CHAPTER XXVI. This chapter is a mixture of rather worthy campaigning to open the museums for the moral improvement of working men, and the suppression of ” vice and immorality ” – almost always a good thing, and is counterposed with the fallout of the Arrow affair in Canton [Guangzhou] which was the start of the Second Opium War. So while Josh has political and business sympathies for Sir John Bowring, he may well also have some family loyalty. Sir John is the great-uncle of Adeline’s nephew Hugh Mulleneux’s wife Fanny. Either way, the war culminated in the destruction and wholesale looting of the Summer Palace in Beijing by British and French troops in 1860 and the legalization of the opium trade.

After the death of Joseph Hume [1855], Sir Joshua sought to carry out his work left unfinished. Next to the question of enlarging the suffrage, that of opening the museums to the working classes had of late years most occupied Mr. Hume’s attention. In 1846, he had submitted his first motion to that effect to Parliament, and in the last session he attended had renewed the effort. Sir Joshua had promised to continue it, and he kept his word. At this period some working-men formed themselves into a committee, for the purpose of keeping alive the interest in the question among their class. Round this nucleus numbers gathered, composed chiefly of men connected with the more artistic trades, of pianoforte makers, goldsmiths, jewellers, and carvers — artisans, who felt the importance, for their own instruction, of becoming familiar with artistic creations, and who were conscious of the advantages derived from such influences. The committee gradually developed into an association sufficiently important to style itself the ” Sunday League,” of which Mr. Hume became the president, and Mr. Morrell the secretary, and immediately proceeded to start a newspaper to disseminate its opinions throughout the country.

In 1854, the House of Commons’ Committee on Public-houses came to a resolution that, as a means of combating drunkenness, ” it was expedient that places of public recreation and instruction be open to the public on Sunday afternoons after the hours of two o’clock P.M. ”

The League considered this an opportune moment for presenting a petition to Parliament for ” the opening of the British Museum, the National Gallery, and Marlborough House, on Sunday. “ Sir Joshua Walmsley undertook to present the goldsmiths’ petition. Mr. Hume had promised to bring the question before the House of Commons during the course of the session. We have seen however, that he could find no day for its discussion, and in the February of the following year[1855] he died.

“ Several deputations waited on me soon after, “ says Sir Joshua, ” asking me to assume the presidency of the League, and to fight its battle in Parliament. To this invitation I replied, that my promise to Mr. Hume, and my own desire to continue a work that enlisted my heartiest sympathy, would lead me to accept the proffered post; but I knew that my conduct in the frame-rent question had made me many enemies in Leicester. At the next election I foresaw that my seat would be in jeopardy, and my parliamentary career might thus shortly be closed. The working-men persisting in their invitation, I acceded to it, and on the 28th March, 1855, I brought the question before the House. ”

When the House divided, out of two hundred and thirty-five present, forty-eight recorded their vote in favour of Sir Joshua’s motion.

” The men who so warmly stood up for the sanctity of the Sabbath forgot, in their zeal, that they demanded its rigid observance from the working classes alone. They denounced the profanity of a proposal, that would enable the poor man to look at pictures and other works of art on the Sabbath after morning service. They saw no profanity in their own privileged stroll among the curiosities of the Zoological or Botanical Gardens, or in the enjoyment of their West-End clubs. On the very Sunday following the debate on my resolution, I met in the Zoological Gardens, accompanied by his wife and two children, an ardent opponent of the measure. ‘ You here on a Sunday among the wild beasts ! ‘ I exclaimed stopping short and looking him full in the face as if astonished at the rencontre. He was much discomfited, but at once fell back on the reassuring logic of the difference of classes. ‘ Oh ’ he answered, ‘ it is a very different matter my taking a quiet stroll here with my family, and letting crowds of workmen rush off to the museums.’ “

” I could not admit the difference in principle, and as regards circumstances, the difference implied an argument in favour of the workman. In advocating the objects of the Sunday League, I was simply endeavouring to extend to the poor some of the civilising agencies that so abound in the daily life of the rich ”

While working with this aim. Sir Joshua found himself the centre of a very whirlwind of indignation.

