The Tablet Page 17, 15th March 1879

REV. DR. O’BRYEN.—The Rev. Dr. Henry O’Bryen has left Rome for Nice for change of air after his recent serious indisposition.

The Tablet Page 17, 15th March 1879

REV. DR. O’BRYEN.—The Rev. Dr. Henry O’Bryen has left Rome for Nice for change of air after his recent serious indisposition.

TRANSCRIPTION OF THE MARRIAGE SETTLEMENT OF HENRY HEWITT O’BRIEN AND MARY ROCHE DATED 27th OCTOBER 1807, no.404481

To the Register appointed by Act of Parliament for Registring Deeds Wills & so forth

Memorial of an Indented Deed of Settlement bearing date the twenty seventh day October one thousand eight hundred and seven, and made between Henry Hewitt O Brien of Broomly in the County of Cork Esquire of the first part John Roche of Aghada in the County of Cork Esquire And Mary Roche Spinster only daughter of the said John Roche of the second part, and John Roche the younger of Aghada aforesaid Esquire and Stephen Laurence O Brien of the City of Cork Esquire Doctor of Physic of the third part and what was made previous to the Marriage of the said Henry Hewit O Brien with the said Mary Roche whereby the said John Roche did agree to give as a portion with his said Daughter Four thousand pounds Stock in the Irish five per Cent Funds, By which said Deed whereof this is a Memorial the said John Roche for the consideration therein mentioned Did grant Assigne Transfer and set over unto the said John Roche the younger and Stephen Laurence O Brien All that the said Four thousand pounds Stock in the Irish five per Cent Funds To hold the same unto the said John Roche the younger and Stephen Laurence O Brien and to the Survivor of them his Executors Admst & Assigns up [sic] Trust, to permit the said Henry Hewit O Brien and his Assigns during his life to take the Interest Money, dividends and produce thereof for his own uses and after his death, to permit the said Mary Roche (in case she shall happen to survive the said Henry Hewit O Brien) and her Assigns during her life to take the Interest Money, dividends or produce thereof for her own use, by way of Jointure from and after the death of the survivor of them the said Henry Hewit O Brien, and Mary Roche, as to the said Sum of four thousand pounds upon Trust for the Issue of such Marriage if any shall be, but in Case there shall be no Issue or in Case there should, and that all such shall dye before any of them shall be entitled to their respective shares of the said Sum, then as to the intire said Sum of four thousand pounds Stock in the Irish five per Cent Funds and all benefit to be had thereby, upon Trust, for the survivor of them the said Henry Hewit O Brien and Mary Roche his intended Wife, his, or her Heirs Exrs Admrs and Assigns and it is by sd Deed expressed that the sd John Roche the younger and Stephen Laurence O Brien shall when thereto required by the sd Henry Hewit O Brien invest the intire of the said Trusts Money, or any part thereof, in the purchase of Lands in Ireland which Lands when so purchased are to remain to the same uses and Trusts as are mentioned and expressed in every aspect as to the Trust Sum of four thousand thousand [sic] pound in the Irish five per Cent Funds To which Deed the said John Roche Henry Hewit O Brien & Mary Roche put their hands and Seals, Witness thereto and this Memorial are John Cotter of the City of Cork Merchant, and John Colburn of sd City Gent.

Note:

Jointure – sole estate limited to wife, to be employed by her after her husband’s death for her life.

From Burke’s Landed Gentry – 1833

Callaghan Of Cork

Callaghan Of Cork CALLAGHAN DANIEL esq of Lotabeg in the vicinity of Cork now, for the third time MP for that city. Mr Callaghan who was born 7th June 1786 succeeded his father in April 1824

Lineage

Daniel Callaghan esq. one of the most enterprising and successful merchants of Ireland b. in 1760, espoused in 1782 Miss Mary Barry of Donnalee and dying in April 1824 left by that lady who survives, six sons and three daughters viz:

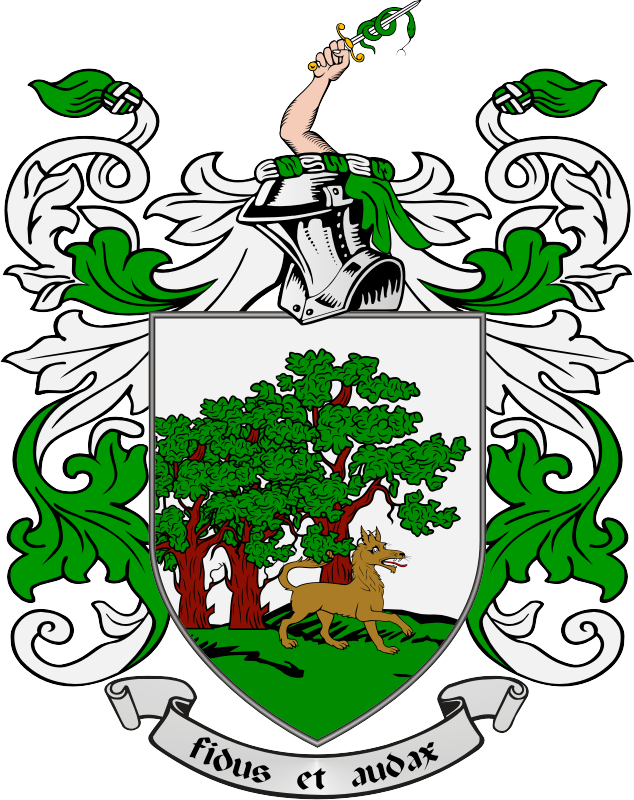

Arms – Az in base a mount vert on tb sinister a hurst of oak trees therefrom issaant a wolf passant ppr. Crest A naked arm holding a sword with a snake entwined. Motto Fidus et audax. Estates, In the county of Cork Seat Lotabeg

and from BLG 1847

Callaghan Of Cork

CALLAGHAN DANIEL esq of Lotabeg in the vicinity of Cork now, for the third time MP for that city. Mr Callaghan who was born 7th June 1786 succeeded his father in April 1824

Lineage

Daniel Callaghan esq. one of the most enterprising and successful merchants of Ireland b. in 1760, espoused in 1782 Miss Mary Barry of Donnalee and dying in April 1824 left by that lady who survives, six sons and three daughters viz:

I Catherine espoused James Roche esq of Aghada county Cork

II Anne

III Mary

Arms – Az in base a mount vert on tb sinister a hurst of oak trees therefrom issaant a wolf passant ppr Crest A naked arm holding a sword with a snake entwined Motto Fidus et audax Estates In the county of Cork Seat Lotabeg

Dorothy Bell was the daughter of Arthur Smith-Barry, Lord Barrymore. So she is a second cousin of Pauline Barry (nee Roche)’s granddaughters Nina, and Emily, who are in turn, Mgr Henry, Corinne, Basil, Alfred, Philip, Rex, and Ernest O’Bryen‘s third cousins. Dorothy’s father had owned Fota House, which was inherited by his brother James, and then his nephew Robert. Dorothy Bell bought the estate back from her cousin Robert in 1939, for £ 31,000. Quite how the family managed to hold onto their land, and money given Lord Barrymore’s behaviour to his tenants in the 1880’s is some mystery, as is the following description of life at Fota House in the 1940’s. Essentially, it wouldn’t have been much different at any time in past hundred and fifty years.

The following description of life at Fota House is largely taken from ‘Through the Green Baize Doors: Fota House, Memories of Patricia Butler’ , and various interpretations of it in the Irish Times, and Irish Independent about five years ago. The subtle distinctions between Irish and English staff, – Two weeks holiday for Irish staff, and a month for English staff, separate dining rooms, and an acceptance of the big house having hot and cold running water while there was none in the village, and the “Oh weren’t the gentry lovely” take on things appears to be a perfect example of false consciousness. Over to Patty Butler.

