This post seems to be getting rather more interest, and it is probably time to re-visit and revise it. It was published almost two years ago at the start of the whole thing. The original information came from a website called http://www.researchers.plus.com which is now, I think, rather moribund. Some of the information was a useful spur, some was a distraction, and some just needs more verification before it can be taken as solid fact. So this is a recent update and addition to the original from November 2016.

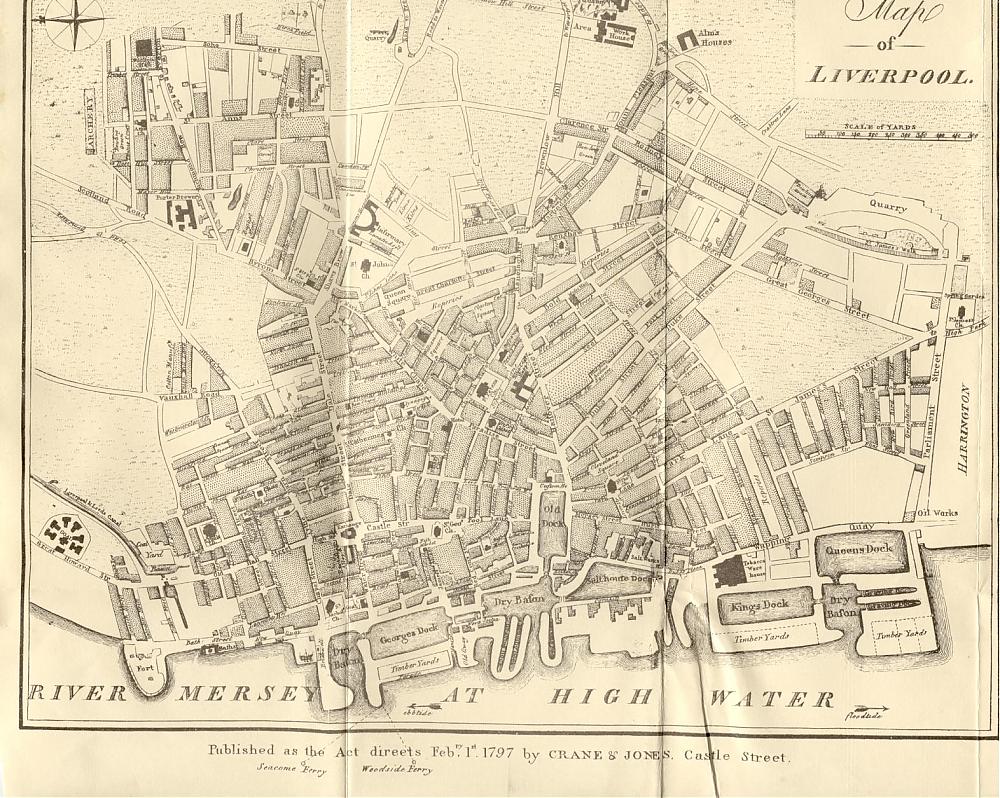

So lets start with some basics. Joshua Walmsley married Adeline Mulleneux at St. James’ church in Toxteth on the 24th June 1815, six days after the battle of Waterloo. They had eight children, five girls and three boys.

- Elizabeth Walmsley b. 1817 – d. bef 1861

- Joshua Walmsley II b. 1819 – d. 1872

- Hugh Mulleneux Walmsley b. 1822 – d. 1881

- Adeline Walmsley b 1824 – d. 1842 – died aged 18.

