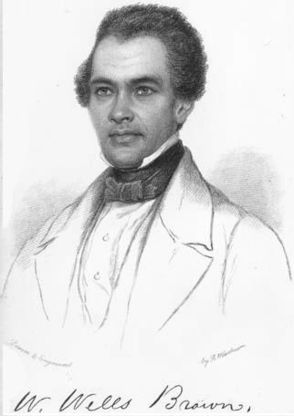

The main text in this post is Chapter XXX. from ” The American Fugitive in Europe. Sketches of Places and People Abroad. By Wm. Wells Brown.” published in Boston, Cleveland Ohio, and New York in 1855 which reprinted all of his earlier book “Three Years in Europe” with additional material up to, and including, his return to the United States. It’s an astonishing piece of writing, and all the more extraordinary for the fact that William Wells Brown was born into slavery in Kentucky in 1814, escaping to Ohio aged 20. At the time of writing, he was still potentially at risk of being returned to slavery as a result of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which ” required that all escaped slaves were, upon capture, to be returned to their masters. Brown had legally become a free man in 1854 when it had been bought by Ellen Richardson of Newcastle, England.

The choice of M.P.’s he describes is an interesting mixture. The majority he chooses could all be described as radical, pro-free trade, and in favour of greater Parliamentary reform; though there are sketches of Disraeli, Palmerston, and Gladstone, the great majority represent the newly industrialized cities of the north-west.

The House of Commons – 1854

The Abbey clock was striking nine, as we entered the House of Commons, and, giving up our ticket, were conducted to the strangers’ gallery. We immediately recognized many of the members, whom we had met in private circles or public meetings. Just imagine, reader, that we are now seated in the strangers’ gallery, looking down upon the representatives of the people of the British empire.

The Abbey clock was striking nine, as we entered the House of Commons, and, giving up our ticket, were conducted to the strangers’ gallery. We immediately recognized many of the members, whom we had met in private circles or public meetings. Just imagine, reader, that we are now seated in the strangers’ gallery, looking down upon the representatives of the people of the British empire.

There, in the centre of the room, shines the fine, open, glossy brow and speaking face of Alexander Hastie, a Glasgow merchant, a mild and amiable man, of modest deportment, liberal principles, and religious profession. He has been twice elected for the city of Glasgow, in which he resides. He once presided at a meeting for us in his own city.

On the right of the hall, from where we sit, you see that small man, with fair complexion, brown hair, gray eyes, and a most intellectual countenance. It is Layard with whom we spent a pleasant day at Hartwell Park, the princely residence of John Lee, Esq., LL.D. He was employed as consul at Bagdad, in Turkey. While there he explored the ruins of ancient Nineveh, and sent to England the Assyrian relics now in the British Museum. He is member for Aylesbury. He takes a deep interest in the Eastern question, and censures the government for their want of energy in the present war. [ The Crimean War ]

Not far from Layard you see the large frame and dusky visage of Joseph Hume. He was the son of a poor woman who sold apples in the streets of London. Mr. Hume spent his younger days in India, where he made a fortune; and then returned to England, and was elected a member of the House of Commons, where he has been ever since, with the exception of five or six years. He began political life as a tory, but soon went over to radicalism. He is a great financial reformer, and has originated many of the best measures of a practical character that have been passed in Parliament during the last thirty years. He is seventy-five years old, but still full of life and activity–capable of great endurance and incessant labor. No man enjoys to an equal extent the respect and confidence of the legislature. Though his opinions are called extreme, he contents himself with realizing, for the present, the good that is attainable. He is emphatically a progressive reformer; and the father of the House of Commons.

To the left of Mr. Hume you see a slim, thin-faced man, with spectacles, an anxious countenance, his hat on another seat before him, and in it a large paper rolled up. That is Edward Miall. He was educated for the Baptist ministry, and was called when very young to be a pastor. He relinquished his charge to become the conductor of a paper devoted to the abolition of the state church, and the complete political enfranchisement of the people. He made several unsuccessful attempts to go into Parliament, and at last succeeded Thomas Crawford in the representation of Rochdale, where in 1852 he was elected free of expense. He is one of the most democratic members of the legislature. Miall is an able writer and speaker–a very close and correct reasoner. He stands at the very head of the Nonconformist party in Great Britain; and The Nonconformist, of which he is editor, is the most radical journal in the United Kingdom.