Back in the 1940s, when Dorothy Bell — mistress of the Big House at Fota — arrived home from a day’s hunting, she never did so quietly. She would, recalls former maid Patty Butler, rush through the front door, ringing the bell, and stride through the hall and up the stairs, calling the servants one after the other, “Mary!” “Patty!” “Peggy!”, discarding as she went her picnic basket, jacket, the skirt she wore over her jodhpurs for side-saddle riding, her whip and her hunting hat. As the staff, including the butler, rushed to pick up Dorothy’s belongings, her lady’s maid hurried to run a bath.

Patty was just 23 when she started work as the “in-between maid” at Fota House in 1947, after returning to Cork from England. On the advice of her cousin Peggy, who was working in Fota as the parlour maid, Patty applied for the job.

On the day of the interview, a somewhat awed Patty, who came from the nearby village of separate, was shown into the library by the butler, George Russell. “To me, the inside of Fota House on that day seemed like a palace,” she recalls. “I felt very small but also very excited in the midst of all this grandeur.” She was greeted by the mistress, who was sitting at a desk. The interview was brief. “Patty, have you come to join us?” inquired Dorothy. “The housekeeper will show you your duties. It won’t be all clean work, so you won’t be dressed up as you are now. Mrs Kevin will tell you what to wear.” And with that began a quarter of a century of dedicated service, as Patty became a member of staff in the efficiently run, though sometimes-eccentric, household a few miles outside Cobh. Over the years she was promoted to housemaid, lady’s maid and eventually cook.

Before Patty’s arrival, the family — The Honourable Mrs Dorothy Bell, her husband Major William Bertram Bell and their three daughters, Susan, Evelyn and Rosemary — had been looked after by an army of servants. According to the census return for 1911, 73 people were on site at Fota House on Sunday, April 2nd, 1911. None of them were the Smith-Barry family who had lived in Fota House for generations, as records show they were away on holiday at the time. In the 1930s, an estimated 50 men had worked on the grounds of Fota alone, but by the time Butler took up employment in the Big House in 1947, overall staffing levels had fallen to about 13.

“I began working in Fota House in 1947. I worked there for about 25 years. I was initially employed as an in-between maid but later I worked in almost every capacity, as a housemaid, cook and housekeeper. The cook, Mrs Jones, who came to Fota with Mrs Bell from England, left after 45 years so Peggy Butler, my cousin, and I managed the cooking for Dorothy, her husband, Major Bell, other members of the family and visitors.”

“Mrs Bell had a secretary too, Miss Honor Betson. She had an estate agent and clerical staff who lived in the courtyard. Mr Russell, the butler from Yorkshire in England, supervised the household until he died on January25th, 1966. He died in Fota House.”

“There was a lovely homely feeling there. It was a very pretty house and Mrs Bell was very into flowers, so it was always lovely and very pretty,” recalls Patty, now 87.

“There was a lovely homely feeling there. It was a very pretty house and Mrs Bell was very into flowers, so it was always lovely and very pretty,” recalls Patty, now 87.

She was given her own comfortable bedroom in the servants quarters. “I had everything I needed: a bed, a wardrobe, a dressing table with a mirror and an armchair near the fireplace. I remember also a beautiful washstand shaped like a heart with three legs. On top of that, there was a jug and basin with a matching soap dish. “There was also a towel rail with a white bath and hand towel. All the servants’ rooms were similar.”

“There was some distinction between the upper (mostly English and Protestant) servants, and the lower (mostly Irish and Catholic) servants. We dined in separate rooms, the upper servants in the housekeeper’s room and the lower servants in the still room. But we were all the best of friends. There was no rivalry or no animosity.”

“We also enjoyed food and board. The food was fabulous in Fota, of course, as fresh fruit and vegetables were produced there all the year round in the market garden and in the fruit garden and orchard. From the farm in Fota came milk, cheese, butter and cream. Rabbit and pigeon were eaten regularly in those days. The servants ate the same as the Anglo-Irish family, more or less.”

The anecdotes are legion — the way the servants occasionally ‘borrowed’ the Major’s Mercedes to go to Sunday Mass when their van didn’t work. How the housekeeper, a kindly soul with a strong Scottish accent, kept a cupboard in her bedroom especially for the pieces of china she broke while dusting Dorothy’s treasured ornaments. The times the servants were all driven to Cork Opera House by the chauffeur — the Bells had a great affection for the theatre and felt their staff should enjoy it too.

And then there was Dorothy’s eccentric habit of cutting the fruit cake in such a way that nobody could take a slice without her knowledge, and, of course, the parties that took place when the Bells were away, travelling the world.

Local lads from the village were invited up to the Big House by their sisters for a bath and a fry-up — there was no running water in many houses until the 1950s, or even the 1960s, says Patty. However, Fota had its own generator for electricity and water was always supplied from a nearby well. “We’d fry them up rashers and sausages and they’d have the bath and use the beautiful big, soft white towels and they’d think they were in heaven. The boys would love the bath — they were in their 20s and wanted to go into Cobh all poshed up!”

One day, however, Dorothy remarked that she had received an anonymous letter claiming that Patty and Peggy were having “parties” in the house while she was away. As Patty stood there, quaking, Dorothy laughed and told her relieved maid that she had thrown the letter in the fire.

Every morning, Mrs Kevin’s bell rang at 7am. Patty rose, dressed in a blue dress with a big white apron and white cap, and set to her housekeeping duties, which included cleaning the Major’s study and hoovering, dusting and polishing the Housekeeper’s Room before having breakfast at 8am. At 8.45am, Patty would bring her assigned guest — Fota nearly always had guests — morning tea on a tray with dainty green teapots with a gold rim and matching teacups. “I’d wake her in the morning with a breakfast tray and a biscuit, open the shutters, pull back the curtains and tidy the room. If there were any shoes that needed to be polished, I would take them down and they would be polished by a man who came in.”

The bed linen was beautiful. Each linen pillowcase had the Smith Barry crest in the corner and frills around the edges. After ironing, Patty remembers, each frill had to be carefully “goofed” or “goffered” by hand until it was perfectly fluted.

The gentry came down for breakfast — kippers, kedgeree, rashers, sausages and eggs or boiled eggs, served with toast and fresh fruit from the garden — each day at about 9am. “You always knew they were gone down because their bedroom doors would be open. So you’d go up and make the beds and tidy the room and wash out the bathroom — but you had to be back behind the green baize door by 11am.” In the evenings, she wore a black dress with a small apron and a smaller white cap with a black velvet ribbon. Male servants also wore black.

The gentry came down for breakfast — kippers, kedgeree, rashers, sausages and eggs or boiled eggs, served with toast and fresh fruit from the garden — each day at about 9am. “You always knew they were gone down because their bedroom doors would be open. So you’d go up and make the beds and tidy the room and wash out the bathroom — but you had to be back behind the green baize door by 11am.” In the evenings, she wore a black dress with a small apron and a smaller white cap with a black velvet ribbon. Male servants also wore black.

“There was always lots to do,” she recalls. After the morning household tasks came lunch. “I’d be helping in the pantry and at the lunch. There was a long walk from the kitchen to the dining room — it was three or four minutes, but there were no trollies, so everything was carried by hand.” Lunch — which could be anything from roast beef to pigeon pie, rabbit, fish soufflé or cold meat in aspic jelly with vegetables from the garden, water and a selection of wines — could last from 1pm to 2.30pm.

