Dorothy Bell was the daughter of Arthur Smith-Barry, Lord Barrymore. So she is a second cousin of Pauline Barry (nee Roche)’s granddaughters Nina, and Emily, who are in turn, Mgr Henry, Corinne, Basil, Alfred, Philip, Rex, and Ernest O’Bryen‘s third cousins. Dorothy’s father had owned Fota House, which was inherited by his brother James, and then his nephew Robert. Dorothy Bell bought the estate back from her cousin Robert in 1939, for £ 31,000. Quite how the family managed to hold onto their land, and money given Lord Barrymore’s behaviour to his tenants in the 1880’s is some mystery, as is the following description of life at Fota House in the 1940’s. Essentially, it wouldn’t have been much different at any time in past hundred and fifty years.

The following description of life at Fota House is largely taken from ‘Through the Green Baize Doors: Fota House, Memories of Patricia Butler’ , and various interpretations of it in the Irish Times, and Irish Independent about five years ago. The subtle distinctions between Irish and English staff, – Two weeks holiday for Irish staff, and a month for English staff, separate dining rooms, and an acceptance of the big house having hot and cold running water while there was none in the village, and the “Oh weren’t the gentry lovely” take on things appears to be a perfect example of false consciousness. Over to Patty Butler.

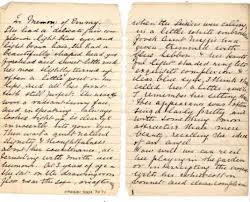

Back in the 1940s, when Dorothy Bell — mistress of the Big House at Fota — arrived home from a day’s hunting, she never did so quietly. She would, recalls former maid Patty Butler, rush through the front door, ringing the bell, and stride through the hall and up the stairs, calling the servants one after the other, “Mary!” “Patty!” “Peggy!”, discarding as she went her picnic basket, jacket, the skirt she wore over her jodhpurs for side-saddle riding, her whip and her hunting hat. As the staff, including the butler, rushed to pick up Dorothy’s belongings, her lady’s maid hurried to run a bath.

Patty was just 23 when she started work as the “in-between maid” at Fota House in 1947, after returning to Cork from England. On the advice of her cousin Peggy, who was working in Fota as the parlour maid, Patty applied for the job.

On the day of the interview, a somewhat awed Patty, who came from the nearby village of separate, was shown into the library by the butler, George Russell. “To me, the inside of Fota House on that day seemed like a palace,” she recalls. “I felt very small but also very excited in the midst of all this grandeur.” She was greeted by the mistress, who was sitting at a desk. The interview was brief. “Patty, have you come to join us?” inquired Dorothy. “The housekeeper will show you your duties. It won’t be all clean work, so you won’t be dressed up as you are now. Mrs Kevin will tell you what to wear.” And with that began a quarter of a century of dedicated service, as Patty became a member of staff in the efficiently run, though sometimes-eccentric, household a few miles outside Cobh. Over the years she was promoted to housemaid, lady’s maid and eventually cook.

Before Patty’s arrival, the family — The Honourable Mrs Dorothy Bell, her husband Major William Bertram Bell and their three daughters, Susan, Evelyn and Rosemary — had been looked after by an army of servants. According to the census return for 1911, 73 people were on site at Fota House on Sunday, April 2nd, 1911. None of them were the Smith-Barry family who had lived in Fota House for generations, as records show they were away on holiday at the time. In the 1930s, an estimated 50 men had worked on the grounds of Fota alone, but by the time Butler took up employment in the Big House in 1947, overall staffing levels had fallen to about 13.

“I began working in Fota House in 1947. I worked there for about 25 years. I was initially employed as an in-between maid but later I worked in almost every capacity, as a housemaid, cook and housekeeper. The cook, Mrs Jones, who came to Fota with Mrs Bell from England, left after 45 years so Peggy Butler, my cousin, and I managed the cooking for Dorothy, her husband, Major Bell, other members of the family and visitors.”

“Mrs Bell had a secretary too, Miss Honor Betson. She had an estate agent and clerical staff who lived in the courtyard. Mr Russell, the butler from Yorkshire in England, supervised the household until he died on January25th, 1966. He died in Fota House.”

“There was a lovely homely feeling there. It was a very pretty house and Mrs Bell was very into flowers, so it was always lovely and very pretty,” recalls Patty, now 87.

“There was a lovely homely feeling there. It was a very pretty house and Mrs Bell was very into flowers, so it was always lovely and very pretty,” recalls Patty, now 87.

