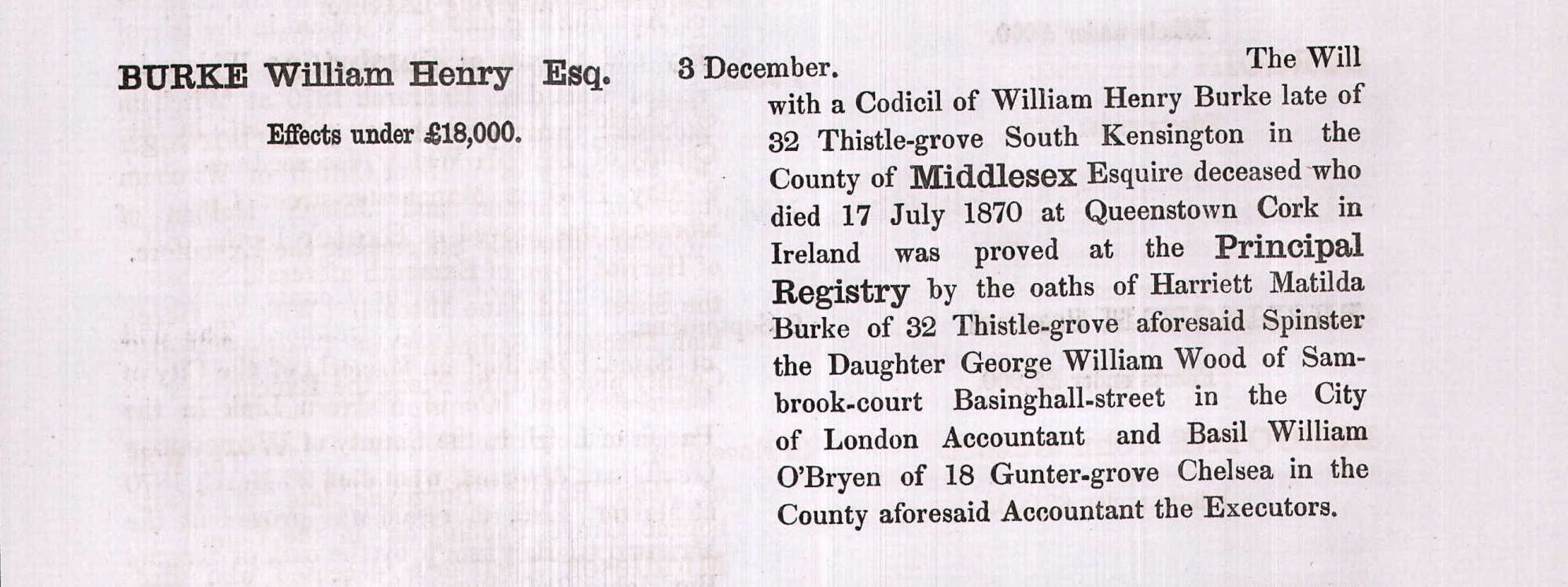

For reasons I’m not entirely sure why, there has been a large increase in interest in the post I did just over two years ago about the will of William Henry Burke (1792-1870). This got me to look at him again, and to see what else could be put together. This is the second of a series of posts that should explain a lot more. If you haven’t read the first one you can find it here. My starting point for looking at William Burke was one of his sons-in-law Basil O’Bryen. But everything is much more complicated than that.

To re-cap slightly.

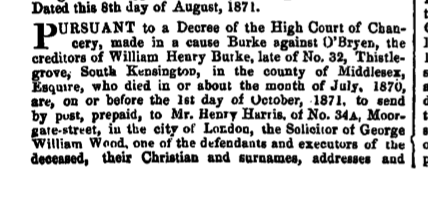

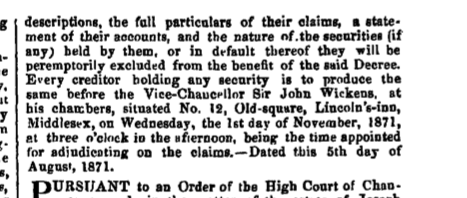

William Henry Burke and John Roche O’Bryen [Basil’s father] were neighbours in South Kensington. Both men drew up new wills in May 1870, and died in July that year. What raised my curiosity was the fact that neither of WH Burke’s elder children, or their spouses were made executors, and he chose his youngest daughter, and her twenty-two year old fiancé Basil. Basil O’Bryen had stood out very early on. Mostly, because he is a wrong’un; he married three times, at least once bigamously [at least according the English law] in Australia. He abandoned his son from his marriage to Harriet, and his second wife and their two children, and moved to Australia, where he married his third wife. There is also signs of at least one court case, with reference to a court case Burke v. O’Bryen in a London Gazette notice in August 1871.

So on with the story.

There’s something about the Basil and Harriet story that I just can’t get at the moment. In brief, it reads like the plot of a novel. They marry when he is twenty-two, and she is thirty-three. I still can’t work out whether it’s love, money, or both. His father left £1,000 [present-day value £750,000] to the trust Harriet was a beneficiary of when he drew up his new will. The other parties to the settlement being his daughter Corinne, and Basil’s step-mother Celia. Presumably, there were already funds in the trust, initially I thought it seemed to be a Marriage Settlement, but I am beginning to think that it was a settlement to provide income for both Corinne, and Harriet. John Roche O’Bryen’s will is very detailed, quite long, and very specific with regard to provision to the children of his second marriage to Celia Grehan. There is a great lack of detail about any of his adult children, apart from the reference to the settlement. The reason, I now think, it may be a settlement for adult female members of the family is the will very clearly states that any sums provided for daughters should be “settled upon daughters in manner following, that is to say. Upon trust, to pay the income thereof respectively to such daughter for her sole and separate use, free from the control of her husbands.” But this doesn’t really help with where Basil got any money from, and when. The best guess is that there was money from Eliza Henderson [ JROB’s first wife], his mother, and that both Henry Hewitt, and Basil had benefitted from that already.