” I was privately and publicly apostrophised, ” he says, “ as an infidel. The post daily brought me letters from clergymen addressing me as an atheist, ‘ an agent of Satan.’ From the pulpit, the same epithets were applied to me and the other supporters of the Sunday League. In Liverpool, on one Sunday, a hundred sermons were preached against us. In every town, in every parish, from every church and dissenting sect, a protest was raised against any attempt to do away with the holiness of Sunday; and were it really kept and observed in a holy manner, I should be the last to desire a change. “

In thickly-populated cities and in the drowsiest rural districts, the work of petitioning began. From the most revered pillar of the local church to the youngest Sunday-school scholar, all the members of the various congregations appended their signatures to the earnest prayer to Parliament not to open the doors of museums or the Crystal Palace to the people on the Lord’s Day.

Public meetings, in towns and villages, passed resolutions and expressed sentiments that would not have been out of keeping with the pharisaical spirit dominant in Jerusalem nineteen centuries ago. A society formed for the due observance of the Sabbath threatened with public exposure those who voted for Sir Joshua Walmsley’s motion. A Sabbatical frenzy seized the country. Amid all this tumult, it was difficult to hear the counter protests of thousands of hard-working artisans, who knew well that, among their class, Sunday was not a day of sanctity, such as all this commotion against its desecration implied; or to notice the calm verdict given by some of the highest intellects in England in favour of the objects of the Sunday League.

It required courage to face the storm that was raging, but Sir Joshua was not the man to be driven from any path he had entered after mature deliberation. The National Sunday League announced during the recess that the measure would again be brought before Parliament by its president in the ensuing session. On the evening of the 21st February, 1856, the lobby of the House of Commons was crowded The Speaker’s and Strangers’ Galleries were thronged, and conspicuous by their numbers were the clergy present. There was a perceptible stir of excitement through the assembly, deepening during the hour and a half employed in presenting petitions against the resolution that was to be the principal feature of the night’s debate. It was the evening for the discussion of Sir Joshua Walmsley’s motion for the opening of the museums on Sunday.

On this occasion his speech was more exhaustive than that delivered on the same subject the preceding year. He entered more fully into the bearings of the Sabbatarian movement, meeting the objections that had been so loudly urged against the objects of the Sunday League. Carefully abstaining, however, from any expression that might hurt sensitive, anxious souls, easily alarmed at what seems to them a lowering of that standard of faith necessary to salvation, he was nevertheless ” determined,” he said, ” not to shrink from any discussion calculated to elicit the truth, but truth applicable to all classes, and not an ideal to which our workers are sacrificed. Nor will I yield to any in an earnest desire to preserve the Sunday as free from labour as is consistent with the necessities of the people — a day of rest, devotion, and innocent enjoyment. I believe the measure now proposed is worthy the acceptance of the House, and calculated to elevate the moral and religious character of the people.”

” I am morally certain, “ he proceeded, after giving a summary of the petition signed by upwards of ten thousand workmen in favour of the opening of the museums, ” that were these institutions opened on the afternoon of Sunday, thousands, if not tens of thousands of persons, who now seldom leave their crowded courts and alleys on that day save to resort to the public- house, would be found with their wives and families visiting these pleasant centres of instruction. These people would return to their homes wiser and better men from the contemplation of the beautiful, and for their momentary contact with the finest products of the most gifted of our race. ”

After quoting eminent authorities, past and present, in favour of a brighter conception of the Sabbath, he laid his finger on the real evil the measure was chiefly directed against — drunkenness, that passion that saps and mines all force of character, wrecks virtue, and brings misery into the homes of our lower classes. This passion finds an accomplice in the tedium and stagnation of Sunday which well-nigh excuses and explains it.