Look at that short, thick-set man, with his hair parted on the crown of his head, a high and expansive forehead, and an uncommon bright eye. That is William Johnson Fox. He was a working weaver at Norwich; then went to Holton College, London, to be educated for the Orthodox Congregational ministry; afterwards embraced Unitarian views. He was invited to Finsbury Chapel, where for many years he lectured weekly upon a wide range of subjects, embracing literature, political science, theology, government and social economy. He is the writer of the articles signed “Publicola,” in the Weekly Dispatch, a democratic newspaper. He has retired from his pulpit occupations, and supports himself exclusively by his pen, in connection with the liberal journals of the metropolis. Mr. Fox is a witty and vigorous writer, an animated and brilliant orator.

Yonder, on the right of us, sits Richard Cobden. Look at his thin, pale face, and spare-made frame. He started as a commercial traveller; was afterwards a calico-printer and merchant in Manchester. He was the expounder, in the Manchester Chamber of Commerce and in the town council, of the principles of free trade. In the council of the Anti-Corn-Law League, he was the leader, and principal agitator of the question in public meetings throughout the kingdom. He was first elected for Stockport. When Sir Robert Peel’s administration abolished the corn-laws, the prime minister avowed in the House of Commons that the great measure was in most part achieved by the unadorned eloquence of Richard Cobden. He is the representative of the non-intervention or political peace party; holding the right and duty of national defence, but opposing all alliances which are calculated to embroil the country in the affairs of other nations. His age is about fifty. He represents the largest constituency in the kingdom–the western division of Yorkshire, which contains thirty-seven thousand voters. Mr. Cobden has a reflective cast of mind; and is severely logical in his style, and very lucid in the treatment of his subjects. He may be termed the leader of the radical party in the House.

Three seats from Cobden you see that short, stout person, with his high head, large, round face, good-sized eyes. It is Macaulay, the poet, critic, historian and statesman. If you have not read his Essay on Milton, you should do so immediately; it is the finest thing of the kind in the language. Then there is his criticism on the Rev. R. Montgomery. Macaulay will never be forgiven by the divine for that onslaught upon his poetical reputation. That review did more to keep the reverend poet’s works on the publisher’s shelves than all other criticisms combined. Macaulay represents the city of Edinburgh.

Look at that tall man, apparently near seventy, with front teeth gone. That is Joseph Brotherton, the member for Salford. He has represented that constituency ever since 1832. He has always been a consistent liberal, and is a man of business. He is no orator, and seldom speaks, unless in favour of the adjournment of the House when the hour of midnight has arrived. At the commencement of every new session of Parliament he prepares a resolution that no business shall be entered upon after the hour of twelve at night, but has never been able to carry it. He is a teetotaller and a vegetarian, a member of the Peace Society, and a preacher in the small religious society to which he belongs.

In a seat behind Brotherton you see a young-looking man, with neat figure, white vest, frilled shirt, with gold studs, gold breast-pin, a gold chain round the neck, white kid glove on the right hand, the left bare with the exception of two gold rings. It is Samuel Morton Peto. He is of humble origin–has made a vast fortune as a builder and contractor for docks and railways. He is a Baptist, and contributes very largely to his own and other dissenting denominations. He has built several Baptist chapels in London and elsewhere. His appearance is that of a gentleman; and his style of speaking, though not elegant, yet pleasing.

Over on the same side with the liberals sits John Bright, the Quaker statesman, and leader of the Manchester school. He is the son of a Rochdale manufacturer, and first distinguished himself as an agitator in favour of the repeal of the corn-laws. He represents the city of Manchester, and has risen very rapidly. Mr. Cobden and he invariably act together, and will, doubtless, sooner or later, come into power together. Look at his robust and powerful frame, round and pleasing face. He is but little more than forty; an earnest and eloquent speaker, and commands the fixed attention of his audience.

See that exceedingly good-looking man just taking his seat. It is William Ewart Gladstone. He is the son of a Liverpool merchant, and represents the University of Oxford. He came into Parliament in 1832, under the auspices of the tory Duke of Newcastle. He was a disciple of the first Sir R. Peel, and was by that statesman introduced into official life. He has been Vice-president and President of the Board of Trade, and is now Chancellor of the Exchequer. Mr. Gladstone is only forty-four. When not engaged in speaking he is of rather unprepossessing appearance. His forehead appears low, but his eye is bright and penetrating. He is one of the ablest debaters in the House, and is master of a style of eloquence in which he is quite un-approached. As a reasoner he is subtle, and occasionally jesuitical; but, with a good cause and a conviction of the right, he rises to a lofty pitch of oratory, and may be termed the Wendell Phillips of the House of Commons.

