“It is indisputable that while you cannot possibly be genteel and bake, you may be as genteel as never was and brew.” Charles Dickens, Great Expectations, 1861.

As we’ve already seen the decade between 1861 and 1871 seemed to have been pivotal for the family. Some have definitely succeeded, others don’t seem to do well; and by the start of the 1870’s there appears to be almost a gulf between the two remaining branches of the family, possibly exacerbated by a split in religions, but more likely by a combination of class, status, and money.

As far as we can tell, the whole family were born and christened as members of the Church of England. Roger and Charlotte were christened, and married at St Anne, Limehouse, in the late C18th, and all the children were christened there. All seem to have had C of E christenings. But at some point, there were some conversions to Rome, at least on the part of Charlotte, Frances Jane [Mother St. George], and Alfred. It’s not entirely clear why, or when.

Mother St. George is the easiest to pin down, she was professed a nun, at the age of twenty one, in 1848, the year of revolutions, and, coincidentally, the year the Communist Manifesto was published in London. So, we at least have a date as to when Mother St George was a recognized Catholic.

At the moment, this has to be speculation, but it is logical to assume that Charlotte was the first to convert, probably after the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, and almost certainly as an adult convert. Charlotte was the eldest of the brothers and sisters; sixteen years older than Mother St. George, and twenty years older than Alfred. Charlotte and Frances were the only two girls, and it’s reasonable to assume that given the amount of instruction, and the sacraments Mother St. George (Frances) would have had to received prior to her profession that she followed her sister, and they were both Catholic by, perhaps, 1844.

Alfred was the youngest of his brothers and sisters; much closer in age to Mother St. George than anyone else. He was at least eight years younger than his nearest brother John Roger, and sixteen years younger than Joe, the eldest. Quite when he converted is rather more difficult. Alfred married Laura Rose Coles in the spring of 1857 at St George the Martyr, in Southwark, in an apparently C of E marriage. He was twenty six, and she was two years younger. Laura Rose was born in Blackheath on 19th March 1833, and apparently christened into the Church of England. Alfred then married Ellen Ware in 1865 in Exeter. That marriage also seems to have been Anglican. But by 1871, his eldest daughter,Laura Mary, is being educated by the nuns in Norwood at her aunt’s convent. So it’s a reasonable bet that Alfred had become a Catholic by then.

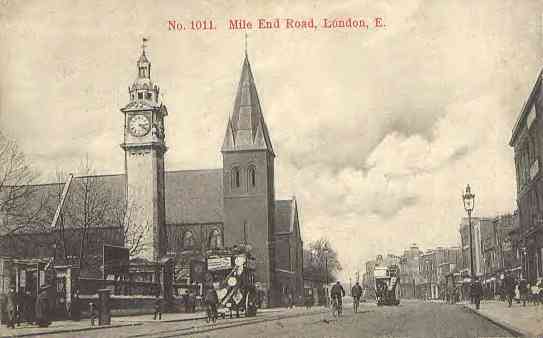

By 1871, Alfred had re-married, and had five more children. Mother St George is in the convent in Norwood. Charlotte Purssell Jnr had been dead almost two years,William is dead, and James, and his family, had been in New York for almost fourteen years, and well established on Broadway. John Roger Purssell is presumed to be in Australia, and Joe has been in Australia for at least ten years, and possibly as many as nineteen years; and finally, their mother Charlotte Purssell Senior is living in Mile End, at 350 Mile End Road, aged eighty-one, with Mary Isaacs, a sixteen year old servant girl; and her daughter-in-law, Eliza (nee Newman), William’s widow, is living at 2 Satin Road, Lambeth, also with a servant.

So the split is almost complete, possibly it is more of a drift than a split, but there are now only two of Roger and Charlotte’s families remaining in London. Alfred’s living in Finsbury Square, on the northern edge of the City, and John Roger’s in Mile End Old Town in the East End. The remaining households are Eliza Purssell, William’s widow, who is living at 2 Satin Road, in Lambeth with a nineteen year old servant Louisa Cox, and eighty-one year old Charlotte herself, who is living in Mile End Road with her servant Mary Issacs.