Tea was at 5pm in the Gallery in summer and in the library in winter. “Tea, for which there were cucumber and marmite sand-wiches, scones, tea and a cake, could last until 6.30pm,” she says.

Tea was at 5pm in the Gallery in summer and in the library in winter. “Tea, for which there were cucumber and marmite sand-wiches, scones, tea and a cake, could last until 6.30pm,” she says.

At 7pm, the gentry would go up to their bedrooms to change and have a bath before dinner — a lengthy four or five-course affair, which usually included game from Fota Estate. “Each dinner was served with suitable trimmings. Butter and cream were used in food preparations, so the flavours were always delicious,” she says. The kitchen had meat from the cattle and Fota’s home-produced milk, cheese and butter, as well as veg and fruit from the garden.

“There were always visitors, there was always somebody staying. They had the shooting season, the fishing season, the tennis season, the seaside in summer, the hunting — all the seasons brought different activities. You’d know by the season what was happening.”

Christmas was a particularly memorable time, she recalls. A single large Christmas tree was placed in the Front Hall, decorated with streamers, silver balls and other decorations, and on Christmas morning Dorothy gave each of the staff presents. “I remember I got a white apron,” recalls Patty, who says the mistress also distributed gifts to her tenants.

“On Christmas morning, the family went to the library to exchange presents. They loved gifts such as books and music records, ornaments or exquisite boxes of chocolates.” The chocolates, she says, often lasted for weeks, as the family usually ate only one at a time.

On Christmas Day, the servants had Christmas dinner in the middle of the day in the Servants’ Hall, while the family helped themselves to a cold lunch in the dining room. “This was the only day of the year that they waited upon themselves so that we could enjoy our Christmas dinner,” Patty recalls. That evening, the servants lined up in the Hall to watch the family, in full fancy-dress — these clothes were stored in a special chest in the attic — parade into the dining room.

“We had to bow to them as they passed by. I remember one year in particular when I could scarcely stop myself from laughing. Mrs Kevin, the housekeeper, carried a bell behind her back and as she bowed to each individual, the bell rang out!” After the fancy-dress parade, the family enjoyed a traditional Christmas dinner followed by plum pudding. They later drank to each other’s health from a silver ‘loving cup’, which was passed around. The men played billiards and the women talked and drank coffee in the library until late in the evening.

There were plenty of famous guests at Fota: Lord Dunraven of Adare, Co Limerick, Lord Powerscourt from Wicklow, the Duke and Duchess of Westminster and, according to the Visitors Book of Names, “eight international dendrologists with illegible signatures”.

The Bells enjoyed life, Patty recalls. “They had a lovely life; they were into everything. They went to the Dublin Horse Show and to the summer show in Cork. In his study, the Major had pictures of the bulls and cows with their first-prize rosettes. “They had a very privileged life and they enjoyed it,” she continues. There always seemed to be plenty of money. Mrs Bell had her own money, while the Major was, says Patty, “supposed to be a wizard on the stock exchange. They also had the farm and they owned a lot of houses and property in Cobh and Tipperary”.

In the evenings, Patty recalls, it was her job to go back upstairs, remove bedspreads, turn down beds and prepare hot-water bottles. “Some guests brought their own beautifully covered bottles, otherwise, stone jars were used. Most ladies brought their own pillows covered with satin pillowcases because they believed satin did not crease the face. “They had pink satin nightdress cases covered with lace and tied with ribbons.”

Fota House, Patty remembers, was a home from home. “It was a very happy place. Mrs Bell was excitable and eccentric. She was very athletic and quick. It was a very happy time, all of it. In every household little things will happen to ruffle your feathers but, overall, it was a fabulous place to work, and it was the people who made it.”

“There were lovely people at Fota,” she continues. “They were extraordinary. There were men who were extraordinary craftsmen — there was a blacksmith, for instance and a shepherd and a stone mason. They’d usually have a young apprentice that they would be training up.”

By the 1960s, however, most of the servants had left. “There was only me and Peggy running the house. Pat Shea was the last butler. Little by little, the staff dwindled away: the cook left, the ladies’ maid left.” When George Russell died in 1966 — he had been butler at Fota for 45 years and came with the Bells from England — it was the end of an era, she recalls. “Mr Russell told me he would love to write a book about Fota. He was going to call it, ‘What the Butler Saw’.”

The household slowly began to change. A series of nurses were employed to nurse Major Bell in his declining years until he died. Dorothy moved to the Gardener’s House, which was situated in the orchard at Fota, and lived there until she died a few years after her husband, in 1975.

The estate today comprises 47 hectares of land, including the parkland, gardens and arboretum. In December 2007, the Irish Heritage Trust took over responsibility for Fota House, Arboretum & Gardens.

‘Through the Green Baize Doors: Fota House, Memories of Patricia Butler’ — a revised edition of ‘Treasured Times’ transcribed and arranged by Eileen Cronin

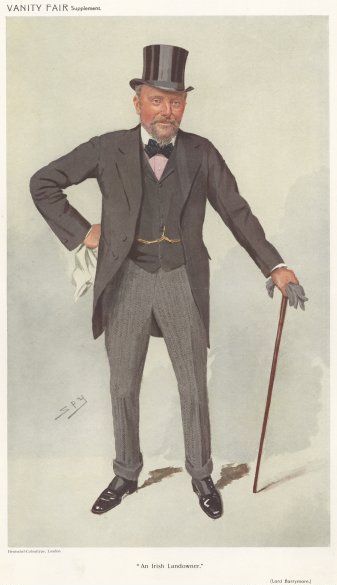

Arthur Hugh Smith-Barry, 1st Baron Barrymore, PC (17 January 1843 – 22 February 1925), was an Anglo-Irish Conservative politician.

He was the son of James Hugh Smith Barry, of Marbury, Cheshire, and Fota Island, County Cork, and his wife Eliza, daughter of Shallcross Jacson. His paternal grandfather John Smith Barry was the illegitimate son of James Hugh Smith Barry, son of the Hon. John Smith Barry, younger son of Lieutenant-General The 4th Earl of Barrymore (a title which had become extinct in 1823) He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford.

Smith-Barry entered Parliament as one of two representatives for County Cork in 1867, a seat he held until 1874. Smith-Barry remained out of the House of Commons for the next twelve years but returned in 1886 when he was elected for Huntingdon, and represented this constituency until 1900. He was also High Sheriff of County Cork in 1886 and was tasked by Arthur Balfour to organise landlord resistance to the tenant Plan of Campaign movement of the late 1880s. He was sworn of the Irish Privy Council in 1896. In 1902 the Barrymore title held by his ancestors was partially revived when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Barrymore, of Barrymore in the County of Cork.

Smith-Barry played two first-class cricket matches for the Marylebone Cricket Club, playing once in 1873 and once in 1875.

Lord Barrymore married firstly Lady Mary Frances, daughter of The 3rd Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, in 1868. After her death in 1884 he married secondly Elizabeth, daughter of U.S. General James Wadsworth and widow of Arthur Post, in 1889. There were children from both marriages, a son from the first, and a daughter from the second. Lord Barrymore died in London in February 1925, aged 82, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. His only son James had died as an infant in 1871 and consequently the barony became extinct on Barrymore’s death. The Irish family seat of Fota House was acquired by his daughter from his second marriage, the Hon. Dorothy Elizabeth Bell (1894–1975), wife of Major William Bertram Bell. Lady Barrymore died in May 1930.

