CHAPTER VIII. This chapter takes us through the council elections in 1835 up to the end of 1836. Again, no mention of family, even though by this stage there were five children. Three teenagers, a ten-year old, and a six-year old, with one more daughter to come. The Municipal Reform Bill had followed the 1832 Reform Bill which extended the franchise, and reformed constituencies, and had re-organised local government. In Liverpool’s case, it increased the electorate to all rate-payers changing the corporation from a self-selected group of freemen.

In December, 1835, municipal affairs were creating much stir in Liverpool. The Municipal Reform Bill had become law in the preceding September, sweeping away all close corporations and restoring to the citizens their ancient municipal rights. The Corporation of Liverpool, which had usurped these privileges since the twenty-sixth year of the reign of Elizabeth [1586 – two hundred and fifty years] , had been composed of forty-one self-elected members, altogether irresponsible in their management of local transactions. Freemen alone had the right of voting for the mayor and electing the member to represent the borough in Parliament. Accordingly, the Liverpool corporation strenuously opposed the passage of the Municipal Reform Bill. It petitioned Parliament to be heard in its defence against the report of the commissioners on the state of municipal bodies, but the Legislature paid no heed to its prayer and made no exemption in favour of the borough. Henceforth every ratepayer who had resided three years in the town was entitled to have a voice in its government.