She was given her own comfortable bedroom in the servants quarters. “I had everything I needed: a bed, a wardrobe, a dressing table with a mirror and an armchair near the fireplace. I remember also a beautiful washstand shaped like a heart with three legs. On top of that, there was a jug and basin with a matching soap dish. “There was also a towel rail with a white bath and hand towel. All the servants’ rooms were similar.”

“There was some distinction between the upper (mostly English and Protestant) servants, and the lower (mostly Irish and Catholic) servants. We dined in separate rooms, the upper servants in the housekeeper’s room and the lower servants in the still room. But we were all the best of friends. There was no rivalry or no animosity.”

“We also enjoyed food and board. The food was fabulous in Fota, of course, as fresh fruit and vegetables were produced there all the year round in the market garden and in the fruit garden and orchard. From the farm in Fota came milk, cheese, butter and cream. Rabbit and pigeon were eaten regularly in those days. The servants ate the same as the Anglo-Irish family, more or less.”

The anecdotes are legion — the way the servants occasionally ‘borrowed’ the Major’s Mercedes to go to Sunday Mass when their van didn’t work. How the housekeeper, a kindly soul with a strong Scottish accent, kept a cupboard in her bedroom especially for the pieces of china she broke while dusting Dorothy’s treasured ornaments. The times the servants were all driven to Cork Opera House by the chauffeur — the Bells had a great affection for the theatre and felt their staff should enjoy it too.

And then there was Dorothy’s eccentric habit of cutting the fruit cake in such a way that nobody could take a slice without her knowledge, and, of course, the parties that took place when the Bells were away, travelling the world.

Local lads from the village were invited up to the Big House by their sisters for a bath and a fry-up — there was no running water in many houses until the 1950s, or even the 1960s, says Patty. However, Fota had its own generator for electricity and water was always supplied from a nearby well. “We’d fry them up rashers and sausages and they’d have the bath and use the beautiful big, soft white towels and they’d think they were in heaven. The boys would love the bath — they were in their 20s and wanted to go into Cobh all poshed up!”

One day, however, Dorothy remarked that she had received an anonymous letter claiming that Patty and Peggy were having “parties” in the house while she was away. As Patty stood there, quaking, Dorothy laughed and told her relieved maid that she had thrown the letter in the fire.

Every morning, Mrs Kevin’s bell rang at 7am. Patty rose, dressed in a blue dress with a big white apron and white cap, and set to her housekeeping duties, which included cleaning the Major’s study and hoovering, dusting and polishing the Housekeeper’s Room before having breakfast at 8am. At 8.45am, Patty would bring her assigned guest — Fota nearly always had guests — morning tea on a tray with dainty green teapots with a gold rim and matching teacups. “I’d wake her in the morning with a breakfast tray and a biscuit, open the shutters, pull back the curtains and tidy the room. If there were any shoes that needed to be polished, I would take them down and they would be polished by a man who came in.”

The bed linen was beautiful. Each linen pillowcase had the Smith Barry crest in the corner and frills around the edges. After ironing, Patty remembers, each frill had to be carefully “goofed” or “goffered” by hand until it was perfectly fluted.

The gentry came down for breakfast — kippers, kedgeree, rashers, sausages and eggs or boiled eggs, served with toast and fresh fruit from the garden — each day at about 9am. “You always knew they were gone down because their bedroom doors would be open. So you’d go up and make the beds and tidy the room and wash out the bathroom — but you had to be back behind the green baize door by 11am.” In the evenings, she wore a black dress with a small apron and a smaller white cap with a black velvet ribbon. Male servants also wore black.

The gentry came down for breakfast — kippers, kedgeree, rashers, sausages and eggs or boiled eggs, served with toast and fresh fruit from the garden — each day at about 9am. “You always knew they were gone down because their bedroom doors would be open. So you’d go up and make the beds and tidy the room and wash out the bathroom — but you had to be back behind the green baize door by 11am.” In the evenings, she wore a black dress with a small apron and a smaller white cap with a black velvet ribbon. Male servants also wore black.

“There was always lots to do,” she recalls. After the morning household tasks came lunch. “I’d be helping in the pantry and at the lunch. There was a long walk from the kitchen to the dining room — it was three or four minutes, but there were no trollies, so everything was carried by hand.” Lunch — which could be anything from roast beef to pigeon pie, rabbit, fish soufflé or cold meat in aspic jelly with vegetables from the garden, water and a selection of wines — could last from 1pm to 2.30pm.

Tea was at 5pm in the Gallery in summer and in the library in winter. “Tea, for which there were cucumber and marmite sand-wiches, scones, tea and a cake, could last until 6.30pm,” she says.

Tea was at 5pm in the Gallery in summer and in the library in winter. “Tea, for which there were cucumber and marmite sand-wiches, scones, tea and a cake, could last until 6.30pm,” she says.