Referring to the letter of a man of much practical experience, he showed that ” vice and immorality are relatively more prevalent in London than in the great Continental capitals ; and, especially, the relative proportion of immorality which prevails on the Sunday, compared with any other day of the week, is far larger in London than in the Continental capitals. In Edinburgh and Glasgow, where what might be called the judicial observance of the Sunday is stricter than in London, the vice and criminality prevalent on that day are also relatively greater than in London. ”

” This, “ reiterated Sir Joshua in conclusion, ” is an educational measure in its most comprehensive sense, and one that ought not to provoke religious controversy. As an educational measure, it would humanise and improve that class of the community, which millions spent in church establishments have failed to reach. ”

The discussion that followed was as intolerant in spirit, and as wide of the mark in its objections to the measure, as that of the preceding year. The comfortless homes of the poor; the fact that the large majority of working-men in crowded cities never enter a place of worship, but spend the Sabbath in gin-shops, for lack of a better place of entertainment to resort to; these realities were ignored by those who so loudly denounced the measure. Members of Parliament spoke as though the present observance of Sunday constituted godliness itself. It seemed as if to them Sunday was made holy by the mere fact of the doors of the museum being closed.

Lord Stanley again defended the motives of the Sunday League and its promoters. The faithful few of the year before spoke in favour of the resolution. When the House divided, it was found that the same forty-eight, out of the four hundred and twenty-four members present, had voted for Sir Joshua Walmsley’s motion. The Sabbatarian party received the announcement of their victory with ringing cheers.

In February, 1857, Sir Joshua moved “ for a Select Committee to consider and report upon the most practical means for lessening the existing inequalities in our representative system, and for extending to the unenfranchised that share of political power to which they may be justly entitled. ” The motion, however, found no favour with the House; after the fatigue and excitement of the Russian War, there was little zeal left for measures of home reform.

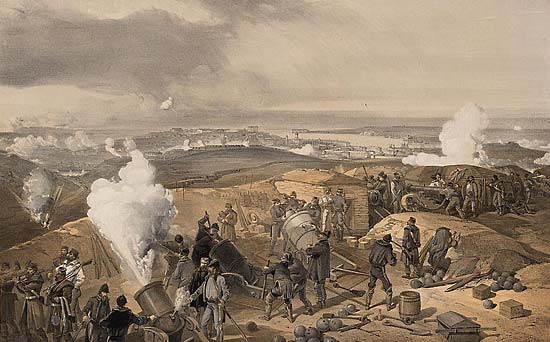

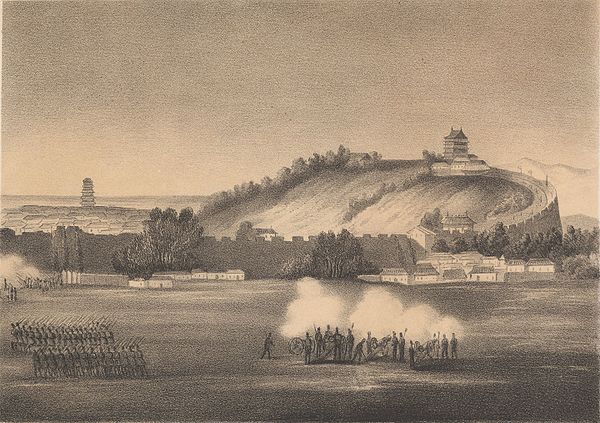

Sir Joshua brought forward this motion on the eve of the momentous debates in both Houses on the proceedings of Sir John Bowring in China, in the affair of the Arrow. Shortly before Christmas had come tidings by the Chinese mail, startling to ministers and the country, that for six weeks England had been at war with China. An insult had been offered to the British flag. In October, Chinese officials had boarded a Chinese vessel flying English colours, on a charge of having been concerned in an act of piracy, and carried off twelve of the fourteen that composed her crew. Swift and terrible retribution followed this act. The prisoners, indeed, had been given up, on the demand of Sir John Bowring, but Governor Yeh refused to make a public apology. Permission to foreigners to enter Canton, a condition insisted on by the English ambassador, had also been withheld. Then had followed the storming of the city of Hong Kong [ Hugh gets his cities wrong, and actually means Canton] and the shelling of Governor Yeh’s house.

