There seem to be some professions that run through the family again, and again. One that I hadn’t really paid much attention to until recently was the navy. It is an almost completely Irish thing, and is largely members of the family who were born, brought up, and lived in co. Cork. Starting furthest back [great grandpa x 5] Henry Hewitt was a Customs Officer, specifically at one time Captain of the Beresford Revenue Cutter. Then the Verling family pick up the strain. Bartholomew Verling of Cove, co. Cork and Anne O’Cullinane,[also great grandparents x 5] had five children, both daughters married naval captains, and of the three sons, Edward was a “Staff Captain R.N”, another Garrett “died at sea”, and the eldest son John Verling didn’t appear to go to sea, but his second son was James Roche Verling (1787 – 1858) who was a naval surgeon, and attended Napoleon Bonaparte on St. Helena. John Verling and Ellen Roche also had a daughter Catherine who married Henry Ellis “Surgeon R.N.”.

There seem to be some professions that run through the family again, and again. One that I hadn’t really paid much attention to until recently was the navy. It is an almost completely Irish thing, and is largely members of the family who were born, brought up, and lived in co. Cork. Starting furthest back [great grandpa x 5] Henry Hewitt was a Customs Officer, specifically at one time Captain of the Beresford Revenue Cutter. Then the Verling family pick up the strain. Bartholomew Verling of Cove, co. Cork and Anne O’Cullinane,[also great grandparents x 5] had five children, both daughters married naval captains, and of the three sons, Edward was a “Staff Captain R.N”, another Garrett “died at sea”, and the eldest son John Verling didn’t appear to go to sea, but his second son was James Roche Verling (1787 – 1858) who was a naval surgeon, and attended Napoleon Bonaparte on St. Helena. John Verling and Ellen Roche also had a daughter Catherine who married Henry Ellis “Surgeon R.N.”.

Edward Verling, the “Staff Captain R.N”, had three children The eldest son Bartholomew Verling (1797 – 1893) was another naval surgeon, and Mary Verling married Capt. Leary R.N. Edward Verling’s sister, another Mary Verling married first a Captain Hall, and the secondly John Roche of Aghada [great grandparents x 4]. Mary Roche (neé Verling) had the distinction of being the mother of a Commodore, and grandmother of a vice-Admiral, albeit a bastard grandson. Finally, their nephew, another Bartholomew Verling (1786 – 1855) was Harbourmaster of Cobh, and also the Spanish Consul there.

So a lot of boating. What this did pose was the question why the navy? The logical answer was why not? It is estimated that around a quarter of the Royal Navy crew present at Trafalgar were Irishmen. It was regarded as a profession certainly at officer level, and was well paid. In 1793 a captain’s pay rate ranged between £100 – £336,[£128,000 – £433,000 at today’s value] and by 1815 this had risen to £284 – £802.[£212,000 – £600,000 at today’s value]. After 1806, a naval surgeon’s salary was set at 10s. per day for less than 6 years experience, up to 20s. per day for over 20 years experience £182 – £ 365 [£164,000 – £328,000 at today’s value]. So, apart from the minor problem of being killed, it was very well paid. But in addition to the pay ( especially if you were an officer) was the prize money paid for capturing enemy ships.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, captured ships were legally Crown property. In order to reward and encourage sailors’ efforts at no significant cost to the Crown, it became customary to pass on all or part of the value of a captured ship and its cargo to the capturing captain for distribution to his crew. Similarly, all warring parties of the period issued Letters of Marque and Reprisal to civilian privateers,[essentially legal pirates] authorising them to make war on enemy shipping; as payment, the privateer sold off the captured booty.

This practice was formalised via the Cruisers and Convoys Act of 1708. An Admiralty Prize Court was established to evaluate claims and determine prize money, and the scheme of division of the money was specified. This system, with minor changes, lasted until the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

If the prize were an enemy merchantman, the prize money came from the sale of both ship and cargo. If it was a warship, and repairable, usually the Crown bought it at a fair price; additionally, the Crown added “head money” of £ 5 per enemy sailor aboard the captured warship. Prizes were keenly sought, for the value of a captured ship was often such that a crew could make a year’s pay for a few hours’ fighting. Hence boarding and hand-to-hand fighting remained common long after naval cannons developed the ability to sink the enemy from afar.

All ships in sight of a capture shared in the prize money, as their presence was thought to encourage the enemy to surrender without fighting until sunk.

The distribution of prize money to the crews of the ships involved persisted until 1918. Then the Naval Prize Act changed the system to one where the prize money was paid into a common fund from which a payment was made to all naval personnel whether or not they were involved in the action. In 1945 this was further modified to allow for the distribution to be made to Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel who had been involved in the capture of enemy ships; however, prize claims had been awarded to pilots and observers of the Royal Naval Air Service since c.1917, and later the RAF.

The following scheme for distribution of prize money was used for much of the Napoleonic wars, the heyday of prize warfare. Allocation was by eighths.

- Two eighths of the prize money went to the captain or commander, generally making him very wealthy.

- One eighth of the money went to the admiral or commander-in-chief who signed the ship’s written orders (unless the orders came directly from the Admiralty in London, in which case this eighth also went to the captain).

- One eighth was divided among the lieutenants, sailing master, and captain of marines, if any.

- One eighth was divided among the wardroom warrant officers (surgeon, purser, and chaplain), standing warrant officers (carpenter, boatswain, and gunner), lieutenant of marines, and the master’s mates.

- One eighth was divided among the junior warrant and petty officers, their mates, sergeants of marines, captain’s clerk, surgeon’s mates, and midshipmen.

The final two eighths were divided among the crew, with able and specialist seamen receiving larger shares than ordinary seamen, landsmen, and boys. The pool for the seamen was divided into shares, with:

- each able seaman getting two shares in the pool (referred to as a fifth-class share),

- an ordinary seaman received a share and a half (referred to as a sixth-class share),

- landsmen received a share each (a seventh-class share),

- boys received a half share each (referred to as an eighth-class share).

An example of how large the prize money awarded could be was for the capture of the Spanish frigate Hermione on 31 May 1762 by the British frigate Active and sloop Favourite. The two captains, Herbert Sawyer and Philemon Pownoll, received about £65,000 apiece,[£115m.at today’s value] while each seaman and Marine got £482–485. [£854,700 – £860,000 at today’s value]

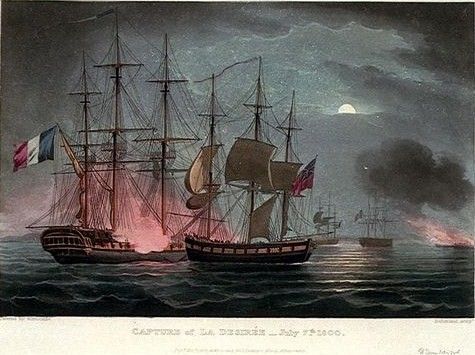

Robert Hall would definitely have benefited from prize money. He was involved with the capture of the French frigate Desirée in Dunkirk in 1799, and later he captured a large French privateer lying in the Barbate River, Spain in 1810.