On the death of Arthur Hugh Smith Barry in 1925, the estates, which were entailed, passed to his brother James Hugh Smith Barry and on his death it passed to James Hugh’s son Robert Raymond Smith Barry. In 1939 the estate of Fota Island and the ground rents of areas was acquired by Arthur Hugh’s daughter, The Hon. Mrs. Dorothy Bell for the sum of £31,000. On her death, in 1975, it was left to her daughter Mrs. Rosemary Villiers, and Fota House is now the property of The Irish Heritage Trust.

This is a almost unique wedding. The happy couple are married by the bridegroom’s father, who is a Catholic priest, and a hereditary papal duke. He is also the father of a legitimate son, and daughter. Mgr. George Stacpoole, was a Papal chamberlain at the same time as Mgr Henry O’Bryen.

The Rt. Reverend Mgr. George Marie Stanislas Koska de Stacpoole, 3rd Duc de Stacpoole, was born on 1 May 1829. He was the son of Richard Fitzgeorge de Stacpoole, 1st Duc de Stacpoole, and Elizabeth Tulloch. He was ordained in 1875 after the death of his wife, and was later made a Domestic Prelate by Pope Pius IX. He had married Maria Dunn, daughter of Thomas Dunn and Catherine Mary King, on 1 June 1859, He died on 16 March 1896 at age 66.

He was educated at Stonyhurst, and was decorated with the award of the Knight of the Supreme Order of Our Lord Jesus Christ (the highest Papal Order), he was also decorated with the award of the Grand Cross, Equestrian Order of Holy Sepulchre (at that time given by the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem under the protection and authority of the Pope).He became 3rd Marquis de Stacpoole, 3rd Duc de Stacpoole[both papal titles] , and 4th Comte de Stacpoole [a french title] in 1878. He lived at St. Wandrille, Rouen, France.

The marriage of the only son of Monsignor the Duc de Stacpoole, with Miss MacEvoy, only child of Edward MacEvoy, Esq., of Tobertynan, co. Meath, and Mount Hazel, co. Galway, and late M.P. for the former county, took place at the Oratory, Merrion-square Dublin,. on Saturday, 1st December, and was performed by Monsignor de Stacpoole, who afterwards addressed a touching and eloquent discourse to the bridegroom. The bride and bridegroom arrived shortly before eleven, attended by Mr. John Talbot as best man. The bride wore a dress of white satin, the entire front of which was of handsome Brussells lace, the gift of the Duc de Stacpoole, and was attended by six bridesmaids, Miss de Stacpoole (sister of the bridegroom), Lady Mary Nugent, Miss Ffrench and Miss Burke (cousins of the bride), and Miss Cicely de Stacpoole and Miss Dunn (cousins of the bridegroom), who were attired in dresses of cream-coloured satin and embroidery, trimmed with point d’Alencon lace, and cream-coloured bonnets with ostrich feathers. Each bridesmaid wore a gold bracelet with pearl horseshoe, and carried a bouquet of flowers, the gifts of the bridegroom. Master Arthur Burke, cousin of the bride, in page’s costume of black and white, acted as page. After the ceremony, Mr. and Mrs. MacEvoy entertained about ninety guests at dinner at their residence, 59, Merrion-square. Among the guests were : Monsignor de Stacpoole, the Right Rev. Dr. Donnelly (Auxiliary Bishop to the Cardinal), the Earl and Countess of Fingal, Dowager Lady Kilmaine, Lady Bellew, Sir Henry Burke, Hon. Mr. and Mrs. C. Nugent, Lady Mary Burke, Mr. and Mrs. Gradwell, Mr. H. Farnham Burke, Mrs. Athy, Mr. and Mrs. Morrogh, Lady Mary Plunkett, Mr. Granbey Burke, Mr. and Mrs. George Morris, Mr Martyn of Tullyra, Mr. and Mrs. O’Connor Morris, &c., &c. The presents numbered about 250. Besides these gifts from those who were present at the wedding, presents were received from the Dowager Marchioness of Londonderry, Lady Herbert of Lea, Sir Percival and Lady Radcliffe, Hon. Mr. and Mrs. Netterville, Hon. Mr. and Mrs. Bellew, Hon. Nora Gough, Hon. Arthur Browne, Mrs. Dunn, Countess of Westmeath, Lady Mary Nugent, Marquess of Sligo, Earl and Countess of Granard, Mr. and Mrs. George Lane Fox, Sir Henry Grattan Bellew, Sir Bernard Burke, Major Jarvis White, Miss Chichester, Mr. Coppinger, Mr. William Fitzgerald, Mr. Radcliffe, Mr. O’Connor, Mr. Ashworth P. Burke, Sir George and Lady O’Donnell, &c., &c. During the breakfast a telegram was received from Monsignor Mecchi, conveying a special blessing from his Holiness, who had previously deigned to bless the wedding ring, at the request of Cardinal Manning, who had been kind enough to take it to Rome. Shortly before four o’clock the newly married pair departed en route for the continent.

The above text was found on p.15, 8th December 1883 in “The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly.” Reproduced with kind permission of the Publisher. The Tablet can be found at http://www.thetablet.co.uk .

At least five members of the family were at this one. They’re starting to become part of the Catholic great and the good……………… Stuart Knill (no relation) was the first Catholic Lord Mayor of London since the Reformation, when he was elected six years later.

On Monday night the Annual Dinner of the Benevolent Society for Aged and Infirm Poor was held at the Albion Hotel, Aldersgate street.

Mr. Alderman Stuart Knill presided, and among those present were the Bishop of Southwark, the Bishop of Portsmouth, the Bishop of Emmaus, the Right Revv. Mgr. Canon Gilbert, V.G., and Mgr. Goddard ; the Very Revv. Canons Wenham, Moore, O’Halloran, McGrath, and Murnane, V.G., Father Aubry, and Dr Kelly, 0.S.A. ; M. l’Abbe Boyer and M. l’Abbe Toursel ; the Revv. J. Aukes, J. Bloomfield, J. J. Brenan, T. H. Burnett, D. Canty, T. Carey, G. Carter, P. Cavanagh, S. Chaurain, G. Cologan, J. Connelly, W. J. Connolly, C. A. Cox, G. S. Delany, E. English, M. Fanning, W. Fleming, T. Ford, F. A. Gasquet, 0.S.B., T. F. Gorman, W. Herbert, James Hussey, P. McKenna, T. F. Norris, C. O’Callaghan, D. O’Sullivan, E. Pennington, L. Pycke, T. Regan, F. Stanfield, L. Thomas, and E. J. Watson ; Judge Stonor, Mr. Alderman Gray, Mr. Deputy Young, K.S.G. ; Captain Kavanagh, Mr. J. Roper Parkington, Captain Shean, Dr. Ratton, and Messrs. W. A. Baker, J. Bans, Jun., W. Barrett, E. Belleroche, E. J. Bellord, John G. Bellord, M. Bowen, Augustin Boyle, Arthur Butler, George Butler, Jun., John Conway, E. Curties, F. H. Dallas, V. J. Eldred, R. M. Flood, E. J. Fooks, Garrett French, C. Gasquet, L. Gasquet, T. J. A. Grew, J. D. Hallett, W. B. Hallett, A. Hargrave, H. D. Harrod, J. Hasslacher, A. Hernu, J. J. Hicks, H. J. Hildreth, J. Hodgson, Alfred Hussey, James Hussey, John Hussey, Thomas Hussey, Thomas Hussey, Jun., William Hussey, J. B. Ingle, G. Pugh-Jones, W. Keane, Jun., J. M. Kelly, J. E. S. King, John Knill, Denis Lane, F. D. Lane, M. G. Lavers, C. Temple Layton, Dudley Leathley, F. Harwood Lescher, C. E. Lewis, Sidney Lickorish, W. H. Lyall, James PP. McAdam, James Mann, F. K. Metcalfe, J. Morris, W. J. O’Donnell, D. O’Leary, Thomas Osborn, Jun., Bernard Parker, Joseph J. Perry, Charles Petch, A. Pinto-Leite, Edmund Power, P. P. Pugin, Alfred Purssell, F. Purssell, E. Rimmel, E. W. Roberts, E. Rymer, Michael Santley, J. Scully, J. H. Sherwin, L. W. Stanton, C. F. Taylor, M. E. Toomey, W. Towsey, E. J. S. Turner, J. T. Tussaud, James Wallace, Thomas Welch, Stephen White, and J. J. Cooper-Wyld.

