This is the start of a slight Hornblower moment or two. Robert Hall is Mary Roche’s (neé Verling) son by her first marriage to “Captain Hall”. She is 4 x Great-Granny He is John Roche’s step-son.

The starting point for this post was coming across a couple of cuttings from the Irish Times, and the Irish Independent.

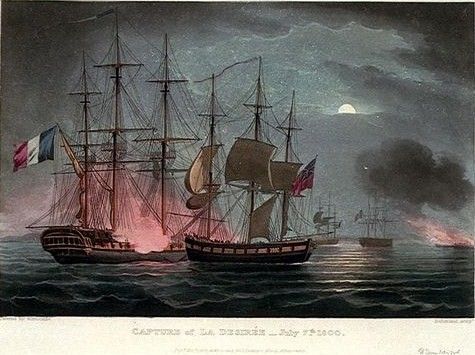

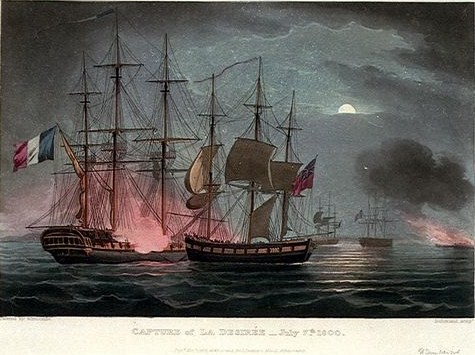

Irish Times, Saturday 22 January 2005. A rare Irish silver freedom box, right, giving the Freedom of the City of Cork dating from 1808 is up for auction at John Weldon next Tuesday (25th January 2005) with an estimate of €10,000-€15,000. The square box is hallmarked Dublin 1808 and is inscribed with the City of Cork arms and an inscription. It was presented to a Captain Robert Hall on August 22nd, 1809 for gallantry for his part as a midshipman on board The Dart in battle with four Dutch gunboats in 1796 and with a French frigate in July 1800.

The inscription reads: ” With this box the Freedom of the City of Cork in Ireland was unanimously given to Capt Robert Hall for his gallant conduct in his Majesty’s Navy the 22nd day of August 1809 “.

Irish Independent; 3 Apr 2015 – A Cork Freedom Box, made in Dublin in 1808 and given to the naval officer Captain Rob Hall for gallant conduct in the Napoleonic wars, sold at John Weldon Auctioneers on March 24 for €5,500.

So some local recognition of a local naval hero. But we need a little more. From the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (edited) we can get the following: HALL, Sir ROBERT, naval officer; baptized 2 Jan. 1778 in County Tipperary (Republic of Ireland); his father remains unidentified, while his mother is known only through the probate of his will, where she appears as “Mary Roche, heretofore Hall”; Robert Hall’s early years have not attracted the attention of naval biographers. It is known, however, that he was gazetted a lieutenant in the Royal Navy on 14 June 1800, a commander on 27 June 1808, and a captain on 4 March 1811.

The Canadians go on at some length about Rob Hall’s career and achievements in Canada, but seem to have missed his early “gallant conduct”. The information with the presentation of the freedom box is for his “gallantry for his part as a midshipman on board The Dart in battle with four Dutch gunboats in 1796 and with a French frigate in July 1800”. So what was this early gallant conduct. It turns out to be the capture of Dutch ships in the Zuiderzee in 1799, not 1796, and a French frigate in 1800.

Rob Hall, later Sir Robert Hall [ 1778 -1818 ] is Mary Roche (neé Verling) son by her first marriage to “Captain Hall”. He is John Roche’s step-son, and John Roche O’Bryen’s step-uncle. He seems to have had a distinguished naval career, and the Dictionary of Canadian Biography closes its entry on him as follows ” An affable, gallant, and cultivated officer, Hall in his Canadian posting had proved himself a conspicuously fair-minded, innovative, and efficient administrator. His heirs were a natural son, Robert Hall, born in 1817 to a Miss Mary Ann Edwards, and his mother Mary Roche, who was his residuary legatee. The son, baptized on 2 Nov. 1818 by George Okill Stuart, rector of St George’s Church in Kingston, became a vice-admiral in the Royal Navy and died in London on 11 June 1882 after having served for ten years as naval secretary to the Admiralty. “

I really like the fact that he acknowledged and provided for a bastard son, and was happy for it to be acknowledged in the family, and according to the Pedigree of the Verlings of Cove by Dr. Gabriel O’Connell Redmond, ” An obelisk was erected to his memory in Aghada Wood by his stepfather John Roche of that place.”; so they certainly weren’t ashamed of him. There is more work to be done on the early life, but there is certainly evidence that his step-sister Mary Roche seems to have been born in Ireland in 1780, and died in 1852, according to the obituary notice “Mary O’Brien, relict of the late Henry Hewitt O’Brien, aged 72,”. Her probate notice spells the name O’Bryen, but notes the will spells it O’Brien. So it seems highly likely that Mary Hall (neé Verling) had re-married as a widow with a son under the age of two, and that John and Mary Roche brought up three children. Mary’s son Rob Hall, and then Mary Roche junior, and, finally, John Roche junior, who was one of the parties to his sister’s [Mary Roche junior] marriage settlement in 1807.

