This is largely taken from Chapter IV. of Tom Burke’s ” Catholic History of Liverpool “, 1910. He is not a disinterested party. He was Liverpool born and bred, with Irish parents. He was for many years, a magistrate, councillor, and Alderman on Liverpool City Council where he represented Vauxhall ward as a member of the Irish Nationalist Party. Liverpool Scotland constituency, which Vauxhall was part of, returned T.P. O’Connor as an Irish Party M.P. for 44 years between 1885 and 1929, the only constituency outside Ireland ever to return an Irish Nationalist Party MP. None of this really detracts from the power of Tom Burke’s writing. The rest of the post of his with the original footnotes from the book bracketed, and in italics, along with a couple of additional explanations of mine also in bracketed italics.

Over to Alderman Burke:

A dark cloud fell upon Liverpool in the last months of the year [1846], and when it passed away, a new Catholic Liverpool arose, with new problems and fresh difficulties, many of which are not yet solved. No man can understand aright the Liverpool of the second half of the nineteenth century, who does not seriously study the dread incidents which the November and December portended.

From the point of view of public health, Liverpool had degenerated into one of the worst towns in the Kingdom. Narrow streets, narrower courts, overcrowded alleys, and bad drainage, were exacting a heavy toll of disease and death. Streets were left unswept for as long a period as three weeks, in working class quarters, the Town Council being much too busy with the interests of party to occupy itself with such mundane affairs. The Tories were blind to all warnings; in capturing the Council Schools they had exhausted their mandate. To promote sanitary reform, a Health of Towns Association had been formed in the Metropolis, and the first Liverpool branch was founded in St. Patrick’s schoolroom.

Just as, half-a-century later, it was reserved for Liverpool Catholic public men to fight the battle of housing reform, so in the early forties it was left for the Catholic leaders to speak out against the criminal neglect, by the Corporation, of the important question of public health. Sir Arnold Knight, M.D., father of a future Bishop of Shrewsbury, and of a distinguished Jesuit, delivered the address at this gathering, presided over by Mr. R. Sheil. His speech is painful reading, descriptive of the conditions under which the labouring classes were compelled to live, conditions which made moral or physical health well-nigh impossible. Sir Arnold stated, that in London one out of every thirty-seven of the population died annually; Liverpool’s proportion being one in twenty- eight. In the Metropolis, 32 out of every 100 children died before reaching the age of nine ; Liverpool had the unenviable record of 49. Nor was this all. In the densely populated streets and courts of Vauxhall Ward, this number went up to 64, an appalling rate of mortality. Physical deterioration had set in, or, as the Catholic Knight put it, Liverpool men “were unfit to be shot at “, an allusion to the rejection of 75 per cent of the recruits for the army.

This speech gives the answer to much of the superficial criticism of the result of Irish ” habits “ on the general health of towns. The death roll gives the needed and only reply to the puzzle which has worried Catholic statisticians as to the causes which have operated to prevent the prolific Irish from being one-half, at least, of the population of Liverpool. Sixty- four out of every hundred Irish children dead before nine years of age, from preventible causes ! !

The Irish poor did not build the narrow streets nor the dirty courts, they did not leave the streets unswept, and had no responsibility for stinking middens, left unemptied at their very doors, nor did they create the economic conditions which drove them across the channel, and in turn made life in Liverpool the burden it really was. Drink ! Yes, they drank ! No wonder ! where drink alone could bring forgetfulness of present misery. But for the small band of priests who laboured amongst them, and the faith they brought from Ireland, Irish Liverpool had become heathendom. The demoralisation of child life caused by exclusion from the schools, in 1841, had sown its seeds, and a deadly harvest was to be reaped a generation later, which, even to the twentieth century, has made Liverpool a bye-word to every stranger entering its gates.

It was too late for any body of men to cure the evil, when the famine years sent hundreds of thousands of Irishmen and women into the very streets and alleys, where over-crowding and disease had become every-day features, and excited no surprise. The closing months of 1846 ended in ” an inpouring of wretchedness from Ireland; streets swarming with hungry and almost naked wretches.” Written by a friendly hand, these words fail to convey an adequate picture of the scenes witnessed every day during November and December, 1846.