There sits Disraeli, amongst the Tories. Look at that Jewish face, those dark ringlets hanging round that marble brow. When on his feet he has a cat-like, stealthy step; always looks on the ground when walking. He is the son of the well-known author of the “Curiosities of Literature.” His ancestors were Venetian Jews. He was himself born a Jew, and was initiated into the Hebrew faith. Subsequently he embraced Christianity. His literary works are numerous, consisting entirely of novels, with the exception of a biography of the late Lord George Bentinck, the leader of the protectionist party, to whose post Mr. Disraeli succeeded on the death of his friend and political chief. Mr. Disraeli has been all round the compass in politics. He is now professedly a conservative, but is believed to be willing to support any measures, however sweeping and democratical, if by so doing he could gratify his ambition–which is for office and power. He was the great thorn in the side of the late Sir R. Peel, and was never so much at home as when he could find a flaw in that distinguished statesman’s political acts. He is an able debater and a finished orator, and in his speeches wrings applause even from his political opponents.

Cast your eyes to the opposite side of the House, and take a good view of that venerable man, full of years, just rising from his seat. See how erect he stands; he is above seventy years of age, and yet he does not seem to be forty. That is Lord Palmerston. Next to Joseph Hume, he is the oldest member in the House. He has been longer in office than any other living man. All parties have, by turns, claimed him, and he has belonged to all kinds of administrations; tory, conservative, whig, and coalition. He is a ready debater, and is a general favorite, as a speaker, for his wit and adroitness, but little trusted by any party as a statesman. His talents have secured him office, as he is useful as a minister, and dangerous as an opponent.

That is Lord Dudley Coutts Stuart speaking to Mr. Ewart. His lordship represents the populous and wealthy division of the district of Marylebone. He is a radical, the warm friend of the cause of Poland, Hungary and Turkey. He speaks often, but always with a degree of hesitation which makes it painful to listen to him. His solid frame, strongly-marked features, and unmercifully long eye-brows are in strange contrast to the delicate face of Mr. Ewart.The latter is the representative for Dumfries, a Scotch borough. He belongs to a wealthy family, that has made its fortune by commerce. Mr. Ewart is a radical, a staunch advocate of the abolition of capital punishment, and a strenuous supporter of all measures for the intellectual improvement of the people.

Ah! we shall now have a speech. See that little man rising from his seat; look at his thin black hair, how it seems to stand up; hear that weak, but distinct voice. O, how he repeats the ends of his sentences! It is Lord John Russell, the leader of the present administration. He is now asking for three million pounds sterling to carry on the war. He is a terse and perspicuous speaker, but avoids prolixity. He is much respected on both sides of the House. Though favourable to reform measures generally, he is nevertheless an upholder of aristocracy, and stands at the head and firmly by his order. He is brother to the present Duke of Bedford, and has twice been Premier; and, though on the sunny side of sixty, he has been in office, at different times, more than thirty years. He is a constitutional whig and conservative reformer. See how earnestly he speaks, and keeps his eyes on Disraeli! He is afraid of the Jew. Now he scratches the bald place on his head, and then opens that huge roll of paper, and looks over towards Lord Palmerston.

That full-faced, well-built man, with handsome countenance, just behind him, is Sir Joshua Walmsley. He is about the same age of Lord John; and is the representative for Leicester. He is a native of Liverpool, where for some years he was a poor teacher, but afterwards became wealthy in the corn trade. When mayor of his native town, he was knighted. He is a radical reformer, and always votes on the right side.

Lord John Russell has finished and taken his seat. Joseph Hume is up. He goes into figures; he is the arithmetician of the House of Commons. Mr. Hume is in the Commons what James N. Buffum is in our Anti-Slavery meetings, the man of facts. Watch the old man’s eye as he looks over his papers. He is of no religious faith, and said, a short time since, that the world would be better off if all creeds were swept into the Thames. His motto is that of Pope:

“For modes of faith let graceless zealots fight:

His can’t be wrong whose life is in the right.”