So back to the Canadians.

It is known, however, that Robert Hall was gazetted a lieutenant in the Royal Navy on 14 June 1800, a commander on 27 June 1808, and a captain on 4 March 1811. He attracted attention for sterling service in the defence of a fort on the Gulf of Rosas, Spain, in November 1808 while in command of the bomb-ketch Lucifer. On 28 Sept. 1810 he enhanced his reputation when, as commander of the 14-gun Rambler, he captured a large French privateer lying in the Barbate River, Spain.

This does provide one slight problem if the inscription on the freedom box is correct. The inscription reads: ” With this box the Freedom of the City of Cork in Ireland was unanimously given to Capt Robert Hall for his gallant conduct in his Majesty’s Navy the 22nd day of August 1809 “. If the inscription is right, then the Canadians are wrong because they don’t make Rob a captain until 1811. If the Canadians are right, then the City of Cork has promoted him early.

More from the DCB. In September 1811 Hall was appointed to command a flotilla entrusted with the defence of Sicily against naval forces operating from French-occupied Naples. He achieved a major success at Pietrenere (Italy) on 15 Feb. 1813 in a raid on a convoy of about 50 armed vessels, French supply ships escorted by many Neapolitan gunboats. With only two divisions of gunboats carrying four companies of the 75th Foot he neutralized the enemy’s shore batteries and captured or destroyed all 50 ships. In recognition of this feat he was made a knight commander in the Sicilian order of St Ferdinand and of Merit. Permission to accept this honour was granted by the Prince Regent on 11 March, at which time Hall was described as a post-captain and a brigadier-general in the service of Ferdinand IV of Naples.

The DCB goes into rather greater detail once Rob Hall arrived in Canada. It is probably considerably more interesting to Canadians so there is a link to the full entry here. My version is edited from the full version. On 27 May 1814. Hall was designated acting commissioner on the lakes of Canada, to reside at Quebec; his actual headquarters would be the naval dockyard at Kingston, Ontario. [Kingston is at the junction of Lake Ontario, and the St. Lawrence River, and was the main naval headquarters for the British Great Lakes fleet]. He was not immediately available and did not report for duty in Kingston until mid October. His new assignment involved a dual responsibility: to the commander-in-chief on the lakes, Sir James Lucas Yeo, for the building, outfitting, supply, and maintenance of naval vessels, and to the Navy Board in London for the administration of the navy yard at Kingston and its dependencies on the Upper Lakes and Lake Champlain, and all naval victualling and stores depots in the two provinces.

The British and the Americans were in the middle of the War of 1812 [which actually lasted from 1812 – 1815]. Robert Hall’s arrival in Canada was at an interesting time; almost eight weeks earlier, a British attack against Washington, D.C., resulted in the “Burning of Washington”. On August 24, 1814, after defeating the Americans at the Battle of Bladensburg, a British force led by Major General Robert Ross occupied Washington and set fire to many public buildings, including the White House, and the Capitol. It marks the only time in U.S. history that Washington, D.C. has been occupied by a foreign force. The new commissioner’s immediate concern was the implementation of Yeo’s plans for a decisive campaign against the Americans in 1815. These involved the completion or construction of five frigates, two ships of the line, a number of gunboats, and brigs, To this ambitious program Hall made an important addition: a scheme to rid the naval units of transport duties He sent this proposal to the Navy Board, but all plans for a campaign in 1815 became redundant when the Governor was notified of the ratification of an Anglo-American peace signed at Ghent (Belgium) on Christmas Eve 1814.

The peace posed immediate and serious problems for Hall and his staff. The yard and its dependencies had incurred expenses of some £40,000 in wages alone in 1814, the building of the St Lawrence had been immensely costly, and a huge outlay was required to pay for the ships under construction. Prudence dictated the maintenance of a strong fleet for the time being. In March 2015, Hall was dispatched to England for consultations with the Admiralty about the future naval establishment in the Canadas.

Hall remained in England for more than a year, during which time the British government was engaged in negotiations with the United States which eventually led to the Rush–Bagot agreement of April 1817 to demilitarize the lakes. On 29 Sept. 1815 Hall was named commander on the lakes and resident commissioner at Quebec, thus combining the two senior naval appointments in the Canadas. The first authorized him to style himself commodore; the second confirmed him in the post of commissioner. He was knighted on 15 July 1816 and, distinguished with the additional honour of a companionship in the Order of the Bath, returned to Kingston on 9 September 1816.

He was seriously ill with a lung infection in October 1817, recovered sufficiently to return to duty for a few weeks at the end of the year, but died of this disease at his quarters at Point Frederick on 7 Feb. 1818. An affable, gallant, and cultivated officer, Hall in his Canadian posting had proved himself a conspicuously fair-minded, innovative, and efficient administrator. His heirs were a natural son, Robert Hall, born in 1817 to a Miss Mary Ann Edwards, and his mother Mary Roche, who was his residuary legatee. The son, became a vice-admiral in the Royal Navy and died in London on 11 June 1882 after having served for ten years as naval secretary to the Admiralty.