In proposing the health of the Pope, the Chairman said that his Holiness Pope Leo XIII., the two hundred and fifty-eighth occupant of the most ancient of thrones, was conspicuous by his watchfulness over Catholic and Christian interests and by his resistance to the powers of evil by which those interests were menaced. His wonderful Encyclical Letters on the great questions of the day were acknowledged by all to be perfect models of what should come forth from the true Shepherd of the sheep. Called on to arbitrate in international disputes ; called on to assert himself as the protector of his children in whatever part of the world they might be, he had by his justice and self-sacrifice won for himself the admiration of all—he had won for himself the hearts of his own children, and he had gained the veneration and respect of those who did not look upon him as their spiritual head. They were on the threshold of that year when the Holy Father would celebrate the jubilee of his priesthood ; and he asked them to fill their glasses and drink, as of old, to our “Bon Pere—his Holiness Pope Leo XIII”.

The toast having been received with great enthusiasm and drunk with musical honours, the health of the Queen and the members of the Royal Family was next given.

In proposing this, The Chairman said that civil power came from God, and was so closely allied to the spiritual that he had a great desire to unite the two toasts. It was a happy coincidence that while the Pope would celebrate the jubilee of his ordination, her Majesty would celebrate the jubilee of her coronation. They had for fifty years had the happiness of having a Sovereign who by her gentle sway, by her heartfelt sympathy with the joys and sorrows of our people, had gained the hearts of her subjects and justly deserved the title of Queen of our Hearts. And what was true of her Majesty was equally true of her Royal children. The Prince of Wales was ever amongst them taking part in every work which could promote the happiness and welfare of their fellows. He asked them to heartily drink the health of her Most Gracious Majesty and long life to the Prince and Princess of Wales.

The next toast was “The Health of the Cardinal Archbishop.”

In proposing this, the Chairman said that he regretted that their beloved Cardinal Archbishop was prevented from being present that night. They all knew the part which his Eminence took in any movement having for its object the alleviation of the sufferings of the poor. It was not for him to enter into details concerning his Eminence, but they all knew that he was ever ready to sacrifice everything for the good of his flock. By those outside the Church the Cardinal was looked upon as a true Englishman ; he had by his ability, by his gentleness, and by his readiness to take a part in every movement for the benefit of his fellows gained the respect and admiration of all with whom he had come in contact. They well knew the interest he took in their society, the love he had for the poor and aged. His constant visits to their annual gatherings ; his constant appeals to them not to forget that though other charities might be of more interest, they could never allow those old men and women whom their society regarded as their special objects of care, to want at all events any little comforts of life which they could supply, showed the interest he took in their society.

The Bishop of Emmaus, in responding to the toast, said that all through life the Cardinal Archbishop had devoted himself to the good of his fellows. The Prince of Wales, speaking of his Eminence, had said : “I consider Cardinal Manning a true patriot.” Those words certainly deserved their attention. However some of his countrymen might disagree with his Eminence on certain points, they all knew that he was a practical man ; they knew that he never spoke at random. What he did he did after mature consideration. It was indeed a subject for very great rejoicing that his Eminence had gained for himself the admiration and esteem of all classes of Englishmen. No one regretted the absence of the Cardinal that night more than he did, but his Eminence had asked him to make the appeal which he himself would have done had he been amongst them. He was sure that all were desirous of helping any movement once they were assured that it was deserving of their sympathy. He knew of no work more worthy of their charity than the providing for the poor and aged. The annual subscriptions for the year, he regretted to say, had fallen off £100. It was true that they had no increase in the number of their pensioners. Under the circumstances it would not be prudent to add to the number of their pensioners ; but nevertheless it was sad to see any falling off in the subscriptions.

Since the last report of their society no less than £5,484 had been paid to the poor pensioners in weekly instalments, and in otherwise helping them. He rejoiced to be able to say, especially in the presence of their chairman, that the merchants and bankers in the City of London had shown as much generosity as ever to their society, and that they contributed the magnificent sum of £500. He would not speak of Mr. Arthur Butler in his presence, but they knew well his exertions on behalf of the society. He was sure they would contribute generously that night. Their alms would be well bestowed. Many of the poor aged and infirm people, unable to earn their livelihood, had sought relief of the society, but the society could not go beyond its means, and so many applicants had to be refused its assistance. Many of these poor had seen happier and brighter days, and it was indeed hard to refuse them aid. But they could not do more than their means would allow. He could not help alluding to the death of one who had taken a deep interest in their society, and had laboured zealously on its behalf, the late Dr. Hewett. He felt certain that they would contribute generously to a work so well worthy of their sympathy, and thus show their interest in the oldest Catholic charity for the relief of distress in the great city where they dwelt.

The health of the Bishop of Portsmouth was next proposed by the Chairman, and that of the Bishop of Southwark by Judge Stonor, and the remaining toasts of the evening included the health of the Bishop of Emmaus, the clergy of Westminster and Southwark, Mr. Arthur Butler, the Stewards, and the Chairman.

The above text was found on page 36, 27th November 1886 in “The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly.” Reproduced with kind permission of the Publisher. The Tablet can be found at http://www.thetablet.co.uk .

Stuart Knill was the first Catholic Lord Mayor of London since the Reformation.

SIR STUART KNILL.

It is with deep regret that we announce the death of Alderman Sir Stuart Knill, which occurred early on Saturday morning at his residence, The Crosslets, The Grove, Blackheath, after an illness of about a month’s duration. We have dealt elsewhere with the lesson of his life, and we here avail ourselves of the source used by most of our contemporaries for the main facts of his career.

Sir Stuart was the son of Mr. John Knill, of Blackheath, and was born in 1824. He succeeded his father as head of the firm of Messrs. John Knill and Co., wharfingers and warehouse-keepers, of Fresh Wharf and Cox’s Quay, London Bridge. He took no part in municipal or official life until 1885, when, on the death of Sir Charles Whetham, he came forward in response to an influential requisition as a candidate for the Aldermanry of the ward of Bridge Within, in which his business was carried on. His opponent was Mr. (now Sir) John Voce Moore, the present Lord Mayor, and after a keen contest Mr. Knill was successful. He served the office of Sheriff of London in 1889, in the mayoralty of Sir Henry Isaacs, having as his colleague Mr. Walter H. Harris, C.M.G. In the ordinary course of civic rotation his turn for being elected Lord Mayor arrived in 1892.

Prior to the election an angry controversy was set up as to the desirability of electing as Chief Magistrate so fervent a Catholic as Mr. Alderman Knill, (who carried his religion to the extent of abstaining from attending official services at St. Paul’s Cathedral and other churches of the Establishment while holding high municipal position. Mr. Alderman Knill, however, in a letter to the then Lord Mayor (Sir David Evans) made it quite clear that to this conscientious attitude of his he intended scrupulously to adhere, whatever might be the consequences, but he promised, if elected, to appoint a clergyman of the Church of England as chaplain to the office of Lord Mayor—and in every other way to carry out the ancient duties and traditions of his position. At the election Mr. Alderman Knill was severely catechized on behalf of the Protestant citizens, but he never flinched from his decision. His name and that of Mr. Alderman (now Sir) George Faudel-Phillips—the one a Catholic, the other a liberal-minded Jew—were selected by the Livery for submission to the Court of Aldermen, who chose Mr. Alderman Knill.