At the meeting of the Select Vestry,[the official title of the Liverpool Board of Poor Law Guardians] December 15th, 1846, the captains of the coasting vessels were censured for carrying over such large numbers of immigrants, and it was seriously suggested that Liverpool should follow the example of the Isle of Man authorities, by refusing permission to land. It is pleasant to record that the first meeting held to raise funds for the relief of the famine stricken, was organised by the Irish navvies, then constructing the railway to Bury. The meeting was held in the schoolroom underneath St. Joseph’s chapel, Grosvenor Street, on November 30th, every navvy putting down one day’s wages on the table as his tribute to the unfortunate people of his own country. In the church, the first sermon for the same object was preached by Father McEvoy, parish priest of Kells, in the fertile plains of Meath, who received fifty-two pounds from the poor labourers of St. Joseph’s parish. The new year, 1847, opened inauspiciously. During the six days, January 4th to 9th, the Select Vestry relieved 7,146 Irish families, consisting of 29,417 persons, of whom 18,376 were children.

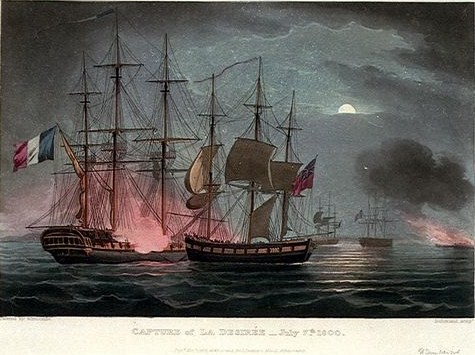

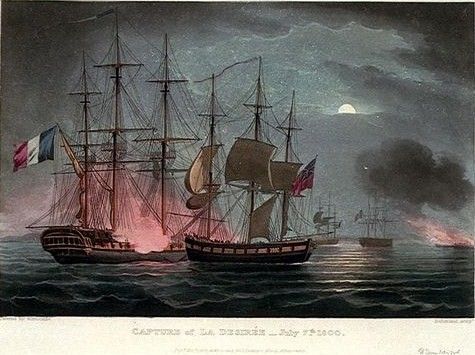

From the 13th to the 25th of the same month, 10,724 deck passengers arrived from Irish ports, and during the month of February they came pouring in at the average rate of nine hundred per day. So dreadful was their poverty that we have the authority of the Rector of Liverpool, speaking on the 26th of February, that nine thousand Irish families were being relieved, a number which increased to eleven thousand by the end of March. The Stipendiary Magistrate had given an instruction to the police to keep a record of the number of immigrants, and, at a meeting of the justices summoned by him to consider suitable measures to cope with this serious menace to health and peace, he stated that, from the first day of November, 1846, to the twelfth day of May, 1847, the total number of Irish immigrants into Liverpool amounted to 196,338. Deducting the numbers actually recorded as sailing to America, no less than 137,519 persons had been added to the population of Liverpool. When the year ended, the total number of immigrants, excluding those who were bound for America, reached the immense total of 296,231, all ” apparently paupers.” [Head Constable Dowling’s Report to the Watch Committee.]

The already overcrowded Irish quarters gave some kind of shelter to the new comers ; its character makes the heart sick, even when read in cold print. No less than 35,000 were housed in cellars, [ Liverpool Mercury, 1847.] below the level of the street, without light or ventilation; 5841 cellars [Gore’s Annals of Liverpool.] were ” wells of stagnant water “ or, as an official report to the Corporation puts it, 5,869 were found, on examination, to be ” damp, wet, or filthy.” In the district now known as Holy Cross parish, not then formed, and in St. Vincent’s, an appalling state of affairs prevailed. In Lace Street, Marybone, in a cellar 14 feet long, ten wide, and six in height, twelve persons were found endeavouring to breathe, and, ” in more than one instance, upwards of forty people were found sleeping “ in a similar underground dungeon. [Medical Officer s Report for 1847. W. H. Duncan, M.D. ] The Stipendiary shocked the town by his narrative of a woman being confined of twins, in a Lace Street cellar, crowded with human beings. In Crosby Street, Park Lane, now occupied by the Wapping Goods Station, of the L. & N. W. Railway Company, 37 people were found in one cellar, and in another eight lay dead from typhus.

The unfortunates ” occupied every nook and corner of the already over-crowded lodging houses, and forced their way into the cellars (about 3,000 in number), which had been closed under the Health Act of 1842. In different parts of Liverpool, fifty or sixty of these destitute people were found in a house containing three or four small rooms, about twelve feet by ten.” [Head Constable Dowling’s Report to the Watch Committee.] By February, the mortality from fever was eighteen per cent, above the average, and four months later was 2,000 per cent. above the average of previous years.[ W. H. Duncan, M.D. Report to the Health Committee, 1847.]