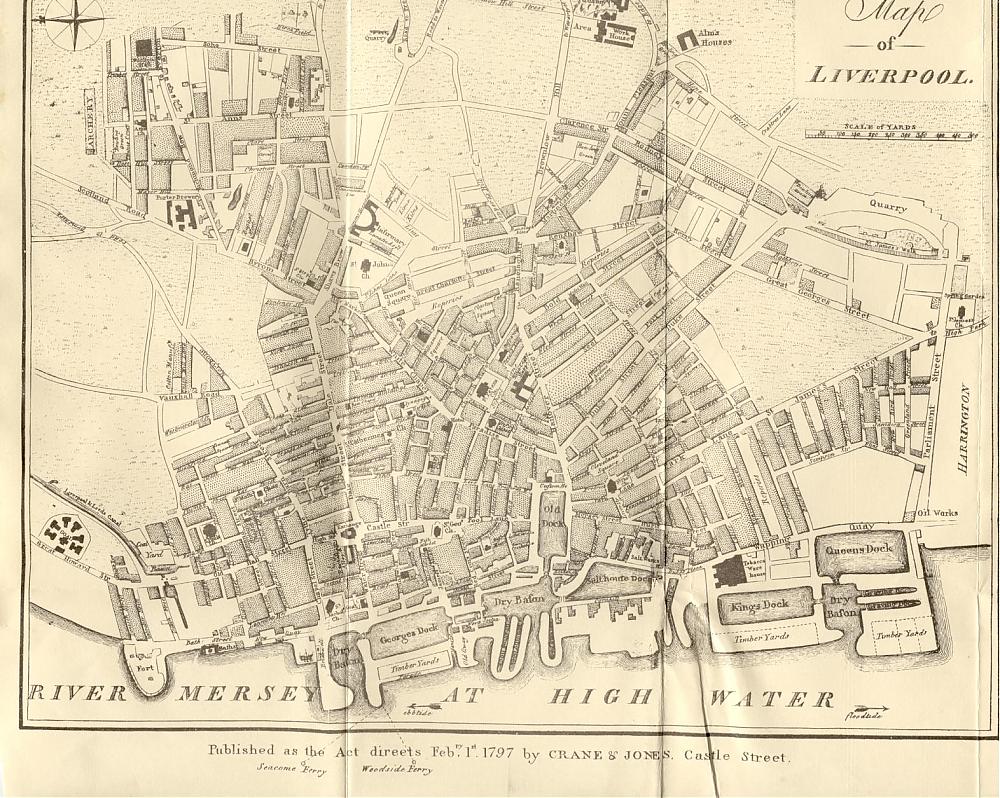

The town itself was divided into sixteen wards, each ward to elect three councillors. Mr. Walmsley was invited to stand for Castle Street, and in his address to the electors he stated his tenets. ” The principles I shall advocate at the board will be based upon my earnest conviction that civil and religious liberty is most consistent with Christianity, and I hold that the interests of mankind are best advanced by the man whose conduct in social life shows him to be guided by the rule of doing unto others as he would they should do to him.” ” My support,” he continued, ” shall be given to measures having for object the distribution of equal privileges, the reduction of local burdens, the extension of education, and the employment of the corporation funds in a way that may best conduce to the improvement of the town.”

The election took place amid considerable excitement. The first return showed the Liberals at the head of the poll in Castle Street Ward, Mr. Walmsley heading the list. At half-past four, Mr. James Branker announced the result. Forty-three out of forty-eight councillors were Liberals. Henceforth Mr. Walmsley’s position was no longer merely that of the private citizen amassing wealth for himself and family — he was a member of a body on whom devolved the duty of legislating for the general good. As member of the watch committee, he noticed that though the ” Old Charlies “ had nominally disappeared, and had been replaced by one hundred and thirty watchmen with superintendents and inspectors, they were for the most part aged and inefficient, nor were they worked on the crime-preventive principle.

The plan laid before the council for the new police was modelled on Sir Robert Peel’s organisation of that of the metropolis. Let us leave Mr. Walmsley to speak for himself as to the manner in which he took the lead in this.

” I resolved to arouse public attention and stimulate public opinion to the pitch necessary for vigorous and decisive action. To do this I set about exploring through all their ramifications the dens of crime in the borough. My position enabled me to command the aid necessary for this purpose. It was a loathsome task to undertake, but I pursued it to the end, hunting vice through all its windings till I traced it to its nurseries, and it was often at the risk of personal danger that I made this survey. Many a time, too, have I felt a sickening recoil as the mournful and appalling spectacle unrolled itself before me. I saw for myself how gradual and easy was the descent to crime, how bright-faced boys became trained thieves in time. I saw with what facility stolen property could be converted into money. I entered mean obscure shops in by-streets and lanes, where rags and secondhand dresses were exhibited in the windows, and in the back rooms of which glittered the booty the receivers had bought from thieves. I went down into damp, dark cellars, unfit for human habitations, where men and women lived huddled together. These were necessarily the headquarters of disease and crime. Step by step, I collected my information, and accumulated proofs of my assertions ; then I embodied the whole in writing, and laid it before the municipal board. “

” When I read my report on the state of crime in Liverpool, the council refused to believe it. The amount of vice in the town, I calculated, cost society upwards of seven hundred thousand pounds to maintain. There were more than two thousand notorious male thieves, besides twelve hundred boys under fifteen. There were several hundred receivers of stolen goods. Some laughed at the report, deeming such a state of things impossible, others contended that it must be founded on mistaken statistics. The matter might have dropped here, but I demanded a committee of inquiry, and it was granted. The result was such as I had anticipated. I had understated rather than overstated my case. There was no over- colouring in the picture.”

” A discussion ensued in the town council as to whether the report should be published. Some feared that it would fix a stigma upon Liverpool ; others, on the contrary, maintained that it would redound to its credit, as being the first town that had boldly confronted the evil It was finally decided that five hundred copies should be printed. The subject was taken up and was much talked about, not only in Liverpool, but in other places, and the statements it contained appeared so incredible that again doubt was thrown upon its veracity.”

An eminent member of the British Association, taking a decided stand against it, afforded Mr. Walmsley the opportunity he sought. He wished to secure publicity to his report ; to show that crime is for the most part the result of wretchedness and ignorance, from whose taint many might be rescued if a proper system of police existed. At the following year’s meeting of the Association in Liverpool, he read a paper in which again he discussed the state of crime in the town. He dwelt upon the pernicious effects of cellars crowded with human beings, and called attention to the thousands of such cellars that existed in Liverpool. Evidence was there to support his statements. It is sufficient to chronicle as one result of his efforts in this direction, that an Act of Parliament was passed, and the cellars of Liverpool were condemned.