At 7pm, the gentry would go up to their bedrooms to change and have a bath before dinner — a lengthy four or five-course affair, which usually included game from Fota Estate. “Each dinner was served with suitable trimmings. Butter and cream were used in food preparations, so the flavours were always delicious,” she says. The kitchen had meat from the cattle and Fota’s home-produced milk, cheese and butter, as well as veg and fruit from the garden.

“There were always visitors, there was always somebody staying. They had the shooting season, the fishing season, the tennis season, the seaside in summer, the hunting — all the seasons brought different activities. You’d know by the season what was happening.”

Christmas was a particularly memorable time, she recalls. A single large Christmas tree was placed in the Front Hall, decorated with streamers, silver balls and other decorations, and on Christmas morning Dorothy gave each of the staff presents. “I remember I got a white apron,” recalls Patty, who says the mistress also distributed gifts to her tenants.

“On Christmas morning, the family went to the library to exchange presents. They loved gifts such as books and music records, ornaments or exquisite boxes of chocolates.” The chocolates, she says, often lasted for weeks, as the family usually ate only one at a time.

On Christmas Day, the servants had Christmas dinner in the middle of the day in the Servants’ Hall, while the family helped themselves to a cold lunch in the dining room. “This was the only day of the year that they waited upon themselves so that we could enjoy our Christmas dinner,” Patty recalls. That evening, the servants lined up in the Hall to watch the family, in full fancy-dress — these clothes were stored in a special chest in the attic — parade into the dining room.

“We had to bow to them as they passed by. I remember one year in particular when I could scarcely stop myself from laughing. Mrs Kevin, the housekeeper, carried a bell behind her back and as she bowed to each individual, the bell rang out!” After the fancy-dress parade, the family enjoyed a traditional Christmas dinner followed by plum pudding. They later drank to each other’s health from a silver ‘loving cup’, which was passed around. The men played billiards and the women talked and drank coffee in the library until late in the evening.

There were plenty of famous guests at Fota: Lord Dunraven of Adare, Co Limerick, Lord Powerscourt from Wicklow, the Duke and Duchess of Westminster and, according to the Visitors Book of Names, “eight international dendrologists with illegible signatures”.

The Bells enjoyed life, Patty recalls. “They had a lovely life; they were into everything. They went to the Dublin Horse Show and to the summer show in Cork. In his study, the Major had pictures of the bulls and cows with their first-prize rosettes. “They had a very privileged life and they enjoyed it,” she continues. There always seemed to be plenty of money. Mrs Bell had her own money, while the Major was, says Patty, “supposed to be a wizard on the stock exchange. They also had the farm and they owned a lot of houses and property in Cobh and Tipperary”.

In the evenings, Patty recalls, it was her job to go back upstairs, remove bedspreads, turn down beds and prepare hot-water bottles. “Some guests brought their own beautifully covered bottles, otherwise, stone jars were used. Most ladies brought their own pillows covered with satin pillowcases because they believed satin did not crease the face. “They had pink satin nightdress cases covered with lace and tied with ribbons.”

Fota House, Patty remembers, was a home from home. “It was a very happy place. Mrs Bell was excitable and eccentric. She was very athletic and quick. It was a very happy time, all of it. In every household little things will happen to ruffle your feathers but, overall, it was a fabulous place to work, and it was the people who made it.”

“There were lovely people at Fota,” she continues. “They were extraordinary. There were men who were extraordinary craftsmen — there was a blacksmith, for instance and a shepherd and a stone mason. They’d usually have a young apprentice that they would be training up.”

By the 1960s, however, most of the servants had left. “There was only me and Peggy running the house. Pat Shea was the last butler. Little by little, the staff dwindled away: the cook left, the ladies’ maid left.” When George Russell died in 1966 — he had been butler at Fota for 45 years and came with the Bells from England — it was the end of an era, she recalls. “Mr Russell told me he would love to write a book about Fota. He was going to call it, ‘What the Butler Saw’.”

The household slowly began to change. A series of nurses were employed to nurse Major Bell in his declining years until he died. Dorothy moved to the Gardener’s House, which was situated in the orchard at Fota, and lived there until she died a few years after her husband, in 1975.

The estate today comprises 47 hectares of land, including the parkland, gardens and arboretum. In December 2007, the Irish Heritage Trust took over responsibility for Fota House, Arboretum & Gardens.

‘Through the Green Baize Doors: Fota House, Memories of Patricia Butler’ — a revised edition of ‘Treasured Times’ transcribed and arranged by Eileen Cronin