Smallpox broke out and carried off 381 children, and an epidemic of measles added 378 to the total. In Lace Street, already mentioned, one-third of the inhabitants, that is to say 472 persons, died from fever during the year. In the Parish of Liverpool, the weekly mortality by the month of August reached 537, as against the usual average of 160 ; while in the extra parochial districts of Toxteth and Everton, it was 111 against 50. The curse of mis-rule in Ireland, and mis-government in Liverpool, had come home to roost, and he who would pass judgment on Irish poverty or “crime “ of later years, let him read the story which every stone of the charnel houses in Vauxhall, Exchange, Scotland, Great George and Pitt Street Wards, told and still tell. Here were sown the dragon’s teeth, and they have sprung up, not in armed men, but workhouses, reformatories, and gaols.

Regulations of all kinds were brought into force to put a much-needed check on this enormous influx, but without avail for at least a year. The Poor Law authorities returned 24,529 to their native parishes during the years 1847 and 1848 ; [See Dr. Mackay’s article on Liverpool in Morning Chronicle.] it was only a drop in the ocean, for vessels were arriving daily with fresh contingents. Deck passages from Dublin cost as small a sum as sixpence, which probably tempted thousands to try their fortune in our midst. It stands to the infinite credit of the citizens that distinctions of race, religion, and party were obliterated in presence of this awful visitation, and that they united to succour the sick and hungry, both in the town and the country from whence they came. There were two exceptions, which only served to bring out this noble generosity in strong relief.

Vestryman Mellor gleefully exclaimed, at a meeting of the Select Vestry, ” when they are all gone, we will people Ireland with a better set,” and Dr. Hugh McNeill [ vicar of St Jude’s, and later St Paul’s, Princes Park, Liverpool (1834-1848), and a virulently anti-Catholic preacher,] characteristically accused the Irish clergy of refusing to dispense the English Relief Funds, unless the recipients paid them a consideration. These men were the sole exceptions to the truly Christian spirit which prevailed in all classes. Bishop Sharples acted with commendable promptitude. Summoning a meeting of Catholics in the Concert Hall, Lord Nelson Street, he had the pleasure of receiving two thousand pounds from his flock in the course of a few minutes. This sum was subscribed by less than fifty persons, and was dispatched next day by the treasurer, Mr. C. J. Corbally, in equal shares to the Archbishops of Cashel and Tuam. Church collections were immediately taken, and one thousand pounds came from this source; St. Patrick s heading the list with £ 118 16s. 7d., a few shillings more than the amount subscribed by St. Nicholas .

A name never to be forgotten in the annals of Liverpool Catholicism appeared for the first time in print, in connection with the famine fund, that of a young priest, Father James Nugent, who preached at St. Alban’s, Blackburn, and handed £ 72 12s. 8d. to the Liverpool treasurer. It was related by the journals of the day, that the Post Office was besieged by Irish labourers, sending small sums of money home to their afflicted kinsfolk. The condition of Ireland was bad, but it may well be doubted whether that of Liverpool was not worse. Where were the mass of new-comers to be housed? Where was employment to be found? Whence could be drawn clergy to come to attend to their spiritual needs? If church and school accommodation was deficient before 1847, it was surely deficient now.

In January, 1847, the Rector of Liverpool informed the Government that dysentery had assumed alarming proportions, due to the cabbages and turnips which formed the only food of the first immigrants. February saw eight hundred cases of typhoid ; the reading of the death-roll each Sunday morning in the churches sending a cold shiver through the immense congregations. Hurriedly the parish authorities set up fever sheds, in Great Homer Street on the North, and Mount Pleasant on the South, and fitted up a hospital ship in the Mersey, to cope with the new terror. Then came the awful visitation of typhus. Liverpool Protestantism bowed its head in reverence at the heroism of the handful of Catholic Priests.

Undaunted, they went from room to room in crowded houses ; from cellar to garret, ministering to the sick. They were never absent from hourly attendance in the hospital wards. Here at least there was some privacy, but in the crowded rooms and cellars it was next to impossible to hear the last confession, unless the priest lay down beside the sick man to receive the seeds of disease from poisoned breaths in return for spiritual consolations. In very truth they were braver men than ever faced the lions in a Roman amphitheatre.