Mr. Hume has not been tedious; he is done. Now for Disraeli. He is going to pick Lord John’s speech to pieces, and he can do it better than any other man in the House. See how his ringlets shake as he gesticulates! and that sarcastic smile! He thinks the government has not been vigorous enough in its prosecution of the war. He finds fault with the inactivity of the Baltic fleet; the allied army has made no movement to suit him. The Jew looks over towards Lord John, and then makes a good hit. Lord John shakes his head; Disraeli has touched a tender point, and he smiles as the minister turns on his seat. The Jew is delighted beyond measure. “The Noble Lord shakes his head; am I to understand that he did not say what I have just repeated?” Lord John: “The Right Hon. Gentleman is mistaken; I did not say what he has attributed to me.” Disraeli: “I am glad that the Noble Lord has denied what I thought he had said.” An attack is made on another part of the minister’s speech. Lord John shakes his head again. “Does the Noble Lord deny that, too?” Lord John: “No, I don’t, but your criticism is unjust.” Disraeli smiles again: he has the minister in his hands, and he shakes him well before he lots him go. What cares he for justice? Criticism is his forte; it was that that made him what he is in the House. The Jew concludes his speech amid considerable applause.

All eyes are turned towards the seat of the Chancellor of the Exchequer: a pause of a moment’s duration, and the orator of the House rises to his feet. Those who have been reading The Times lay it down; all whispering stops, and the attention of the members is directed to Gladstone, as he begins. Disraeli rests his chin upon his hat, which lies upon his knee: he too is chained to his seat by the fascinating eloquence of the man of letters. Thunders of applause follow, in which all join but the Jew. Disraeli changes his position on his seat, first one leg crossed, and then the other, but he never smiles while his opponent is speaking. He sits like one of those marble figures in the British Museum. Disraeli has furnished more fun for Punch than any other man in the empire. When it was resolved to have a portrait of the late Sir R. Peel painted for the government, Mr. Gladstone ordered it to be taken from one that appeared in Punch during the lifetime of that great statesman. This was indeed a compliment to the sheet of fun. But now look at the Chancellor of the Exchequer. He is in the midst of his masterly speech, and silence reigns throughout the House.

“His words of learned length and thundering sound

Amazed the gazing rustics ranged around;

And still they gazed, and still the wonder grew

That one small head could carry all he knew.”

Let us turn for a moment to the gallery in which we are seated. It is now near the hour of twelve at night. The question before the House is an interesting one, and has called together many distinguished persons as visitors. There sits the Hon. and Rev. Baptist W. Noel. He is one of the first of the Nonconformist ministers in the kingdom. He is about fifty years of age; very tall, and stands erect; has a fine figure, complexion fair, face long and rather pale, eyes blue and deeply set. He looks every inch the gentleman. Near by Mr. Noel you see the Rev. John Cumming, D.D. We stood more than an hour last Sunday in his chapel in Crown-court to hear him preach; and such a sermon we have seldom ever heard. Dr. Cumming does not look old. He has rather a bronzed complexion, with dark hair, eyes covered with spectacles. He is an eloquent man, and seems to be on good terms with himself. He is the most ultra Protestant we have ever heard, and hates Rome with a perfect vengeance. Few men are more popular in an Exeter Hall meeting than Dr. Cumming. He is a most prolific writer; scarce a month passes by without something from his pen. But they are mostly works of a sectarian character, and cannot be of long or of lasting reputation.

Further along sits a man still more eloquent than Dr. Cumming. He is of dark complexion, black hair, light blue eyes, an intellectual countenance, and when standing looks tall. It is the Rev. Henry Melville. He is considered the finest preacher in the Church of England. There, too, is Washington Wilks, Esq., author of “The Half-century.” His face is so covered with beard that I will not attempt a description; it may, however, be said that he has literally entered into the Beard Movement.

Come, it is time for us to leave the House of Commons. Stop a moment! Ah! there is one that I have not pointed out to you. Yonder he sits amongst the tories. It is Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, the renowned novelist. Look at his trim, neat figure; his hair done up in the most approved manner; his clothes cut in the latest fashion. He has been in Parliament twenty-five years. Until the abolition of the corn-laws, he was a liberal; but as a land-owner he was opposed to free trade, and joined the protectionists. He has two country-seats, and lives in a style of oriental magnificence that is not equalled by any other man in the kingdom; and often gathers around him the brightest spirits of the age, and presses them into the service of his private theatre, of which he is very fond. In the House of Commons he is seldom heard, but is always listened to with profound attention when he rises to speak. He labors under the disadvantage of partial deafness. He is undoubtedly a man of refined taste, and pays a greater attention to the art of dress than any other public character I have ever seen. He has a splendid fortune, and his income from the labors of his pen is very great. His title was given to him by the queen, and his rank as a baronet he owes to his high literary attainments. Now take a farewell view of this assembly of senators. You may go to other climes, and look upon the representatives of other nations, but you will never see the like again.