Liverpool had expanded hugely over the course of the eighteenth century, from a small fishing town with a population of 5,714 in 1700, to a 1,400% increase of population to 77,708 in 1801. The population more than doubled again by 1831 to 165,221. The vast majority was immigration from Ireland. The pressures this created on the need for housing, schools, and churches form a rather murky undertone to almost everything that happens in Liverpool, and particularly the politics. There are other strands as well, the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the Corn Laws in 1815, a succession of poor Irish harvests in the 1820’s and 1830’s, the fight for Catholic emancipation leading to the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, and the fight for Parliamentary Reform.

The following is largely extracted from Thomas Burke’s ” Catholic History of Liverpool,” Liverpool : C. Tinling & Co., Ltd., Printers, 53, Victoria Street. 1910. The wording in brackets is from footnotes in the original.

” The opening year of the nineteenth century witnessed a large influx of poor Irish people into Liverpool. One writer attributed the immigration to the passage into law of the Act of Union [Brook’s History of Liverpool.] which abolished the Irish Houses of Parliament, and provided for the future government of Ireland from Westminster. It is difficult to see how such an Act was directly responsible for sending the Irish of 1801 in large numbers to Liverpool, though it is certain that the result which ensued therefrom created the Irish Liverpool of a later date.

In the year 1821, the Catholic population, estimated by the numbers attending Mass on the Sunday mornings, was 12,000, as compared with a total seating accommodation of 56,200 in all the Anglican and Dissenting places of worship in the town. From a census taken in this same year we learn that the total number of houses occupied were 19,007, the average number of dwellers therein amounting to 5.84.

A distinguished Liverpool Irishman, [Henry Smithers, in Liverpool, Its Commerce, Statistics, and Institutions: With a History of the Cotton Trade, T. Kaye, 1825] calculated that ten years earlier (1811) there were 21,359 Catholics living inside the town boundaries. As corroborating this opinion, a priest attached to St. Nicholas speaking at a public meeting in the schools in 1830, declared that the Catholics numbered not less than one-third or one-fourth of the entire population, [165,221 in 1831] and called special attention to the definitely ascertained fact that in the course of twenty-three years the number of Catholic baptisms had increased 340 per cent. [Liverpool Mercury, 21st May, 1830.]

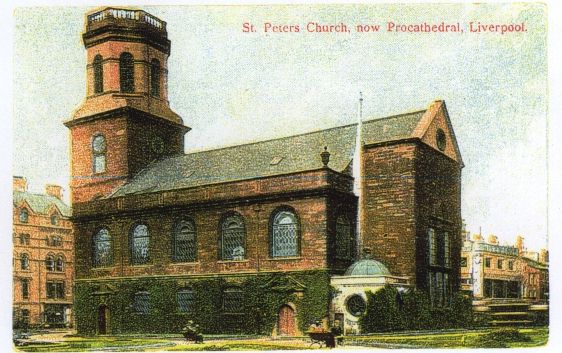

More churches were needed. The next extension of church accommodation took place at St. Peter’s, Seel Street, the extended church being opened on November 27, 1817.

More churches were needed. The next extension of church accommodation took place at St. Peter’s, Seel Street, the extended church being opened on November 27, 1817.

In 1822, another influx of Irish immigrants arrived in the town, due to the severity of Irish landowners, who demanded their pound of flesh notwithstanding the generally depressed condition of Irish agriculture.

The newspapers record the sequel in these words. ” Crowds of indigent poor sought relief at the workhouse in Cumberland Street, and at the parish church of St. Peter’s, Church Street.” It would be an interesting item of historical value could we calculate the heavy cost to Liverpool ratepayers of Irish misgovernment, and a no less interesting speculation would be the progress of Catholicism in Liverpool had Pitt failed in carrying into law the ill-fated Act of Union. This second exodus from Ireland to Liverpool must have been very considerable, as a local historian* tells us that around the Exchange not fifteen in a hundred were natives of the town owing to the numbers of poor Irish arriving daily. This immense mass of Catholics around the Tithebarn Street and Vauxhall Road area, entailed serious consequences social and economic to the town which have not wholly disappeared to this hour (1910), and brought about the erection of further chapels and schools, but for which the citizens of Liverpool had been brought face to face with insoluble problems of crime and lawlessness. Liverpool has failed entirely to realise its debt to the devoted Catholic clergy and the energetic Catholic laymen who saved the situation to some extent both in the twenties and the terrible years which were soon to follow.

This Irish congestion had a curious sequel if we are to credit the statement that when the “cabbage patches “ which lined ” the road to Ormskirk,” had to give way to much needed sites for dwelling houses, the new street was called Marie-la-bonne, modified to Marybone, at the request of the Catholics ” who began to occupy the houses erected.”! Agricultural land now assumed a high value as ” eligible “ building sites, and brought in its train as a logical result the awful problem of housing the poor which perplexes local and imperial statesmen ignorant of the one method of solving the difficulty.

St. Mary’s Chapel, just sixty-six feet long and forty-eight broad was sorely taxed to find room for the thousands who sought to hear Mass therein…… A similar state of affairs existed at the South end of the town. Seel Street Chapel was utterly unable to cope with the congested Irish population living in the streets off Park Lane and St. James Street, and a lay committee took in hand the erection of a new church to supply the spiritual needs of this Irish colony.