- James Mulleneux Walmsley b. 1826 – d. 1867

- Emily Walmsley b. 1830 – 1919

- Mary Walmsley b. 1832 – d. bef.1851

- Adah Walmsley b. 1839 – 1876

The eldest child, Elizabeth married Charles Binns (1815 – 1887) in 1839. Charles was the son of Jonathan Binns, a Liverpool-born land agent and surveyor living in Lancaster. The Binns were a fairly prominent Quaker family; Jonathan Binns was a Poor Law commissioner who did a survey of Ireland in 1835 and 1836 which was both insightful, and rather heart-breaking. His father Dr Jonathan Binns was an early slavery abolitionist, and later headmaster of the Quaker boarding school at Ackworth in Yorkshire. Charles was George Stephenson’s private secretary, and later manager of the coal mines and ironworks at Clay Cross, Derbyshire, which had been established by George Stephenson, and of which Sir Joshua Walmsley was a co-owner and director. The family connection with Clay Cross continued for almost a hundred years. Charles and Elizabeth had four children, all girls; but Elizabeth seems to have died in the early 1850s. Charles remarried in 1871, and died in 1887. Emily Rachel Binns, Elizabeth and Charles’s youngest daughter married Samuel Rickman. Her first cousin Adah Russell, the daughter of Adah Williams [neé Walmsley] had married Charles Russell who was a prominent London solicitor, the son of the Lord Chief Justice, and the brother and uncle of two more Law Lords.

Much less is known about Sir Joshua’s eldest son Joshua Walmsley II (1819-1872). He seems to have joined the Army, attaining the rank of captain. He lived in southern Africa for many years and served as a border agent in Natal on the Zulu frontier. He crops up as a peripheral character in some of the accounts of the British dealings with the Zulus, particularly the Battle of Ndondakasuka – 1856, and he employed a very strange man called John Dunn as a translator in his dealings with the Zulus. In the aftermath of the battle, the young Zulu King Cetshwayo was so impressed by the equally youthful John Dunn’s conduct in the midst of Zulu internecine clan bloodletting, that he invited the Scot [Dunn] to become his secretary and diplomatic adviser. Cetshwayo rewarded Dunn with traditional gifts of a chieftainship, land, cattle and two Zulu virgins to be his wives. This last gift greatly upset Catherine, Dunn’s 15-year-old mixed-race wife. But it did not deter him from taking at least another 46 Zulu wives. By some unofficial accounts, Dunn fathered 131 children by 65 wives, though his will records only 49 wives and 117 offspring. Catherine retained the title of “Great Wife”, giving her the privilege of being the only wife allowed to enter his presence unannounced. How, and why he [Joshua] went to South Africa is still unknown, but the Army, and then colonial service, was probably regarded as a step up from trade. It may well also have helped escape the shadow of his father.

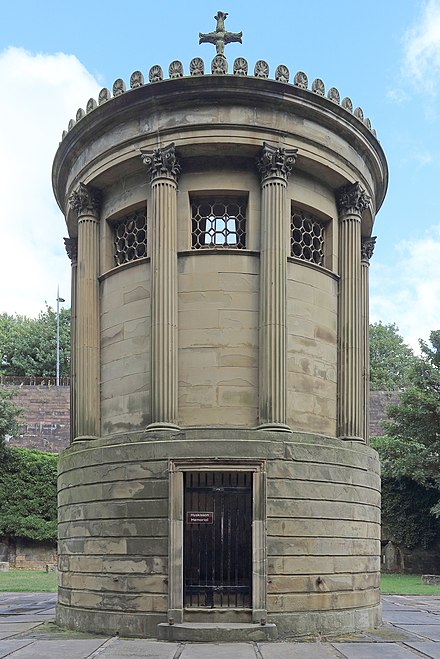

He was buried at St Mary’s, Edge Hill [the same cemetery as his brothers, sisters, parents, and a large numbers of the Mulleneux family including his maternal grandparents] in Liverpool on 14th December 1872, having died at “Chantilly, Zulu Frontier, in South Africa” on 20th April the same year. He left his widow £2,000, so a fairly respectable amount of money.

Hugh Mulleneux Walmsley (1822-1882) also joined the Army. He served time with the 25th Bengal Native Infantry, and then volunteered to join the Bashi Bazouks, which was a semi-mercenary Ottoman force – the name literally translates as “crazy-heads”. The Bashi Bazouks mainly recruited Albanians, Bulgarians, and Kurds, and had a reputation for bravery, savagery and indiscipline. They weren’t salaried and relied on looting for pay. In due course he rose to the Ottoman rank of colonel, and described himself as such in the 1871 census ” Ret. Colonel Ottoman Ind. Corps, late 65th Foot [ie. a British regiment]”. So it doesn’t appear to be something he was ashamed of. On his return to England sometime in the 1850s he started to write. The books included several describing his own military service, a biography of his late father and also some adventure novels including The Ruined Cities of Zulu Land based on Josh junior’s travels. He married Angelina Skey (b 1826) in 1870 and moved to Hampshire close to his parents. He too was buried at St Mary’s, Edge Hill in Liverpool, along with large numbers of the family, on 12th December 1881. His burial record states he died at ” St. André “ in France, which could be any one of thirty-plus places.