On the 25th of February the debates on the Canton question began. Lord Derby brought the question before the Upper House. In a speech of fiery eloquence, he condemned the conduct of Sir John Bowring as hasty and cruel ” The Hotspur of debate “ failed on this occasion to carry with him the House of Lords. By a majority of thirty-six, the Peers justified the English ambassador’s action.

On the 27th, in the House of Commons, Mr. Cobden, true to the single-mindedness with which he ever pursued the great purpose of his life, set aside the claims of twenty years’ friendship, and moved “ that the papers which have been laid upon the table fail to establish satisfactory grounds for the violent measures resorted to at Canton, in the late affair of the Arrow. “ From the 27th of February to the 3rd of March the debates lasted Lord Palmerston stood by his appointed agent, and the ministerialists to a man supported him. Party spirit doubtless inspired some of the speeches delivered during that week’s discussion, but on reading the reports of it, the impression left on the mind is that the verdict given was deliberately and honestly arrived at. It recorded that, by a majority of sixteen, the representatives of the English people did not sanction the proceedings of their official in the Canton waters. Lord Palmerston, interpreting this decision to be a vote of censure on his Government, announced, a couple of days after, that he had advised the Queen to dissolve Parliament, and to appeal to the nation. It was a question on which there might well be a difference of opinion, and it was for the country to determine whether it would or not endorse that adopted by its representative ; accordingly, throughout the country there began the hubbub and preparation of a general election.

Sir Joshua says : ” I voted against Cobden’s motion. Personally I had a great regard for Sir John Bowring ; and I believed it was next to impossible to judge from a distance the fitting agencies to be brought to bear upon a people, whose code of political honour is so materially different from that of Western nations. I shared also Lord Palmerston’s opinion that government is bound to stand by the acts of a public servant, occupying a post of vast responsibility in a distant country, unless the case be clear against him. The Brutus-like severity with which Cobden denounced his old friend, impelled by a sense of public duty, made a deep impression on me .”

We have incidentally alluded to the correspondence between Sir Joshua Walmsley and Sir John Bowring; we think it may prove interesting to the reader here to append some extracts from the Governor of Hong Kong’s letters during this crisis in his life.

The first referring to this time is dated 11th April, 1857:

” My dear Sir Joshua,

“I hear from Edgar he has had some correspondence with you about Chinese affairs, and the course taken by The Daily News. It is the second occasion on which great injustice has been done me : firsts in the Shanghai duty question which is the chapter in my life’s history of which I shall feel proudest, and in which I sought to fight the battle of honesty and probity; second, the Canton affair, in which Weir has been so much led astray by . (there is a blank marked in the manuscript)

The newspaper here. The Chinese Mail, though much in the habit of abusing me, has on this occasion expressed a honest regret at the course taken by its proprietor. I would add that, though the merchants of Canton have been such sufferers, there is not one who has uttered a word of complaint against my proceedings, and they have been concurred in by the representatives of all the foreign powers, who are generally too well disposed to animadvert upon our proceedings. If my hands had not been tied by Lord Malmesbury, I would have settled the question peaceably years ago. It is a most erroneous and mischievous policy to allow Oriental nations to violate treaties, as it invariably encourages a continuity of acts that must end in collision. No man has ever done so much as I by pacific influences. Look at the Siamese Treaty, which has led in the first year to the lucrative employment of two hundred foreign ships, while the average preceding the treaty was only twelve. I have been knocking at every door in China with olive-branches in my hand, and have succeeded everywhere but at Canton ; and there I have never found anything but an obstinate determination to keep me at a distance, to disregard treaties, to show disrespect to our flag, to protect all who did us an injury ; in a word, to make the most solemn engagements a dead letter. I am persuaded justice will ultimately be done me, and I in the meantime must bear universal opprobrium, in addition to all the perils and responsibilities of my difficult position.