His term of office was useful and dignified, and though he never attended church in state he escorted the Judges to the doors of St. Paul’s Cathedral and received them on their return from service. He paid a state visit to Dublin on New Year’s Day, 1893, for the inauguration of the Lord Mayor of that city, and was enthusiastically received by the Catholic populace. On the occasion of the marriage of the Duke and Duchess of York the Lord Mayor and the Sheriffs met the Royal couple at St. Paul’s, and escorted them through the City. The King and Queen of Denmark, who were in London for the wedding of their grandson, visited the Guildhall and were received by Lord Mayor Knill on the part of the Corporation. The Lord Mayor and Sheriffs also paid a state visit to Edinburgh in connection with the Congress of the British Institute of Public Health, and while there his lordship received the honorary degree of LL.D. of Edinburgh University.

A painful national event in Sir S. Knill’s mayoralty was the loss of her Majesty’s ship Victoria with over 400 lives, necessitating the raising of a Mansion House fund for the relief of the widows and orphans, to which £ 68,000 was subscribed. The Lord Mayor was appointed a Royal Commissioner of the Patriotic Fund for the administration of that and other kindred subscriptions. His hospitality was unbounded. Among other entertainments out of the usual sort he gave a dinner to M. Waddington, the French Ambassador, another to Field-Marshal Lord Roberts on his return from the Indian command, a third to the members of the Comedie Francaise, then visiting London, as well as a banquet in honour of music.

A notable banquet was that to Cardinal Vaughan and the Catholic Bishops of England. It was an exclusively Catholic gathering, but the Lord Mayor got into trouble over it with the Corporation and others for proposing as the first toast “The Holy Father, and the Queen.” No one doubted his loyalty, and his explanation that it was the usual Catholic formula—equivalent to the time-honoured toast “Church and Queen ” —was generally accepted. The almost concurrent announcement, through Mr. Gladstone, that the Queen had conferred on the Lord Mayor the honour of a baronetcy, in celebration of the marriage of the Duke and Duchess of York, showed at all events that no permanent, if any, umbrage was taken at the incident in high quarters. In 1897, on the death of Sir William Lawrence, Sir Stuart Knill accepted the sinecure aldermanry of the ward of Bridge Without, and the electors of his old ward—Bridge Within—paid him the compliment of choosing as his successor his son, Mr. John Knill. Father and son were thus aldermen of two adjoining wards.

Sir Stuart was a distinguished archeologist and antiquary, and a considerable traveller. He was last year president of the dilettanti society known as “The Sette of Odd Volumes.” He was a magistrate for Kent and London. At the first election of the London County Council he was a candidate for the Greenwich Division, but was unsuccessful. He was a leading member of the Plumbers’ Company, of which he had been Master, and took a principal part in the scheme for the examination of plumbers which has had such good results in sanitation. He was also on the Court of the Goldsmiths’ Company, and would have been Prime Warden (had he lived) next year, which would have been also the year of his golden wedding. As will have been gathered, he was a distinguished and respected member of the Catholic laity in this country, and he supported the charities of his faith with great liberality.

The Pope created him a Knight of St. Gregory, and the King of the Belgians an officer of the Order of St. Leopold. He was married nearly fifty years ago to Mary,daughter of Mr. Charles Rowland Parker, of Blackheath, and by her (she still survives him) had several children. His only surviving son and successor in the baronetcy is Mr. Alderman John Knill, who was born in 1856 and educated at Beaumont College. He is a magistrate for the City and County of London, and, like his father, a Catholic and a Conservative. He married, in 1882, Mary Edith, daughter of the late Mr. John Hardman Powell, of Blackheath, and grand-daughter of Augustus Welby Pugin, the distinguished architect and antiquary. They have one son.

Sir Stuart Knill’s death has occasioned great regret in the City, where he was universally popular and highly esteemed. The vacancy in the Ward of Bridge Without will be filled by one of the present aldermen, and in his ward, whichever it may be, an election of a new member of the Court will be necessary. In consequence of Sir Stuart’s death the annual banquet of the Worshipful Company of Plumbers, which had been fixed for the 23rd, was postponed. The Master and Wardens felt that to hold a social meeting under the shadow of such a loss would be alike repugnant to the sentiments of the members of the Livery and the guests who revered and admired Sir Stuart in his personal and public relations, especially those connected with the technical education and registration of plumbers, which Sir Stuart greatly aided in fostering in the interests of the health and comfort of the community.

CHURCH REFERENCES.

On Sunday at the different Masses in all the churches of the archdiocese of Westminster and the diocese of Southwark the customary prayers for the dead were offered up for the repose of the soul of Sir John Stuart Knill; and at St. Mary’s, Moorfields, which, during his year of office as Lord Mayor the deceased regularly attended from the Mansion House, St. Mary’s being the only Catholic place of worship in the city proper. Before the sermon at High Mass, which was celebrated by the Rev. Father Power, the Rev. Father M. Condon referred to the great loss which the Catholics and the Catholic charities of London had just sustained by the lamented death of Sir Stuart Knill, who was probably best known to his co-religionists throughout the British Empire as the second Catholic Lord Mayor of London since the Reformation. Exalted and coveted as that position was, it should not be forgotten that his entry upon such a distinguished civic office in a city like London, the largest and most Protestant city in the world, was, as it was only reasonable to suppose under the circumstances, beset with many difficulties and many embarrassments. But great as these difficulties were, the new Chief Magistrate of London successfully overcame them all ; and his manly fortitude and sterling independence of character, but more especially his uncompromising fidelity to the principles of his religion and unswerving obedience to her laws and mandates won for Sir Stuart Knill the respect and admiration of his fellow-citizens, Catholic and Protestant alike. And whilst expressing their deep sympathy with his sorrowing family in their sad bereavement, Father Condon said he could not help thinking that the best tribute they could pay his memory was the tribute of their sincere and earnest prayers to Almighty God for his eternal repose. May he rest in peace. The deceased baronet and alderman was a liberal supporter of the various charitable institutions connected with the Catholic Church in the metropolis, the preacher mentioning particularly his munificent contributions to the Providence-Row Night Refuge and the generous aid he always rendered its founder, the late Right Rev. Mgr. Gilbert, in the maintenance of that very useful charity. R.I.P.

LETTER FROM CARDINAL VAUGHAN.

His Eminence Cardinal Vaughan has addressed the following letter to the clergy of the diocese of Westminster : “There is special reason why I should commend the soul of Sir Stuart Knill to the prayers of the faithful. He stood forth in public life, a bright and conspicuous example to his fellow-countrymen of a fervent an consistent Catholic. Raised by the confidence and good will of the Corporation of the City of London to the pinnacle of civic honour, he never at any time sacrificed, or even compromised, perfect uprightness and loyalty to his religion in order to win worldly favour. It is as honourable to the character of the City of London as to himself to say that the simplicity and consistency of his Catholic conduct, far from alienating, won public admiration and esteem. Sir Stuart Knill as Lord Mayor of London has left us this lesson— that the English people appreciate thoroughness in religion and unswerving fidelity to principle, when not dissociated from kindliness and consideration for the feelings of others ; and that, in England, there is no reason why any man should abate his Catholicity in order to discharge efficiently the highest duties in public or civic life. ” The Times, in its obituary notice, records that Sir Stuart Knill carried his religion to the extent of abstaining from attending official services at St. Paul’s Cathedral, and other churches of the Establishment, while holding high municipal position; and it states that he got into trouble with the Corporation and others for proposing at a Catholic festivity in the Mansion House, as the first toast, “the Holy Father and the Queen.” But it generously and truly adds that no ones doubted his loyally: and his explanation that it was the usual Catholic formula, equivalent to the time-honoured toast “Church and Queen,” was generally accepted ; and the almost concurrent announcement that the Queen had conferred on the Lord Mayor the honour of a Baronetcy showed at all events that no permanent, if any, umbrage was taken at the incident in high quarters.