The next child is another Adeline Walmsley (1824-1842), this is the second daughter born in 1824, in Liverpool. All the children are named either after their parents or grandparents, or other family members. Elizabeth is easy, named after both their mothers, this Adeline was named after her own mother. Joshua II, Hugh, and James are named after father, grandfather, and uncle respectively. There is very little to be known about this Adeline, she appears on the 1841 census when the family have moved out of Liverpool to Wavertree Hall, then in a country village outside the city. Her death is recorded in the autumn of 1842 in Staffordshire, just as the family had moved to Ranton Hall in Staffordshire

James Mulleneux Walmsley (1826-1867), by contrast to his brothers became a civil engineer.James aged 15 is shown at home at Wavertree Hall in 1841. In the 1851 census, he was lodging and working in Derbyshire. He was at Egstow House, very close to Clay Cross, suggesting he was involved with the family mining and ironworks business. His brother-in-law Charles Binns [Elizabeth’s husband] and family were already there living at Clay Cross Hall about a mile away. Ten years later, he is living with his parents, and two youngest sisters at Wolverton Park, in Hampshire. He died on December 6th, 1867 aged 41 and was buried on December 12th with his sisters [Adeline, and Mary] at St Mary’s, Edge Hill. He died in Torquay. James was unmarried, and his addresses for probate were given as 101 Westbourne Terrace, and also Wolverton Park, Hampshire, both his father’s houses, and “latterly of Torquay, Devon”. Probate was granted to his father’s executors because Sir Josh was the “Universal Legatee”. It wasn’t granted until 1874, about three years after Sir Josh’s death in 1871. James left a fairly respectable £2,000.

Emily (1830 -1919) the third daughter, in contrast to James lived until almost 90, and was a widow for almost forty years. She was the second wife of William Ballantyne Hodgson (1815-1880), who was a Scottish educational reformer and political economist, even though he spent more of his time working in England. In 1839, Hodgson was employed at the new Mechanics’ Institution (later Liverpool Institute) just before Sir Joshua became mayor, and went on to become its Principal. He married Emily in 1863 and they mostly lived in London till Hodgson was appointed the first Professor of Political Economy in Edinburgh University in 1871. After he died in 1880, Emily stayed on in Edinburgh with their children, it’s not entirely sure how many. The Dictionary of National Biography says two sons and two daughters, however I can only find Alexander Ireland Hodgson (1874-1958) and Lucy Walmsley Hodgson (1867-1931)

The youngest daughter Adah (b 1839) married a Welsh banker, William Williams, in 1866. They went to live in Merionethshire and had at least two daughters. Adah possibly died as early as 1876. Their daughter Adah Adeline Walmsley Williams (1867–1959) married Charles Russell in 1889. Charles Russell was a solicitor who worked for the Marquis of Queensbury during his libel case with Oscar Wilde. Charles Russell’s father was Lord Chief Justice between 1894 and 1900. The first Catholic to hold the office for centuries. Charles Russell was made a baronet in 1916, and then got the K.C.V.O in 1921, so I suppose that technically he was Sir Sir Charles, and Adah was Lady Russell twice over. Charles’ baronetcy was inherited by their nephew Alec Russell because he [Charles] had arranged a special remainder allowing it to be inherited by male heirs of his father. A nicely lawyerly touch given that he and Adah had a daughter, and by the time he was made a baronet it was extremely unlikely they would have a son. Adah was 49 at the time. But even better, because their daughter Monica married her cousin Alec, she, Monica, became Lady Russell as well because her husband inherited her father’s baronetcy

Gwendoline Walmsley Williams, her sister, married Denis Kane in 1897. He was an Army officer; the wedding was ” hastened owing to Mr. Kane’s being ordered to join his regiment at once in the Tirah Field Force on the Indian frontier. ” He survived that but died about a year later playing polo in India.