The marriage lasted just thirty-one months, and Harriet was dead by the end of August 1873, leaving Basil a twenty-five year old widower, with an eleven-month old son Basil John. All very tragic, but Basil bounces back, and is re-married within nine months of Harriet’s death. He is now twenty-six, and his bride Agnes Kenny is twenty-three.

Basil and Harriet’s marriage also raises questions about who the families are. The main one is why were they married by the Archbishop of Westminster? Marrying in the pro-Cathedral makes sense because it is fairly close to Thistle Grove, and was probably the parish church at the time. Archbishop [later Cardinal] Manning seems to be a rather grand celebrant for the wedding, particularly as Harriet had been christened as an Anglican, at St Leonard’s Shoreditch, as had her brother, and sister. But perhaps, as Manning was a convert himself, he looked fondly on bringing Anglicans to the true Church. Elizabeth Burke, Harriet’s sister also married a Catholic.

What is interesting is how connected to the Burke family he seems to remain, at least initially. Or possibly more correctly, how connected to Burke property he is. According to the London Gazette William Henry Burke of No 32 Thistle grove South Kensington, had his will proved by amongst others, Harriet Matilda Burke of No 32 Thistle grove and Basil William O’Bryen of No 28 Thistle grove. So in December 1870, they each gave their father’s addresses as theirs. On the census date, April 2nd 1871, they both were listed at his step-mother’s address No 28 Thistle grove, where they were described as “visitors”. But the probate record for Harriet – slightly strangely not proved until 30th August 1875, two years after her death, gave her principal address at the time of her death as No 32 Thistle grove, which was also the address that Basil gave when he proved the will. So five years after William Henry Burke’s death, and two years after Harriet’s, her widower is apparently still connected to the Burke family home. Even though during that time, Harriet had given birth to their son Basil junior in Torquay, and she died at 34 Cavendish Place, Eastbourne. Her probate record recorded her as “late of 32 Thistle grove”. She left just £100.

The next nugget came from a small story in “The Tablet” [The International Catholic News Weekly.]

THE PRO-CATHEDRAL—A pleasing addition has lately been made to the Pro-Cathedral of Clifton. The side chapel, dedicated to St. Joseph, has been entirely renewed and decorated, and a marble altar erected, the reredos of which was executed in Belgium. The whole has a very pleasing effect. It is the gift of Basil O’Bryen, esq., as a memorial of his late wife Harriet Matilda O’Bryen, who died August 23, 1873, and whose remains are buried in the cemetery at Fulham. [Page 18, The Tablet, 5th February 1876.]

This is also very curious. There doesn’t appear to be any family connection between the Burke family, and Bristol. In fact, far from it. William Henry Burke gave his birthplace as the “City of London”, and Sarah Burke (neé Penny) and all the children were recorded as being born in London in the 1841 census when they were living in Noble Street in the City. [Noble Street is north-east of St Paul’s]. There is an O’Bryen Bristol connection, John Roche O’Bryen had practiced medicine there from at least 1841, and Basil himself was born there, and his mother, and six brothers and sisters, are buried in the city. But by the time Basil was 10 the O’Bryen family were in Liverpool, and by 1861, when he was 12, the family were in London, and he was at boarding school at Ratcliffe College.

It’s an interesting public gesture, and all the odder for the eccentric choice. A memorial in the Pro-cathedral in London would have seemed more obvious, given that Basil and Harriet got married there, or a memorial at St Thomas of Canterbury in Fulham, where John Roche O’Bryen, Basil’s step-brother Walter, and Harriet were buried; followed twenty-five years later by his step-mother Celia, and, later still, by another step-brother Philip. Perhaps Basil felt the need to try to repair his father’s somewhat sullied name in Bristol.

But there is still the question about why Basil and Harriet were her father’s executors, and more particularly, in a rather patriarchal age, WHB didn’t choose either his son, or a long-established son-in-law.

The Burke children were

- Elizabeth Sarah (1829 – 1889)

- William Henry ( 1835 -1908)

- Harriet Matilda (1838 – 1873)

In 1870, the eldest daughter Elizabeth Sarah was forty years old , and had been married for fourteen years, all five of her children had been born, her eldest son was about eleven years old. In one of those nice twists, and coincidences, Elizabeth and Alfred Edwardes’ second son, nine year-old, Henry Grant Edwardes would go on to marry Lucy Purssell, whose sister Gertrude married Basil’s step-brother Ernest O’Bryen in 1898. So Basil’s nephew was his step-brother’s brother-in-law.

His only son William Henry, known as Henry, was thirty-five, had been married nearly nine years, and was the father of four children, with another one on the way. Yet the choice of executors was the youngest unmarried daughter, and her much younger fiancé.

So is the answer to be found in Burke v. O’Bryen ?