“While deploring the loss of one whose long life was marked by charity to the pour, generous support of Catholic works, and many conspicuous civic and public -virtues, such as the Church delights to honour, I beg that Masses and prayers be offered to the all-merciful God for the eternal repose of his soul, if it be still in need of our suffrages.

“I take this opportunity to recall to your minds, Rev. Fathers, if it, be necessary-to do so that, in accordance with the directions given in the 32nd Diocesan so, of Westminster, page 40, a Novena or a Triduo for the souls in Purgatory is to take place during the month of November in every public church. Do not fail in this great act of charity towards those who suffer.”

The Bishop of Southwark has also asked the prayers of the faithful in the following circular to his priests : “We beg the prayers of the faithful for Alderman Sir Stuart Knill, who passed from this life yesterday. The noble Catholic life that he always led, the zeal that he ever manifested for Catholic interests, and the special ties that attached him, to our Cathedral and our diocese, so often and in so many ways befriended by his charity, make it a grateful duty for us all to remember him in our prayers, and to beg our Lord to grant him everlasting peace, and to console those who are left to mourn him.”

The above text was found on p.27, 26th November 1898 in “The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly.” Reproduced with kind permission of the Publisher. The Tablet can be found at http://www.thetablet.co.uk .

This is one of a series of posts covering Pauline Roche’s marriage into the Barry family,All three of her daughter Edith’s sons served in the First War, both Will and Joe in the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, and Gerard in the Royal Fusiliers.

The following text was found in “The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly.” Reproduced with kind permission of the Publisher. The Tablet can be found at http://www.thetablet.co.uk .

The following names are of wounded officers :—Major Adrian CARTON DE WIART, D.S.O., 4th Dragoon Guards, attached Gloucester Regt. (Oratory) ; SecondLieut. Peter Paul MCARDLE, York and Lancs. Regt. (Stonyhurst) ; Lieut. Henry Aidan NEWTON, Northumberland Fus. ; Second-Lieut. Edward Thomas RYAN, R. Irish R. (Stonyhurst); Second-Lieut. William J. ROCHE, R. Irish R:; Captain William J. HENRY, M.B., R.A.M.C., attached 6th Wilts R.; Captain Henry Edward O’BRIEN, R.A.M.C.; Lieut. G. P. HAYES, R. Fus., attached Trench Mortar Battery (Beaumont) ;

The above text was found on page 20, 5th August 1916

THE MILITARY CROSS. • The award of the Military Cross is gazetted to the following officers : To Lieutenant (temporary Captain) Joseph Barry Hayes (Beaumont and Wimbledon), son of the late Major P. A. Hayes, R.A.M.C.—” For organizing a front line after an attack, under heavy fire and in difficult circumstances lasting for two days. He had lost both his subalterns in the attack.”

The above text was found on page 11, 7th October 1916

The following names, accorded special mention by Sir D. Haig, form a continuation of those published last week. The concluding portion will appear in our next issue :HAYES, Capt. (T. Major) William, E. Surrey R. (Beaumont.)

The above text was found on page 22, 26th May 1917

Captain William Hayes, D.S.O., Queen’s (R. West Surrey) Regt. and Staff Captain, died on October 20, at a stationary hospital abroad, of pneumonia following influenza.. He was the eldest of the three sons of the late Major Patrick Aloysius Hayes, R.A.M.C., and of Lady Babtie, and step-son of Lieut.-General Sir William Babtie, V.C. Born in 1891, he was educated at Beaumont and Sandhurst, and was gazetted to the Queen’s in 1911. With the 1st Battalion he accompanied the original Expeditionary Force to France, taking part in the Mons retreat and the battles of the Marne and the Aisne, in the latter of which he was very severely wounded. He returned to the Front in 1915, joining the 2nd Battalion of his regiment, but was soon afterwards invalided as a result of shell concussion. In 1916 he rejoined the 2nd Battalion in time to take part in the battle of the Somme. He was appointed second in command, with the temporary rank of major, and for his services in that capacity while in temporary command of his battalion was mentioned in dispatches, and awarded the D.S.O. in 1917. Later in that year he proceeded to another front, and in 1918 he was appointed Staff Captain on the lines of communication. He had just returned from leave in England when attacked by influenza. One who knew him writes :—” A keen soldier, whose heart and soul was in the honour and credit of the Queen’s, he was a man of character and of great personal charm, and his memory will live long in the hearts and minds of his regiment and of his multitude of friends in and out of the Army.”

The above text was found on page 18, 2nd November 1918

Pauline Roche (1835 -1894) has been part of the story for a while. But I’m becoming increasingly sure that she helps place a lot of things into context. This is one of a series of posts covering her marriage into the Barry family, and her daughter’s marriage into the related Smith-Barrys, and a look at where they all fit into both Irish, and British society.

Pauline & William Henry Barry had seven children, five of whom were unmarried, only two of the girls marry. Their children were:

Edith marries twice, and has three sons with her first husband; William, and Joseph b. 1891 who are twins, and then Gerard b. 1893, a year later,, and a daughter, Janet b. 1905, with her second.

Mary married Cecil Smith Barry, and had two daughters Cecily Nina b 1896, and Edith b 1907

So the grandchildren are:

Edith married Patrick Aloysius Hayes (1847-1900) who was born in Dingle, Co Kerry in 1847, and was a surgeon-major H. M. Army Medical Department, and they had three sons; William Hayes 1891 – 1918, J B (Joseph Barry )Haynes 1891 – 1927, and Gerard Patrick Hayes. Will and Joe appear to be twins, according to the 1901 census, both aged 9, Gerry is a year younger at 8, so probably born in 1892. Patrick Hayes Senior died in Wimbledon on the 20th March 1900. Edith then married Lieutenant General William Babtie V.C (1859 -1920), as a widow in 1903, and had a daughter Janet born in 1905.

Edith died on 25th June 1936 at 18 St Patrick’s Place, Cork and her address was given as The Hermitage, Rushbrooke, Cork; probate was given to Gerard Patrick Hayes, who described himself as an advertising salesman.

Mary and Cecil Smith-Barry had two daughters, Cecily Nina b 1896, and Edith b 1907. Cecily died in Bournemouth in the winter of 1954, “aged 56” actually 58. By that point she was firmly calling herself Nina Cecily. She was entered on the General Register of Nurses on Feb 16 1923, and still on the register in 1940, where her address was given as 9 Walkers Row, Fermoy, co. Cork. 1937 her address was Ruddiford, Wimborne Road, Red Hill, Bournemouth. She got her nursing certificate between 1917-1920 at St George’s in London. By 1943 she was at 3 Bodorgan Road, Bournemouth. There is very little trace of Edith Smith-Barry to date.

All three of Edith’s sons served in the First War, both Will and Joe in the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, and Gerard in the Royal Fusiliers.

