A Serjeant-at-Law (SL), commonly known simply as a Serjeant, was a member of an order of barristers at the English bar. The Serjeants were the oldest formally created order in England, having been brought into existence as a body by Henry II. There were rarely more than 40 Serjeants. The Judicature Act 1873, removed the need for common law judges to be appointed from the Serjeants-at-Law, removing the need to appoint judicial Serjeants. With this Act and the rise of the Queen’s Counsel, there was no longer any need to appoint Serjeants, and the order ceased after seven hundred years.

MEMORIALS OF MR. SERJEANT BELLASIS.

The lives of men who have lived well, or fought well, or studied well, must always possess some interest for the student of human nature. Their struggles are probably akin to his struggles, their joys and sorrows are identical. In all creative and dramatic art, as in all literature, the human element is the centre of interest, —the actors on life’s stage command our deepest attention.

Light has been shed broadly and powerfully on all the leaders of the great Oxford movement. Their motives and main-springs of action have been analysed and dissected until little is left to analyse or dissect. The battle-field is still whitened with innumerable relics of a doubtful battle. Profoundly interesting as were those times, and profoundly momentous the issues of them, it seems hardly possible to learn anything fresh about them. ” Tracts for the Times, “ “No. 90, “ the Gorham decision, the Anglo-Prussian bishopric, the Anglican succession,—it is inevitable that all biographers of men who lived in those times should describe the same well- known facts and repeat the same well-worn phrases. There seems hardly space for another biography of an individual who played a part, though a comparatively small one, in a movement of which Dean Church and Mr. W. Ward have so lately recounted to us the principal events, giving us such brilliant portraits of the principal actors.

In the preface to this Memoir of the late Mr. Serjeant Bellasis, we read:— ” It has been deemed that some notice of Mr. Serjeant Bellasis, beyond the two or three columns in the National Dictionary of Biography, would not be out of place among the memoirs of the time ; for the late Serjeant, although not one of the more conspicuous public men of his day, nevertheless played some part in the Tractarian Movement of 1833, in connection wherewith he has left papers of interest. He was also an able and, for nearly a quarter of a century, a notable member of the Catholic body. “

The Serjeant’s early life and legal career are dismissed in the first chapter ; the rest of the volume is chiefly taken up with theological arguments and writings on the questions of the day, and letters from well-known people. Some of these letters have already appeared in Mr. R. Ornsby’s Memoir of James Hope-Scott. Edward Bellasis was born in 1800 at Basilden, a pretty village on the Thames, of which his father was the vicar. Dr. Bellasis died when his son was an infant, and shortly afterwards his widow married the Rev. Joseph Maude, a Low Churchman, whose intimate friends were chiefly Quakers and Evangelicals. The household was taught to pray against ” the machinations of Popery “ and the ” devices of the Bishop of Rome ; “ card-playing and theatre-going were forbidden. In spite of this prohibition, young Bellasis went to Drury Lane, and there ran against his step-father’s brother, the Rev. John Maude, in the pit, who remarked,—” If you tell of me, I’ll tell of you. “ He seems to have had a love of play-going all his life, and to have encouraged private theatricals in his children’s holidays. He was called to the Bar in 1824, and began a long and very successful career, being almost exclusively employed in Parliamentary business, often connected with railways, until his retirement in 1866. There is a graphic account of his receiving the ” degree of the Coif “ and the ancient forms and ceremonies attending the creation of a Serjeant-at-Law. His intimate friend, Mr. Badeley, was his ” colt, “ and presented the rings to the Lord Chancellor and the Judges. The Queen’s ring was ” large and massive enough to cover two joints of the finger. “ In conjunction with Mr. Hope-Scott, the Serjeant was appointed trustee of the Shrewsbury estates, a duty that both fulfilled with characteristic disinterestedness and high principle. ” There was a great deal in common in the dear Serjeant and Hope-Scott, “ wrote Dr. Newman; ” This similarity is what made them such great friends. “ The history of one is in great measure a counterpart of that of the other. Both were distinguished members of the Bar, both followed the Anglican revival with the greatest interest, finally both joined the Church of Rome, Bellasis in 1850, Hope-Scott in 1851, and Badeley, the third point in this friendly triangle, in 1852. When the news of the conversion [of Mr. Serjeant Bellasis] reached Quernmore Park, the residence of Mr. Garnett,[his father-in-law] Mrs. Bellasis’ aunt, Miss Carson, as a sincere Evangelical, was naturally much distressed, and the old family cook, seeing her mistress in tears, inquired the cause. ‘ Mr. Bellasis had gone over to Rome.’ Ah ! ‘ replied the cook, ” tis a pity. Isn’t it very cold there ? Hard nigh upon Rooshee, rye heard tell.’ “ Mr. Bellasis seems always to have had an inquiring mind in regard to religious matters, and to have started in life with a decided bias against ” Popery.” A visit to a Roman Catholic chapel in Moorfields in 1820 only ” impresses him with the superiority of the reformed Protestant religion. “ However, foreign travel corrected many of his ideas about the Roman Catholics. He notes the earnestness of the people at their prayers, and the admixture of devout observances with their ordinary daily occupations. He came home still a ” thorough Anglican,” but he could neither abuse, nor listen to abuse, of Catholicsor Catholicism. After his second marriage in 1835, Mr. Bellasis took a house in Bedford Square, and then began the intimacy with Mr. Oakeley, of Margaret Street Chapel, in whose footsteps, in religious matters, the Serjeant closely followed. Mr. Oakeley gave him letters of introduction to some of the most prominent leaders of the Oxford movement,—Newman, W. G. Ward, and J. B. Morris. He made several visits to Oxford, and got to know Hope-Scott, Badeley, Dr. Pusey, and Bounden Palmer ; he also stayed with the Yonges at Otterbourne, and met Keble and Wilberforce. ” We have had a rather pleasant, interesting man visiting us,” writes Canon James Mozley to his sister in January, 1840, ” a Mr. Bellasis, a barrister from London, very High Church, a friend of Ward of Balliol, who happens to be away just now, Newman and others have entertained him. It is amusing to see the variety of a Londoner in Oxford. Of the London element lie retains enough to make a change from what one commonly sees here ; though with none of the disagreeable features of it,—for example, he is so much more fluent, and can give regular narrations with spirit, showing a person who has been accustomed to argue and make speeches. “ In one of the Serjeant’s letters to his wife, there is a graphic account of Newman’s farewell sermon at Littlemore; he used to say afterwards that there was not a dry eye in the church, except Newman’s own. In 1845 the Serjeant wrote to his brother, ” I do not conceal from any one that I hold what you call ultra opinions; “ but he goes on to say, ” it has never occurred to me that it is the duty of persons holding such opinions to quit the Church of England. “ He had, however, thought much on the subject, as we read in the Memoir :—” The Serjeant himself had painfully gone through all stages, from Low Evangelicism to extreme High Churchmanship, until at length the time came when he found little of real difficulty in any Catholic doctrine. This is sufficiently illustrated, some time before his actual conversion, by a little paper of September, 1847, referring to Confession, perhaps a greater stumbling- block to Protestants inclined to Catholicism than anything else after Papal supremacy. “ The Serjeant was accustomed to weigh difficult questions, and to analyse the balance of evidence ; his excessive pains to get at the exact truth of Catholicism abroad gave Dr. Scholl, of Treves [Trier], the idea that he was too cautious ever to leave his own Church. “Ala, ce pauvre Monsieur Bellasis, it a taut de scrupules ; it n’entrera janmis dans l’Eglise.” Outward and visible signs and symbols. always attracted him—” believing himself to be a man without much sentiment or feeling, he said that he relied greatly upon externals in religion “—and he was always most exact in all outward observances. Much is said of his great industry and power of concentration. He writes of himself,—” It is my nature to be eager in whatever I take up, whether it is meteorology, geology, theology, or business ; “ but no recreation was ever allowed to interfere with business. His family life seems to have been particularly happy ; he was devoted to his children, and drew up many wise rules of conduct for their instruction, which are worth reading and copying. With one daughter, afterwards a nun, he kept up a playful warfare as to the amount of their mutual love. In 1871, he wrote to her:—” I have got a puzzle for you : St. Alphonsus says that of all love, paternal love is the strongest; now I think I have checkmated you.” There are many instances told of his unvarying kindness and courtesy to strangers, and to any one who served him or needed his help. Mr. Hope-Scott’s clerk, who saw him every day, said he never once knew the Serjeant ruffled or disturbed, and never heard him utter a harsh or unkind word. ” He died at Hyéres,” wrote his friend, Hope-Scott, during his own last illness, “l eaving an example to us all,” and Archbishop Manning and Dr. Newman echoed the words.

