CHAPTER XII.

When Mr. Walmsley returned from his mission to London [in early 1839], as representative of Liverpool in the little Parliament assembled at Brown’s Hotel, the experience it had given him of political life, its richer tone, its larger scope, its all-embracing interest, wrought its full effect upon him. Wider horizons opened before him than those which bound the sphere of local politics ; and before he was elected mayor of Liverpool he had already resolved he would one day enter Parliament. He was not without compeers who cavilled at the ambition of this self-made man.

Mr. Walmsley often related with gusto the effect produced upon one of the local magnates on hearing of his new resolve to enter Parliament :

“ Returning from my mission to London, as member of the Anti-Corn-Law Delegation,” said Mr. Walmsley, ” I received a message from this gentleman, asking me to call on him, explaining that he himself was confined to the house by illness. I found my host suffering, but, as was his wont, he came directly to the point. He disapproved of my ambition to occupy the civic chair — deemed it presumptuous. There was no ‘ suaviter in modo ‘ [pleasantly in manner] in the words with which he taxed me with undue pretensions, I bore with perfect equanimity the shower of sarcasms. The closing words of the conversation I well remember : ‘ You persist, then, in your wish to fill the office of mayor ? ‘ said my interlocutor. ‘ I do,’ I replied. ‘ But what then ? ‘ said my host. ‘ As a step to the representation,’ I said, boldly looking him in the face.

The alderman bounded in his chair, and striking the table with his fist, ejaculated ‘Never ! ‘ ‘What is more,’ I replied, ‘ you will vote for me when the time comes. At present I have only determined to be mayor.’ ‘ Then I suppose you must be,’ said my host. And at the next election I was made chief magistrate.”

On accepting the office, Mr. Walmsley, in his address to the council, said : ” It is well known to all of you that I have decided political opinions, and that I have always maintained these with firmness and zeal. I trust, however, I shall be able to show that I feel it to be the duty of the mayor of Liverpool to steer his course without party bias.” A few days after, he wrote to the Tradesmen’s Reform Association, resigning, not only the presidency, but the rights and privileges of membership of its body.

” It was my object,” he says, ” to unite in social gatherings the various classes and the holders of different opinions. To carry this out, I abandoned the old practice of restricting the hospitality of the town- hall to only a select few of the leading merchants, and increased the number of dinners,gave evening parties to the ladies, asked merchants and tradesmen alike, and secured that the clergy of every denomination should be mixed.”

In this genial atmosphere, men who had not spoken to one another for years became friends again; political opponents discussed each other’s views temperately; and thus a kinder feeling between the different classes of the town dated from Mr. Walmsley’s installation in office.

On the occasion of the Queen’s marriage [10 February 1840] he gave, at his own expense, a ball to one thousand two hundred persons. The ample entertainment, and the cordial welcome the chief magistrate extended alike to Radicals, Whigs, and Tories, elicited praise even from his adversaries. The most Ultra-Conservative organ testified approbation at the manner in which this thoroughgoing Radical performed his duties as mayor.

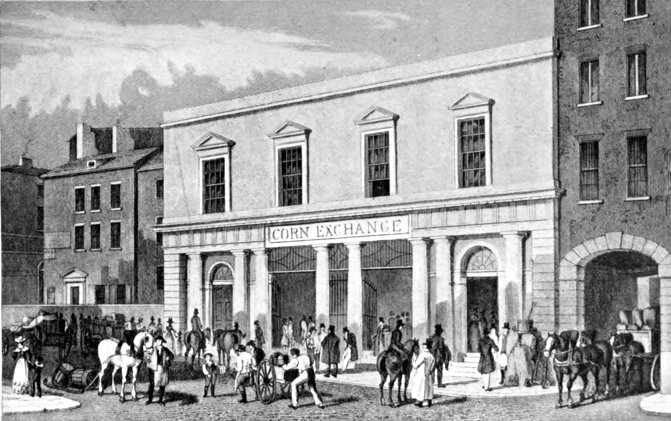

We cannot resist giving one or two of the anecdotes, scattered so brightly through the pages of notes devoted to this period. ” There lived,” writes Mr. Walmsley, ” in Liverpool a merchant, a corn-broker, a good honest-hearted fellow. He was the plainest man I ever saw — tall, ungainly, with an inveterate squint, a pair of long arms, and legs that were a match for those arms. Having a great sense of fun, he made others enjoy his ugliness ; by-the- way, he laughed at it. It happened that during my mayoralty a fancy ball was given, under the patronage of the neighbouring nobility, at the town-hall, to further the ends of charity and amusement. The ball was crowded with plebeians, and the patricians kept themselves aloof in a small room adjoining the great ball-room. The crowd did not dare cross the threshold of those sacred precincts. There were the Blundells of Crosby, the Grosvenors, the Seftons, the Derby family, and the Duchess of St. Albans.”