Will was awarded a D.S.O. (Distinguished Service Order), and Joe a M.C. (Military Cross). The D.S.O. is awarded for an act of meritorious or distinguished service in wartime and usually when under fire or in the presence of the enemy. The Military Cross is a decoration for gallantry during active operations in the presence of the enemy. The decorations rank two, and three, respectively, in the order of precedence behind the Victoria Cross, which, incidentally, was awarded to their step-father Lieut.-General Sir William Babtie during the Boer War.

William Hayes died of flu on the 20th October, 1918, in Italy, and is buried at Staglieno Cemetery, Genoa. He had served throughout the First War, having been part of the original Expeditionary Force in 1914; out of the 1,000 men of 1st Battalion The Queen’s Royal Regiment who landed in France in 1914, only 17 were alive at the Armistice. So Will almost made it.

Gerard was wounded in 1916, when he was also mentioned in dispatches by Sir Douglas Haig, and Joe was awarded the Military Cross the same year. Will was mentioned in dispatches, and awarded the D.S.O. in 1917.

Joe survived the war, but died on December the 19th, 1927, aged 35. He had married in the winter of 1920, and his widow Gwen [nee Harold] survived him, and died almost fifty years later in 1976. Their address was given as the Very House, Worplesdon, Surrey, when Gerard Patrick was granted probate. Joe left £ 226. 13s. 11d., a present day equivalent of about £ 66,000.

Pauline Barry died in the autumn of 1894, aged 56. The registration district was Midletown, in co. Cork, so we can safely assume that she died at home in Ballyadam. All three of her grandsons had been born before she died, but none of her granddaughters.

Patrick Hayes died at Wimbledon on the 20th March 1900, presumably at 132 Worple Road Wimbledon where the boys were living at the time of the census in 1901. The house itself appears to be a relatively small two storey late Victorian semi-detached house. The greatest curiosity is that, at the time of the 1901 census, all three boys were living there without their mother, and only three servants looking after them. Elizabeth O’Shea aged 30, described as a nurse domestic on the census, but presumably their nanny; and Mary Phillips, a 21 year-old house maid, and Violet Gatling, also 21, who was the cook. The census was taken ten days before Will, and Joe’s tenth birthday on the 11th of April.

The censuses in 1901 in both Ireland, and England were taken on the same day 31st March, though the forms in Midleton in Ireland were not filled in until the 12th April 1901. They show that Edith Hayes was in Ireland staying with the Coppinger family at Midleton Lodge, rather than with her brother and sisters at Ballyadam House, nearby. There could be any number of reasons for this, Pauline, and Rose Barry are both living at Ballyadam with only one servant, in a sixteen room house outside of town, whereas the Coppingers are in the middle of Midleton in a rather larger house, with four daughters aged between eleven and twenty-one, a governess, and seven servants. Quite simply, it may well be that life at Midleton Lodge was a bit livelier, and as the widowed mother of three youngish sons Edith was looking for a rest, and some adult company. In all likelyhood, the Coppingers were also likely to be cousins of some sort.

Both families, the Barrys, and the Coppingers were living in considerable comfort, compared to the majority of the population of Ireland at the time. The Coppinger house appeared to have 22 rooms, and 20 outbuildings including 6 stables, a coach house, harness room, three cow houses, a calf house, dairy, piggery, fowl house, boiling house, barn, and a workshop, shed, and store. The house had “16 windows at the front” , in fact from the look of it, five windows at the front in a good solid double fronted Georgian house that is now the local council offices. Just to give some idea of how mobile all the families were Thomas Stephen Coppinger says in the 1901 census that he was a 57 year old merchant, born in Lucca, Italy in 1842.

Ballyadam, by contrast, was marginally smaller with 16 rooms, and 9 stables, a coach house, a harness room, 2 cow houses, a calf house, 2 piggeries, a fowl house, boiling house, barn, potato house, and 2 sheds. The Barrys were also listed as the owners of two 2-room cottages, each with 2 outbuildings next door to Ballyadam House.

The family living in the smallest house, though still more than comfortably, were Cecil, and Mary Smith-Barry. In 1901 they were in Castlemartyr, co. Cork, in the second largest house in the village, with 10 rooms, “eight windows at the front” , two stables, and a coach house. It was a mixed marriage, with Cecil a member of the Church of Ireland, and Mary and the children Roman Catholic. They only had one servant with them though, twenty-three year old Julia Casey.

At the time, 1901, Worple Road was just round the corner from the All England Tennis and Croquet Club, until it moved to Church Road in 1922. The site became the sports ground for Wimbledon High School for Girls.

By 1911, Will had been gazetted into the Army, Gerry was at Beaumont College, in Windsor, and Joe was an “army student” boarding at Edge Hill Catholic College in Wimbledon. Edge Hill became Wimbledon College, and it was a third of a mile, or about five minutes walk from 132 Worple Road. Amongst Joe’s fellow students were Charles Joseph Weld, Thomas Joseph Weld, and Cecil Chichester-Constable, whose aunt Esther had married Stephen Grehan Junior in 1883, and was the mother of Major Stevie Grehan, (1896 -1972) whose memoirs of the First War are held, and documented in the Grehan papers at University College, Cork.

So, slightly curiously, both Joe Hayes, and Cecil Chichester-Constable were both related to the O’Bryen’s at Ernest O’Bryen’s generation. Joe, Will, and Gerry’s mother was his second cousin, and Cecil’s uncle, Stephen Grehan Junior, was also his second cousin. It’s all a very small world.

It is not entirely clear as to where all the Hayes boys went to school. Both Will and Gerry went to Beaumont, in Windsor, with Will going on to Sandhurst, before receiving his commission in 1911. Joe was just short of twenty years old when he was described as an “army student” at Edge Hill, so old to still be at school. He may well have been at Beaumont as well. It would be slightly odd to send two out of three boys to one school, and one to another.

Beaumont was certainly grand, being where it was on the edge of Windsor Great Park, it rapidly developed a claim to being the “Catholic Eton”, a tag at the school was “Beaumont is what Eton was: a school for the sons of Catholic gentlemen”, though similar claims have been made for Stonyhurst , Ampleforth, and the Oratory. Beaumont was one of three public schools maintained by the English Province of the Jesuits, the others being Stonyhurst, and St Aloysius’ College, Glasgow. To be fair to all of them, Stonyhurst has much the greatest claim, having been founded in 1593 at St Omer, in France to educate the sons of Catholics, who couldn’t get a Catholic education in Elizabethan England. None of the other three were founded until the C19th.

The family were still all very close, and in the 1911 census all the unmarried Barry siblings were at Ballyadam House, along with Edith’s eight year old daughter, Janet Babtie, who was the youngest of Pauline and William’s grandchildren. They had a couple of servant girls, and amusingly, Pauline claimed to be two years younger than she was ten years before, and Rose was a year younger.

Meanwhile Mary Smith-Barry had moved to a smaller house about ten miles away at Ballynoe, on the outskirts of Cobh. She is forty-five years old, and has been a widow for three years. The house is rented from her late husband’s cousin Lord Barrymore, who seems to own most of the village. Mary seems to be living quietly in the village with her daughters (Cecily) Nina who is now fifteen, and four year old Edith, and a nineteen year old servant girl.

To put things in perspective, when Cecil died in 1908, he left just over £ 5,000 [ the best current-day equivalent is £ 3.2m]. In the same year, The Old Age Pensions Act 1908 introduced a non-contributory pension for ‘eligible’ people aged 70 and over. The pension was 5 shillings a week, about half a labourer’s weekly wage, or £ 13 p.a. Cecil’s £ 5000 was the equivalent of three hundred and eighty four years of old age pension, so Mary, and the children, were hardly paupers.