If life must be sacrificed, it were fitting that St. Patrick’s should provide the first victim. Father Parker, rector for seventeen years, succumbed to typhus on April 28th, aged 43, [Buried in the vaults of the church. Dr. Youens sang the Requiem; the sub-deacon was Father Nugent] and was followed on May 26th by the scholarly Benedictine, Dr. Appleton, of St. Peter’s, who exchanged the Presidency of Douai College for a martyr s crown, won in the pestilential cellars of Crosby Street. The fine sanctuary of the church recalls his last work for the oldest ecclesiastical building in Liverpool, and the tablet on the walls of the church reminds succeeding generations of his great charity. St. Patrick’s again rendered two more victims, Father Grayston succumbing on the 16th June, aged 33, and his colleague, Father Haggar, [ Died at the house of Mr. Denis Madden, 116, Islington.] aged 29, following him seven days later. A third priest who had left the plains of Westmeath to work among his people in England, the Rev. Bernard O Reilly, was also stricken down. The rector of Old Swan, Father, afterwards Canon, Haddocks, took him from the presbytery at Saint Patrick’s to his own house, in the country, where he recovered in a most miraculous manner, and lived to become the third Bishop of Liverpool. St. Mary’s then took up the beadroll of death ; Father Gilbert, O.S.B., aged 27, and Father William Dale, O.S.B., aged 43, succumbing to typhus on the 31st May and 28th June respectively.

On the 22nd August, Father Richard Gillow, [He founded the St, Vincent de Paul Conference at St. Nicholas.] a member of a most devoted Catholic family, yielded up his young life he was but 36 years of age at St. Nicholas , and on the 28th September, the death of Father Whitaker, at St. Joseph’s, completed the death-roll for the year. Father Whitaker’s career was unique. He entered Douai with the intention of becoming a Benedictine, and after some years abandoned his undoubted vocation for the study of medicine. On the eve of qualifying he changed his mind and resumed his ecclesiastical studies at St. Sulpice, Paris. From thence he proceeded to Ushaw, where he was ordained, and after serving on the mission at Bolton, York, and Manchester, found an early grave in the slums of Liverpool. The deaths of these priests; [ To these should be added Father Nightingale, who died March 2nd, and Father Thomas Kelly, D.D,, who died May 1st.] made a profound impression on a town which had witnessed 15,000 deaths from famine and fever, and exalted in the estimation of the Protestant citizens the character and dignity of the priesthood. The strain on the surviving clergy, most of whom suffered severely, was intense. They lay at night on chairs and sofas in their clothes, awaiting the sick calls which never failed to come, fearful lest the time spent in dressing might mean the loss of the Sacraments to some poor wretch lying in his dismal hovel. [ See Ushaw Magazine, June, 1895.] To the townspeople such heroism conveyed the reason why Catholics reverenced the office of the priest ; for Catholics it knit fresh bonds between them and the clergy.

In the midst of these scenes of desolation the sad news arrived from Genoa that the great defender of the poor Irish, the brilliant advocate of Catholic claims, had given up his soul to God. The death of O”Connell added to the grief and suffering of the poor immigrants, whose confidence in his powers knew no bounds. It was announced in the ” Tablet “ that his body would pass through Liverpool on its way to mother earth, but the authorities, fearing an outbreak, induced his unintelligent son to alter the arrangements. Instead of coming to Liverpool from Southampton, the coffin passed through Chester, where it rested one night before the altar in the city of St. Werburgh, and on the 26th July, 1847, arrived in Birkenhead. The steamer ” Duchess of Kent ” lay in the Mersey, en route for Dublin. Its quarter-deck was covered with an immense black canopy, under which the coffin was placed, surrounded by lighted tapers, and covered with a pall still in the possession of the Benedictines at St. Mary’s. To relieve the poignant feelings of the Irish multitudes they were allowed in relays to board the steamer and kneel for a few moments before the remains of the ” Liberator.” The evening before, the body of the O’Conor Don, M.P., lay in similar state ere it passed down the swiftly flowing waters of the Mersey to the land from whence he sprang. By November the tide of immigration began to slacken, and the black cloud of death and disease became less heavy and sombre. As the months rolled on, every quarter of the town had suffered, and, excluding those who had succumbed, sixty thousand of the inhabitants had suffered from fever and forty thousand from diarrhoea or dysentery. [Dr. Duncan s Report, page 18.]

The year 1848 opened with a great improvement in the death-rate from ” Irish fever,” but scarlatina and influenza now began to play havoc with the juvenile population. The deaths from fever during 1848 had fallen to 989; scarlatina claimed 1,516, and other zymotic diseases accounted for 4,350. [Dr. Duncan s Report, page 18.] From January, 1848, to April, 1849, 1,786 fatal cases of scarlatina occurred with children under 15 years of age, and when, in 1849, the horrors of Asiatic cholera were superadded, out of 5,245 deaths 1,510 cases were those of the same tender years, not including the 1,059 carried off by dysentery. [Dr. Duncan s Report, page 18.] The importance of these figures from the point of view of Catholic Liverpool is that seven-eighths of the dead were Irish; [Dr. Duncan s Report, page 18.] famine at home being exchanged for death abroad.

