suspended over the Dordogne. ‘Let us go over it again,’ said Stephenson, when we had reached the other side. Accordingly over it again we went, the ‘ old man ‘ walking very slowly with head bent down, as if he were listening to and pondering over every step he took. ‘ The bridge is unsafe, it will give way at the first heavy trial it meets with,’ he said, decisively, at last ‘We had better warn the authorities, your name will carry weight,’ I replied. We went to the mayor, we were politely received, and we related the object of our visit. The mayor shrugged his shoulders with polite incredulity ; he assured us that the engineer who had built the bridge was an able man. Stephenson urged his warning, supporting the interpreter’s words with gestures and rough diagrams drawn on the spot. Still the French official shrugged his shoulders, looked incredulous, and finally bowed us out. “

Only a few months later Stephenson’s warning came true. A regiment of soldiers crossed the bridge without breaking step, the faulty structure gave way, and scores of men in heavy marching order were hurled down into the eddies of the rapid river below, where many were drowned before means of rescue could reach them.

” Another day we passed by a French line in process of construction ; the navvies were digging and removing the soil in wheelbarrows. Stephenson remarked that they were doing their work slowly and untidily. ‘ Their posture is all wrong,’ he cried; jumping out of the carriage with the natural instinct that impelled him to be always giving or receiving instruction, he took up a spade, excavated the soil and filled a wheelbarrow in half the time it took any one of the men to do it. Then further to illustrate that in the posture of the body lies half the secret of its power, he laid hold of a hammer and mallet, and poising his figure, he threw it at an immense distance before him; challenging by gestures the workmen, who had now gathered round him, and were curiously watching him, to do the same, but they one and all failed to equal the feat. The interpreter explained the lesson to the navvies, and told them who their teacher was. ‘ Ste-vim-son ! ‘ the name went from mouth to mouth. The intelligent appreciative Frenchmen gathered close around him and broke into vociferous cheers, such as I thought could only proceed from British lungs, until the echoes rang around us on every side. “

” Pressing engagements were calling us home, and we journeyed continually day and night. The fatigue and irregular hours began to tell upon the old man’s health ; by the time we reached Paris, symptoms of severe indisposition had set in. I was anxious to get him home as soon as possible, but Stephenson consented to remain a day in Paris, to avail himself of the invitation of Mr. Brassey, Mr. Mackenzie, and others to a dinner given in his honour. The next morning a special train was ready to convey us to Havre ; Stephenson was very ill, but he persisted in travelling onwards. By the time we had reached Havre, unmistakable symptoms of pleurisy had declared themselves. I got him on board, and sent for a surgeon, who bled him profusely. There is little doubt this prompt action saved his life. On reaching London, next morning, I took him to the Arundel Hotel, Haymarket, where for six weeks he remained confined to his bed. I now became his nurse and sole attendant. “

” During the first part of the time, no one else was allowed near the sick man. Stephenson’s active temperament could ill brook the inaction to which he was now condemned, and he fretted against the precautions enjoined upon him. The activity of his mind remained wholly unimpaired by the sufferings of his body, and he kept pondering over his schemes. As soon as he was able, he insisted upon dictating aloud. I was his amanuensis, and was amazed at the clearness and vigour of his intellect, at the just views he entertained, not only on railway matters, but of the characters of public men. Remembering his lack of learning, the happy illustrations he used often surprised me, as well as the correctness of his style, that seldom needed alteration in word or phrase. “

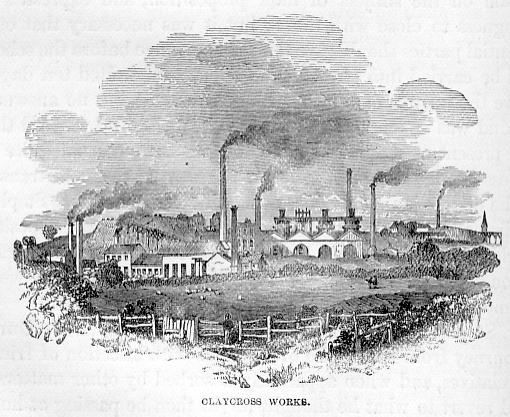

” What became of these papers I never could make out. Stephenson took possession of them, but they have not been given to the public. One treatise was devoted to the elaboration of a favourite scheme of his, for constructing a mineral or a goods train line of rail from the Derbyshire coal-fields to London. Coals and heavy goods alone were to be carried on this line. The idea originated with Mr. Charles Binns, secretary to Mr. Stephenson, and the present able manager of the Clay Cross Colliery.[Hugh neglects to mention that he was also Josh’s son-in-law, and his own brother-in-law] He had written a book upon the subject, that attracted much attention at the time. Stephenson had taken up the idea ; his arguments in its favour were strong, and in this treatise he enforced them with some eloquence. He pointed out how collisions would necessarily be avoided by the separation of the passenger and goods trains at the outset. That such an arrangement must ultimately be adopted, Stephenson was convinced ; and he advised that the construction of the goods train should go on simultaneously with that of the passenger line. I entered heartily into the plan, but in an evil hour it all fell to the ground. “