The dedication of the church leaves no doubt as to the nationality of the poor for whom it was founded and quite a thrill of enthusiasm swept over the Irish population at the announcement that the Park Place Church was to be placed under the protection of the Apostle of Ireland. [Strong opposition was offered by the Protestant body to the erection, on the ground that there was plenty of accommodation already.] Touched by the needs of the Irish poor many of the leading Liberals gave substantial assistance towards the undertaking, and the poor contributed their mite generously and whole heartedly. The English Catholics of the town were generous to a degree and on the 17th of March, 1821, not many months after the project had been conceived, the foundation stone was laid amidst scenes of jubilation, probably never equalled since that memorable day.

St. Patrick’s feast occurred on a Saturday that year, not the most suitable day for public rejoicings or processions, but the day mattered not, the heart of Catholic and Irish Liverpool was touched in its tenderest part, and a great procession was the result. Those were the days of great faith. Consequently the day was opened by the Irish Society attending Mass at St. Mary’s, a compliment to the parent church as well as a thanksgiving to God, and then reforming, the procession wended its way to St. Anthony’s, where the second half of the procession had also heard Mass at an early hour. Led by several carriages in which were seated the rector of St. Nicholas, Father Penswick, Father Dennet, of Aughton, and the preacher at the ceremony, Father Kirwan, St. Michan’s, Dublin, the monstre procession moved off on its long march to Park Place. Then followed the Irish Societies, wearing their regalia, bearing banners and flags, and accompanied by numerous brass and fife bands, including the Hibernian Society, Benevolent Hibernian Society, Hibernian Mechanical Society, Benevolent Society of St. Patrick, Amicable Society of St. Patrick, Free and Independent Brothers, Industrious Universal Society and the Society of St. Patrick. The last named organisation was founded specially to raise funds for the new church. Behind these organisations which comprised fifteen thousand men, marched the school children from the schools of Copperas Hill and the Hibernian School in Pleasant Street.

That year the famous Irish regiment [Connaught Rangers.] whose exploits under Wellington in the Peninsular War were still remembered, was stationed in the town. On hearing of the proposed procession they expressed a keen desire to take part in it, and the Officer in command appealed to the War Office for the necessary permission, which was readily given. Their appearance in the procession, many of them bearing signs of their services to the King, aroused the sympathies of the liberal minded non-Catholic population and kindled the enthusiasm of their countrymen to fever heat. In the absence of the Vicar Apostolic who sent his blessing, Father Penswick well and truly laid the foundation stone, and amidst the jubilation ” of the thousands of English Catholics in the town ” and the plaudits of the immense crowd of native born Irishmen, the new mission was launched on its notable career. The festivities concluded by four public banquets held in Crosshall Street, Sir Thomas Buildings, Ranelagh Street and Paradise Street.

Two years later the unfinished building began to be used and quite a surprise was felt by the average citizen at the strange and unique spectacle of hundreds of men and women kneeling outside the walls of the church on Sunday mornings, unable to obtain admission to the sacred edifice which was crowded to its utmost capacity as far as its condition permitted. Father Penswick, who was the head and front of the scheme for founding the church, made a herculean effort to finish the building. To this end he founded in his own parish an auxiliary branch of the Society of St. Patrick and raised a considerable sum of money. Many distinguished Irish ecclesiastics crossed over to Liverpool and preached in the still unfinished building; the Professor of Rhetoric at Maynooth one Sunday morning collecting two hundred pounds. Irish and English Catholics worked harmoniously until a foolish murmur was spread abroad that Father Penswick intended to put an English priest in charge of the mission and that he intended to frustrate the idea of the lay Trustees to make the ground floor of the church free for ever.

This latter proposal, afterwards carried out, is a striking light on the poverty of the masses of the people at that time. An angry correspondence sprang up in the newspapers and retarded the collection of the needed funds, but eventually the rumours were dispelled by the appointment of Father Murphy.

On the 22nd August, 1827, the church was opened by ceremonies of such splendour and solemnity as had never before been witnessed by Liverpool Catholics of any preceding age. Over forty priests were seated in the chancel, coming from all parts of Lancashire and Cheshire. As a compliment to the founder of the church, Father Penswick was invited to sing the High Mass, an eloquent sermon being preached by Father Walker (later on one of the resident clergy), who had a high reputation as a pulpit orator. The amount collected inside the church on that day reached the large sum of three hundred pounds. The papers of the day paid special attention as usual to the musical portion of the service which was of a very high character, and specifically mentioned a young priest named White whose singing attracted much public attention. He had but recently returned from his studies in Rome and was asked by Pope Leo the Twelfth to join the choir in the Sistine chapel. This flattering offer was declined; the young Levite preferring the hard work of a mission in his native Lancashire to musical fame in the Eternal City. On the Sunday following the ceremony the church was opened free to the public as had been arranged by the Trustees; a stone laid in the outer west wall inscribed with this condition stands to this hour to perpetuate this curious condition. Mr. John Brancker, one of the noblest spirited public men of a generation remarkable for the high character and unselfishness of so many of its leading citizens on the Liberal side, had given generously to the funds for the church. He gave one special gift which against his own wishes told succeeding generations of his great charity. The fine statue of St. Patrick which stands outside the church was ordered by him from a Dublin firm of sculptors and placed in position in November, 1827. It has the distinction of being the first Catholic emblem displayed to public gaze in Liverpool since St. Patrick s Cross in Marybone had been destroyed.

Thirty four years later in 1861, the future Mgr. Henry O’Bryen was the 3rd curate at the church.