There were then in Vauxhall Ward, to take only one part of the typical Irish quarters, 27 streets, 226 courts, and 153 cellars. In the street houses 6,888 persons found a shelter, and in the courts, exclusive of the cellars, 6,148; or, as the Rev. Dr. Cahill put it, they crowded the desolate garret, the putrid cellar, and the filthy lane. In normal days in this district and Scotland Ward the deaths were in the ratio of one to fourteen of the residents as compared with one to thirty-eight in Rodney and Abercromby wards. According to a census taken by a well-known Anglican clergyman, Canon Hume, who made a house-to-house visit, there were 3,128 children between the ages of three and a half and twelve without the slightest school accommodation, and if we include those up to fourteen years of age, at least one thousand more must be added to the number. ” Crime,” as the word was then used, had begun to increase. In 1845 there were 3,889 cases; in 1846, 4,740; in 1847, 6,510, in 1848, 7,714; and in 1849, 6,702. The cause we have already indicated. Mr. W. Rathbone, at a meeting to raise funds, declared that it was the Irish landlords and not the people who ought to have been forcibly immigrated. Mr. Rushton, in his report to the Home Secretary, dated April 21, 1849, gives his view of the increase in ” crime.”

” I saw from day to day the poor Irish population forced upon us in a state of wretchedness which cannot be described. Within twelve hours after they landed they would be found among one of three classes, paupers, vagrants, or thieves. Few became claimants for parochial relief, for in that case they would be discovered and might be sent back to Ireland. The truth is that gaols, such as the gaol of the borough of Liverpool, afford the wretched and unfortunate Irish better food, shelter, and raiment, and more cleanliness than, it is to be feared, many of them ever experienced elsewhere ; hence, it constantly happens that Irish vagrants who have offered them the choice of being sent back to Ireland or to gaol in a great many cases desire to go to prison.” This awful picture was confirmed by the Prison Commissioners in the same year, who speak of ” the intensity of the distress, and the vast immigration of Irish paupers who commit petty offences in order to be sent to prison. At the time of our visit to the gaol more than one-third of the males were of this description, and more than half of the females.” Here are two official statements as to the origin of ” Irish crime,” to be aggravated as the succeeding years rolled on by the same causes, poverty, overcrowding, casual employment, and the natural consequence of all three, excess in drink. Compare these figures with the annual report furnished to the justices by the Anglican Chaplain of the gaol.

In the year 1841 there were 201 prisoners committed to the Assizes for serious crime, 35 being Catholics; committed to the Sessions for less serious crimes 317, 66 being Catholics. The Courts of Summary Jurisdiction or Police Courts committed 1,541, the Catholics numbering 486. From a population numbering a third of the whole these figures show no sign of ” Catholic crime “ being in undue proportion; [See Mr. Edward Bretherton’s reply to Lord Sandon, who, in a speech in the House of Commons said Catholics were one-fourth. 1843.] decidedly the reverse, especially in the Assize and Sessions cases.

For the year 1842, 41 Catholics were sent from the Assizes out of a total of 185 ; from the Sessions 100 out of 472, and from the Police Courts 513 out of 1,536. During the year 1843, 1,410 prisoners were sent to Kirkdale Gaol; 78 Dissenters, 280 Catholics, and 1,036 Protestants. Crime began with the poverty of the victims of the great famine, and was due to causes over which they had little control.

Their children were the greatest sufferers, the inheritors of a sad past. The want of schools was the main cause, for, as Father Nugent wrote sixteen years later in his first report to the justices, “education is not an absolute preservative against crime, yet it must always be an incalculable advantage towards gaining an honest livelihood, and making a position in a town like Liverpool.” [Annual Police Report, October 26th, 1864.] The children’s story has yet to be told.

The Corporation now plunged headlong into the work of sanitary reform, and blundered badly. The solution of the whole question lay, according to their notion of things, in closing insanitary cellars. From 1847 to 1849 they ejected 25,015 persons who dwelt in cellars, a desirable course to pursue provided they offered better surroundings or knew that private enterprise would supply them. One result did accrue, which was to overcrowd still more the houses already too fully occupied. [See Dr. Duncan’s report. He appealed to his committee to proceed cautiously in the evictions.] Tenement houses have been Liverpool’s second greatest curse, the fruitful cause of intemperance amongst women and even worse evils. Local authorities had not then the powers obtained thirty years later, and on that score the Liverpool Town Council was not entirely blameworthy. It was, however, unsympathetic, short-sighted, indifferent.