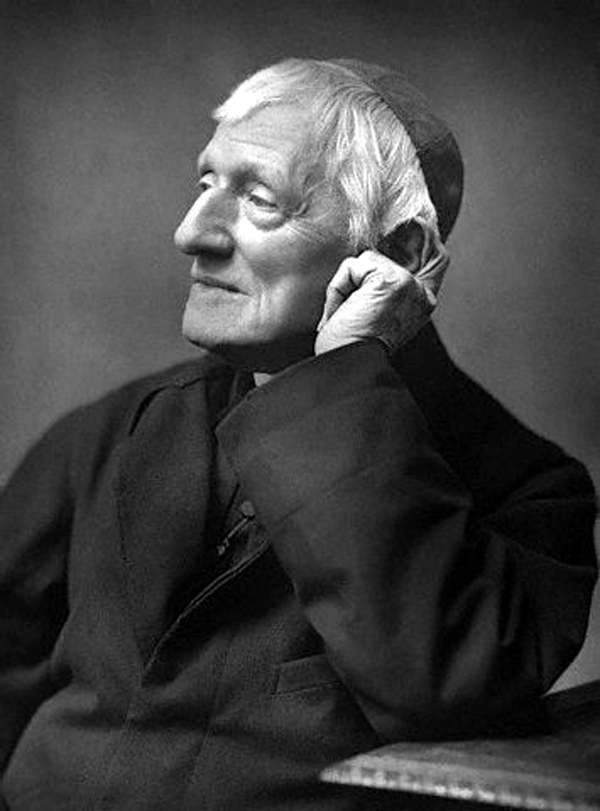

Such a life as the Serjeant’s does not contain much of deep interest to the general reader. His contributions to the literature of the day consisted of a few pamphlets, and the Memoir is naturally written from a devout Roman Catholic point of view ; but the surroundings of his life were interesting, and he was intimate with men whose names are written in Church history. It was probably Dr. Newman’s example and influence that finally led the Serjeant to abandon the Church of England. As Sir Francis Doyle has written,—” That great man’s ardent zeal and extraordinary genius drew all those within his sphere, like a magnet, to attach themselves to him and his doctrine.”

From The Spectator 5 August 1893, Page 18