I have never met with a more humane man than the admiral, who has also been so much abused.

” Ever, my dear Sir Joshua, yours faithfully,

“John Bowring. ”

In the course of a letter, dated July, 1857, he writes :

” As regards China, I only wish they would have allowed me and the other ministers to have accomplished our work, and we would have obtained absolute indemnity for the past and a proud treaty for the future. But they have worked out a course of policy for themselves, and I believe Lord Elgin already feels he is engaged in the most serious difficulties. I shall aid him to the best of my power. It is natural enough that cabinets should suppose they know a great deal more about matters than those who receive their instructions from them ; but I presume we, who have lived so long in China, are, or ought to be, better acquainted with what can and what ought to be done than those who, ten thousand miles away, and whose opinions are the result of their knowledge of Western — not of Eastern — natures, lay down the laws for our guidance. “

” My only wish is to get into Parliament in order to compel the production of the whole of the correspondence which I had with the F.O. since I came to China, and which will show whether or not I have been a missionary of peace, a representative of justice and honour, turning neither to the right nor the left. “

I will show what I have done for the extension of trade (Siam alone employs two hundred ships in a trade of my creation). I will show that I have governed this colony for years, and have not drawn a penny from the imperial treasury. Every one of my predecessors has been covered with honours. My labours have exceeded theirs tenfold. I can point to results it was never their good fortune to obtain.”

In November, after the arrival of Lord Elgin, he writes thus :

“My dear Sir Joshua,

” Thanks, many thanks for your favour of 5th October. Though I have now no responsibility as regards our present relations with China and our hopes for the future, yet, I am happy to say. Lord Elgin has endorsed my policy. I believe he came thoroughly impregnated with the views of the opposition, but he has found that to persevere in the course marked out by Cobden and Lord Stanley, he would have to disorganise and imperil the whole of our relations, and to transfer to the Emperor a guard which he left Yeh to settle as best he might. … ”

We give one more extract from a letter dated 29th March, 1858.

” As regards Canton, Lord Elgin found it necessary to carry out my policy, in order to save himself from vexation and disappointment, and to prevent a general war with China, which the reference to Pekin of the local question would probably have brought about. I always believed that the Emperor would not support Yeh, whose supporters are not among his own countrymen, who bitterly blame him, but in an ignorant House of Commons. As the Emperor of China acknowledges that Yeh was wrong, has disgraced and dismissed him, I hope those who condemned me will acknowledge their error. Do not suppose, however, that I approve of the policy now being pursued. I think a fatal mistake was made when Lord Elgin reinstalled the Chinese authorities in Canton. They are all intriguing against us, committing many atrocities, while in the Chinese mind the impression is left, that we are not masters of the city. “

” Then again, the Ambassadors are gone north, without having done anything towards the settlement of the Canton question, which in my opinion should have settled in the locality the indemnity provided for out of the local revenues, the lands appropriated which we want for the factories (under fair rentals).

These matters ought never to have been referred to the Emperor, who leaves invariably such questions to the local Mandarins. It is a sad pity that any foreign power should have been called in to influence our policy, which 1 would have distinctly marked out, and submitted not for discussion but co-operation.

The interests of Russia are wholly territorial; those of France, Catholic proselytism; those of America, to catch what she can at the least cost. I am persuaded had the matter been left to the admiral and me, it would have been arranged satisfactorily months ago, without the cost of a penny to the nation, and with grand results to our trade. . . .” (The rest of this letter is missing.) “