He had written a book upon the subject, that attracted much attention at the time. Stephenson had taken up the idea ; his arguments in its favour were strong, and in this treatise he enforced them with some eloquence. He pointed out how collisions would necessarily be avoided by the separation of the passenger and goods trains at the outset. That such an arrangement must ultimately be adopted, Stephenson was convinced ; and he advised that the construction of the goods train should go on simultaneously with that of the passenger line. I entered heartily into the plan, but in an evil hour it all fell to the ground. “

” Another paper, “ says Sir Joshua, ” dictated by Stephenson during his illness was devoted to the arguing out of his original proposal, that Government should construct and hold the Grand Trunk lines of rail through the country. He pointed out all the jobbery that would have been avoided had this plan been adopted from the first, and he fearlessly showed up the deplorable mismanagement that had occurred in railway direction. He painted George Hudson’s portrait with such keen discriminating touches, that I was amazed at the fidelity and delicacy of the delineation. At this time the railway king was at the zenith of his power, courted and toadied by the aristocracy. Stephenson predicted his speedy downfall No one appreciated more than he did the pluck, the strong will, and business capacity of Mr. Hudson ; qualities that had lifted him from his small draper’s shop in York to the place of arbiter of the fortunes of millions in England ; but that no eminence can long be held by unprincipled means, was a tenet too firmly held by the ‘ old man ‘ to allow him to be swayed or blinded by the railway king’s position. Another treatise he dictated to me was in vehement opposition to the proposed atmospheric railway. He was very positive in his condemnation of the scheme. It is told that one day, when a nobleman, a zealous advocate of atmospheric railways, said to him : ‘ Mr. Stephenson, you are a very able man, but you are not strong enough for the atmospheric system.’ With characteristic fierceness, the ‘ old man ‘ seized him by the collar and expelled him from the house. Those papers also contained some valuable observations on the steam-plough, and the heaving up of coal by machinery, in both of which experiments Stephenson believed. “

” When Stephenson’s report was laid before the board of directors, the scheme for an Anglo-Spanish railway was abandoned, and the line of conduct I had adopted in the first instance was justified. The subscribed capital, minus incurred expenses, was ultimately returned to the shareholders. So persuaded however, was Mr. Stephenson that the railway was practicable, and that when achieved it would prove of the highest importance to the Spanish nation, that he again tendered his services gratuitously as consulting engineer to the Spanish Government, should it resolve upon constructing the line during his lifetime. ”

A few more details, gathered from the notes before us, and the record of Sir Joshua’s and Mr. Stephenson’s friendship closes for ever. In them we see the latter at Tapton House, surrounded by his dogs, his horses, and his cows. His enjoyment of country life remained to the end, keen as in his boyhood. ” He was very proud of his vines, melons, and pine-apples,” says Sir Joshua, ” in the cultivation of which he would only admit Sir Joseph Paxton for rival.” Before this hale and vigorous old age many years seemed still to be stretching.

In January, 1848, Mr. Stephenson married for the third time. The marriage was contracted without Mr. Robert Stephenson’s knowledge, and it caused some ill-feeling between him and his father. Sir Joshua Walmsley became the mediator between the two. Letters before us, of a nature too delicate and private for publication, show the tact and zeal with which he pursued his self-imposed task. No one understood better than he the strong affection that bound the father and son. Mr. Robert Stephenson has said that he never had but two loves in his life, his wife and his father; and this only son was the chief pride of the old man’s heart

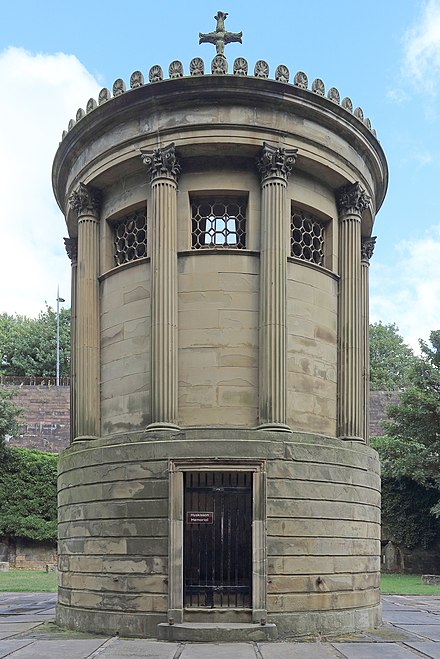

Suddenly, on the 10th of August of this same year [1848], Stephenson died. A chest complaint carried him off at the age of sixty-eight, before any of the many sources of interest and enjoyment of life had begun to fail him. His son was with him— his faithful and tender nurse to the last during this illness.

Two days before the great engineer’s death came the news that the House of Lords had passed the bill for the railway from Ambergate to Manchester. Stephenson gave a feeble cheer at the tidings. He had long struggled to obtain the passing of this Act.

On Thursday, the 15th, Mr. Stephenson was buried in Trinity churchyard, Chesterfield. Mr. Robert Stephenson wrote to Sir Joshua : ” I am desirous that the funeral should be as private as possible, attended only by a few of his pupils, who like myself have been dependent upon him for our professional success. “ There was, therefore, no large gathering of mourners at the house, but the mayor and corporation of Chesterfield met the cortege on its way. A file of carriages and a train of three hundred persons followed the hearse, that was bearing to its last resting- place the body of one revered by all for the greatness of his services, and very dear to those who had known him intimately. ” He ought to be lying in Westminster Abbey, and not in a country churchyard, “ Sir Joshua often said.