John Roger has emigrated to Australia sometime in the 1860’s, most probably after 1866 when his daughter Eliza was born. His wife Eliza (nee Davies) calls herself a widow, in the 1871 census, when she was living at 19 Lincoln Street, Mile End with their five youngest children. She describes herself as a house-owner, though doesn’t give herself a profession, or occupation. The usual descriptions of the well off are “living on own means” or “fundholder”, or possibly “annuitant” so while she may have had some money, but that’s by no means certain. Given JR’s rather checkered history with money, he may have left her with some, he may not. He’d gone bankrupt in 1854, and his restaurant business had failed in 1861 when he had re-invented himself as a photographer. He later re-imagines himself as a builder.

It’s not quite clear whether John Roger re-marries in Australia, but he wouldn’t be unusual in doing so. His older brother Joe had emigrated in the 1850’s and remarried, quite possibly bigamously. It seems to be quite common, so much so that Australian law seems to have permitted a second marriage if husband and wife had lived apart for seven years. Certainly, there were bigamous Australian marriages in the O’Bryen, and Elworthy families as well.

In terms of status, in 1871, Eliza is to all intents abandoned, so it’s not surprising she calls herself a “widow”, and slightly defensively as a “house owner”. At least the eldest three of her children have already died; John Junior aged two and a half in 1852, Alfred aged nine in 1860, and thirteen year old Edward in 1865. There is no trace of Albert after 1861, so it seems reasonable to assume he is dead by 1871, though he would be seventeen by then, so he could feasibly have left home. But she is living with five children, aged between five and thirteen, and no servants in the East End, quite a step down from ten years earlier when she had two. In 1871,Francis, and Charles are living with their mother, along with Arthur,Augustus, and Eliza.

All of John Roger and Eliza’s adult sons appear to have gone to Australia. Francis emigrated on the Illawarra, arriving in New South Wales on the 6th Aug 1883. Charles George seems to have emigrated some time after 1881, and died in Australia. Arthur, also, appears to have emigrated; and Augustus appears to have emigrated, married, and died in Australia as well.

John Roger Purssell returns to London by the end of the century. Crucially, JR’s youngest, and only, daughter remained in London; and it’s with her, and her family, that he lives with on his return. So at least one of the children knew their father was still alive.

By contrast, a couple of miles away on the other side of the City, Alfred is living at 49 Finsbury Square, with Ellen, who he has been married to for almost six years. They’ve had five children in the six years they’ve been married, in addition to Alfred’s daughter Laura; starting with Lucy who was born in the autumn of 1865, the year they got married, followed by Alfred Junior, Frank, Charlotte, and Agnes, none of them more than twenty one months apart, and in the case of the youngest two girls nor more than fifteen months apart. Gertrude, following the same pattern as her youngest sisters, was born fifteen months later in the summer of 1872.

Alfred is now describing himself as a “wine merchant etc employing 65 heads”, rather than a “confectioner”, which is what he called himself ten years earlier. The business is still expanding, he has increased the workforce by 30% in ten years, on top of a 25% increase in the 1850’s. But he is now clearly wanting to cement his place further as a Victorian gent. He was a subscriber to the International Exhibition of 1862 – held ten years later than the Great Exhibition- He subscribed £ 100 [ the modern day equivalent of £ 130,000]. But to quote from “Great Expectations” published ten years earlier, in a remark about Miss Havisham’s father ” Her father…. was a brewer. I don’t know why it should be a crack thing to be a brewer; but it is indisputable that while you cannot possibly be genteel and bake, you may be as genteel as never was and brew. You see it every day.” I think we can safely assume that gentility, and the wine trade are fine, but baking definitely not. So Alfred is re-inventing himself.

By this point in the century, 1871, the family has transformed itself. In two lifespans- from Roger [1783 – 1861] to the death of Alfred [1831 – 1897] his youngest son,in 1897, and over the course of the nineteenth century, at least one part of the family has done very well for itself. At least in terms of social status, I think it is fair to imagine that Alfred has come to think of himself as “genteel” in the Dickensian sense.