” I was now appointed,” says Mr. Walmsley, “ chairman of the Watch Committee. Fifty-three only of the old watchmen were retained. Two hundred and eighty new men were added to the force, under the orders of one head-constable, responsible for the conduct of the whole body, and having under him a staff of superintendents and inspectors. Mr. James Michael Whitty, late superintendent of the night watch, was appointed head-constable. His tact and experience greatly aided me in framing a code of rules and regulations that have stood the test of practice. To give the new force a sense of the dignity of its office was my first care. Superannuated and infirm men were no longer to fill its ranks. Each member of it was to be a picked man, bearing a high character before being enrolled. It was trained to be preventive so far as was involved in its being directed to watch closely all that had a tendency to corrupt morals. It took me three years to mature a code of regulations, and personally to inspect the carrying out of its details. Many hours of the day, and frequently large portions of the night, I devoted to the task.”

From Mr. Whitty’s own lips we have noted down the following testimony of Mr. Walmsley’s services in the organisation of the police. “ I had practically studied the question, and was thoroughly acquainted with what ought to be done. Mr. Walmsley knew this, and listened to me with great deference, soon mastering all details as thoroughly as I did ; so that when the new police was to be formed he became chairman of the watch committee. No abler man ever presided. He was indefatigable, and used to go his rounds with me night and day, taking great interest in the efficiency and discipline of the force. There was a strong opposition on the part of the mob, but gradually we overcame all difficulties. The police of Liverpool was established. It was regulated for the most part on the same principle as the London constabulary, but fewer men did the work better. Other towns sent down inspectors to obtain information, but very few succeeded in mastering its details. The Liverpool police force was the first established out of London, and Mr. Walmsley mainly contributed to this.”

One incident will show how Mr. Walmsley met the opposition of those hostile to the new system. No attempt to reform the morals and condition of the lower classes can ever be effectual, that does not include the surveillance of public-houses. The new police force was authorised to enforce very stringent regulations. The enemies of the reform council declared this an insult to the trade, and an infraction of justice by the municipality. The publicans announced their intention to convene a meeting to protest against the tyranny of the new police, and to censure the watch committee.

Before the day appointed for the meeting, at Mr. Walmsley’s invitation, a deputation of publicans waited upon him. He listened to the tale of their supposed grievances. In his answer he at once touched the right chord, appealing to their sense of right. In the words of the publican who related the interview : “Mr. Walmsley showed us that there ought to be no divided interests in a town, that each class of civilised society depends on the other. He pointed out the great injury done to morals by disorderly public- houses, making us ashamed of our opposition to the police, and changing it into a desire to co-operate with it, in putting down customs that were a disgrace to the trade.” The deputation left with a sense that they had been practised upon by those who persuaded them that publicans were specially oppressed.

When the day appointed for the meeting came round to publicly protest against the new police force, to censure its organiser, the purport of the assembly was changed. The few promoters who spoke only did so to withdraw their names. Hearty praise was given to Mr. Walmsley, and before separating, the meeting passed a resolution ” that all publicans would henceforth join to help the police in the fulfilment of its duties.”

The diminution of crime in Liverpool at the close of the first year was the best answer that could be made to the attacks on the police. The learned Recorder, on the occasion of the quarter sessions, October, 1836, congratulated the jury upon the present calendar not containing a moiety of the cases set down for trial that did that of the previous year.

He ascribed this result to the new police force, organised in the town and trained on the principle of prevention. The grand jury made a presentment recording its high approval of the new system, of the way each man brought before the jury had given evidence, and the activity displayed in the detection and suppression of crime.