” This lady was of excessive embonpoint. She formed the centre of the patrician group; her brightness and gaiety, her evident enjoyment of the scene around, animated somewhat the frigid stateliness of the aristocratic party. She wore an old-fashioned costume, her skirt distended by a hoop of vast circumference, and it is no exaggeration to say that her grace’s figure did look enormous. In the course of the evening came our merchant, admirably got up as ‘Dominie Sampson.’ Nature seemed to have intended him for the part, and the manner in which he acted it excited much laughter and amusement. Presently, catching sight of the group round the Duchess of St. Albans, he strode up to it, crossed the barrier, and gazed with distended eyes at the duchess. Walking awkwardly round her, he flung his long arms aloft. ‘ Pro-di-gi-ous ! pro-di-gi-us ! ‘’ he exclaimed, shuffling away, amidst the silence of the astounded patricians. But the duchess loved a joke, and soon the mirth excited by the incident spread; the tale passed from mouth to mouth; her grace sent for ‘Dominie Sampson,’ and the ball turned out the merriest of the season.”

That year, the Eisteddfod festival was held in Liverpool ” I decided,” says Mr. Walmsley, ” to give a grand entertainment to the descendants of the Cymric bards. I consulted Archdeacon Williams, a name well known to all students of the Welsh tongue, as to the style of entertainment likely to be most agreeable to the minstrels. The archdeacon suggested that at dinner the toasts should be given out in Welsh. A slight difficulty existed — I did not know one word of the language. It was a difficulty that might be conquered, however, and I resolved to surmount it. I wrote out the lists of toasts and the speeches I purposed delivering, and the archdeacon translated them into Welsh. For three weeks, I devoted every minute I could spare to mastering these, assisted by the archdeacon.”

” The promised evening came, the table was laid out in baronial style. Harpers and minstrels were gathered together from North and South Wales in the banqueting-hall. With a flourish of trumpets, and borne by men in the beefeater’s dress, a baron of beef was carried in. The minstrels played their national airs, and around sat the representatives of the old families of the Cymri. A pause of surprise followed the first toast, given in Welsh ; but a moment after burst out a shout of enthusiasm. The compliment paid to the Principality was appreciated, and I felt my three weeks’ study had not been labour in vain. Some time after, when to me the entertainment was but a pleasant memory in the past, I was agreeably surprised on being presented, at a dinner given by the Cymreigydden Society, with a beautiful silver- mounted Hirlas horn, and a congratulatory ode in Welsh.”

Another proof of the high estimation and respect he was held in was given to Mrs. Walmsley in the shape of the public presentation to her of his full-length portrait, painted by Illidge.[ Thomas Henry Illidge (1799–1851)]. This gift was especially gratifying from the fact that the subscribers to the testimonial were chiefly persons holding opposite political views to his own. [ Rather pleasingly the portrait is now in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool]

Lord Brougham had caused Mr. Walmsley’s name to be inserted in the Commission of the Peace for the county of Lancaster and on the occasion of the Queen’s marriage, accompanied by Mr. Alderman Sheil and Mr. Councillor Bushell, he went up to London and presented the address of congratulation from the town of Liverpool. Soon after, Lord Normanby communicated to Mr. Walmsley that it was the Queen’s pleasure to confer knighthood upon him, an honour which he accepted.

At this time, it was anticipated that ere long a vacancy would occur in the representation of Liverpool. The death of the Earl of Harrowby was expected, and in this eventuality his son Lord Sandon, would be raised to the Upper House. At Liberal meetings, Sir Joshua Walmsley’s name was now frequently forward as the man best suited to represent the borough in Parliament, there to assist in the work of ameliorating the condition of the people, extending the blessings of national education, promoting free trade, and helping to break Corn-Law monopoly. The Liberals all the more openly affirmed this, seeing that the influential Whigs opposed him on the plea that his experience of public life did not justify it. The Tories, as was natural, determined to contest his election tooth and nail. The battle of conflicting opinions upon the mayor’s fitness to represent the borough was fought in the columns of the different newspapers and at public meetings.

Soon the Whigs complained that the Liberal papers refused to publish a line that might discredit Sir Joshua Walmsley’s claims. A requisition was presented to him, signed by more than half the electors of the borough, asking him to come forward as their representative at the next election. This next election was to be brought about by events nearer at hand than the death of the Earl of Harrowby.

On the 31st of October, Sir Joshua’s year of office came to a close. A vote of cordial thanks to the mayor was moved and passed by the council, acknowledging the ability, kindness, and great impartiality which he uniformly maintained in presiding over the council during the last year.

The newspapers unanimously echoed the praise the town council had bestowed upon their chief magistrate. Even the Tory papers had a good word to say. ” We cannot take a better opportunity,” says The Mail, November 10th, ” than the present of bearing our testimony, that Sir Joshua Walmsley has conducted himself during his whole mayoralty with a fairness and impartiality which reflect upon him the highest credit. He was the first reformed mayor who drew around him at his civic entertainments men of all shades of opinions. His urbanity, his well-selected parties, his desire to render his guests happy, without one taint of party feeling or invidious bias, redound to his honour, deserve to be held in remembrance, and will not soon be forgotten.”