Roger can first be traced in the 1851 census, living in a shared house in Mile End. His neighbours can only really be described as working class, though to use a Booth definition, probably “Higher class labour”. Roger himself is, in that acutely British way of looking at class, not genteel, but he does seem to be wealthy. Roger dies in 1861, and Charlotte, then living at 1 Saville Place, in Mile End, buys a grave in Bow Cemetery [City of London, and Tower Hamlets Cemetery] where he is buried in 1861, and William Purssell is buried with his father nine years later in September 1870, aged 54.

So back to Alfred, thirty nine years old, the father of six, soon to be seven, children, and living in some splendour in Finsbury Square. In addition to his wife and children, the household contains five servants, a ratio of family to servants that he maintains for the next thirty years. I think it is safe to say this is a prosperous upper middle class Victorian household, and would regard itself as such. There is no attempt to emulate the upper classes with a butler, or footmen, just a mixture of housemaids, nurses, and a cook.

Alfred Purssell has moved a long way in ten years. In 1861 he was a twenty-nine year old widower staying with his eldest brother in Brighton with a two year old daughter. He and Laura, then lived in Blackheath, and continued to do so after Alfred’s second marriage to Ellen Ware in 1865, up to at least 1868 because Lucy, Alfred Joseph, and Frank were born there. Charlotte, Agnes, and Gertrude were all born in Finsbury Square.

In 1871 Laura Mary Purssell (aged 12) was at school at the Virgo Fidelis convent in Norwood where Mother St George was, she is shown as Frances Jane Purssell aged 42 on the census return, and listed with the rest of the nuns as “attending on the children”. Gertrude Purssell, the youngest daughter was born a year later in the summer of 1872. Her mother Ellen was 37, and within a year Ellen was dead. Alfred was forty one years old, a widower twice over, and a father of seven.

In the next snap shot in 1881, Alfred has moved house again. The family are now in Clapham, at 371 Clapham Road; though on the 3rd of April, most of the children are away at school. Lucy, Charlotte, and Agnes are boarding in Folkestone at the Convent of the Faithful Virgin. It’s a daughter house of the convent in Norwood with ” a Community of Nuns, Boarding school, and Orphanage with 17 orphans, and 13 boarders.” Mother St George is the Lady Superior, and as well as her nieces boarding there, they are being visited by Laura Purssell on the night of the census.

Both the boys are also away at school. Frank is definitely at Downside, and it’s not entirely clear where Alfred Joseph is. Given that there is only a year’s difference between the boys, it would be logical to assume he was there too, but he doesn’t appear on the census return.

At home in Clapham, are Alfred and Gertrude who is eight years old. He’s employing Annabella Norris as a housekeeper, along with a cook, two housemaids, and a children’s maid. Annabella’s position is a slightly hybrid one, similar in status to a governess. She is firmly not categorised as a servant, and was previously, and subsequently a schoolmistress. In 1851, the Norris family were living in Stroat House, in Tidenham, Gloucestershire on the edge of the Forest of Dean, where Thomas Norris described himself as a farmer of 46 acres employing two labourers. Annabella’s mother called herself a “landed proprietor” in 1861 when she and her daughters were living in a cottage in the village, and Annabella was teaching in the house with four boarding pupils. By 1871, she was running a school at 1 Powis Square, in Brighton with her sister Ellen and thirteen boarding pupils. After her stint with the Purssells, she moved to Bristol and resumed life as a schoolmistress, living at 10 Belmont Road in Montpellier, with her sister Margaret. She died in 1909 leaving the modern day equivalent of £ 264,700.

Of the remaining family, William’s widow Eliza is living in Romford; John Roger’s abandoned wife, another Eliza is nowhere to be found but seems to have died in Dartford five years later. James and his family have been established in New York for nearly twenty years, and his five youngest children were all born in New York City, and Charlotte Purssell still seems to be alive, dying five years later in the winter of 1886 in Romford at the age of ninety-six.