CHAPTER XXV. This chapter covers the mismanagement of the Crimean War; it is mostly in the form of letters between Josh and Richard Cobden. Both took a generally non-interventionist approach to European affairs, and their criticisms of the Army were political, in so far as the Army was still largely officered by the aristocracy. Officer’s commissions were still purchased at this point, rather than awarded by merit. It should be born in mind that both Joshua Walmsley II, and Hugh Walmsley were army officers, which possibly coloured Adeline’s views, who in Richard Cobden’s view ” sometimes takes too poetical a view of the glories of war.” But perhaps that’s the only way to cope with having two sons as serving soldiers.

Sir John Bowring mentioned at the end of the chapter was the fourth Governor of Hong Kong, had been Josh’s predecessor as M.P. for Bolton, and was the great-uncle of Adeline’s nephew Hugh Mulleneux’s wife Fanny Bowring Mulleneux.

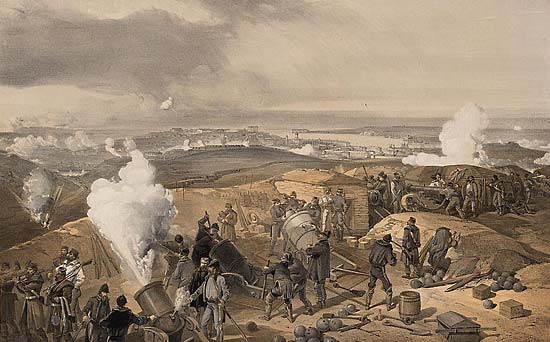

As the winter of 1854-55 drew on, the nation realised in its full force the meaning implied in the phrase that we had ” drifted into war. “ In the spring a gallant army had left her shores. In September, letters reached home, complaining that the changeable climate of the Crimea was unprovided for. Then followed reports increasing in gloom with the shortening days, of troops dying of disease and want

Hearts in English homes sickened during that bitter winter at the pictures drawn by ” our own correspondents “ in the Crimea, of the condition of the sick and wounded. In imagination the nation beheld ” that bleak range of hills “ overlooking the Black Sea, where — ragged, shoeless, overworked, racked by disease in want of food, shelter, fuel — the remnant of its army was dying at the rate of ninety or a hundred per day. Seven miles distant the English held a port stored with every necessary provision and means of relief; but the road to it was made impassable by snow, which, combined with the pedantic delays of red-tape-ism, frustrated all efforts to bring comforts to the soldiers, ” I shall never forget the gloom of that winter, “ says Sir Joshua, ” when each man asked the other with whom did the fault lie, was it with the commanders abroad or with the Government at home ? “

” Excitement was at its height when Parliament opened on the 23rd of January [1855]. On the first night, the Earl of Ellenborough and Mr. Roebuck gave notice that on the 25th they would bring the conduct of the war under critical review. That night the country was taken by surprise by the resignation of Lord John Russell, who explained this unusual, if not unconstitutional step, by alleging that he could not resist Mr. Roebuck’s motion. The accounts that came from the East were ‘ horrible and heartrending,’ and ‘ with all the official knowledge to which he had access, there was something inexplicable in the state of the army.’ “

” He explained that during the recess, he had urged Lord Aberdeen to appoint Lord Palmerston to the Ministry of War, in the place of the Duke of Newcastle, a course the Prime Minister had refused to follow. When in the hour of reckoning Lord John Russell thus separated himself from his colleagues, the conviction deepened in the minds of all who heard him, that culpable negligence could alone explain the cruel fate of the army in the Crimea. “

“ Roebuck was suffering in health on the night he brought forward his vote of censure on the conduct of the war. The emotion that overwhelmed him, the weakness of illness made him almost inaudible; what, he asked, was the condition of the army before Sevastopol, and how had that condition been brought about ? In faltering accents he told how an army of fifty-four thousand men had left England a few months previous ; this army was reduced to fourteen thousand, of which only five thousand men were fit for duty. What had become of the forty thousand missing? Where were our legions ? A stormy and angry discussion followed Roebuck’s motion. Ministers and their supporters opposed the inquiry as dangerous and useless, but the House, dividing, by a large majority declared in favour of the motion. In the face of this overwhelming vote of censure, ministers resigned. ”

They resigned on the 1st of February. Then followed a fortnight during which the country was left without a Government — a fortnight of cruel suspense, as it anxiously watched the protracted negotiations to form a ministry capable of making head against the national calamity. In this fortnight are dated some vigorous letters addressed by Sir Joshua to The Atlas newspaper, showing up the series of blunders committed since the landing of the army at Varna, maintaining that the aristocracy are not business men.

He wrote : ” And it is a man clear-sighted, clear-brained, quick to resolve and act, unshackled by the trammels of red-tape-ism, that is wanted at this juncture. ”

” I have read your spirited letter in The Atlas “ writes Mr. Cobden. ” It is a pity that our quarrel with the aristocracy does not spring from some other cause than the complaint that they don’t carry on war with sufficient vigour. ”

On the 16th of February [1855], the Cabinet was formed. It was a reconstruction of the former ministry, and included no new members. On Lord Palmerston, who had replaced Lord Aberdeen as Prime Minister, centred the nation’s hopes for the better management of the war. Lord Panmure was made Secretary of War in the place of the Duke of Newcastle. This change in the administration did not induce the House to rescind its vote in favour of Mr. Roebuck’s motion. The nation would not be put off; with passionate reiteration it demanded : ” What has become of our forty thousand missing soldiers of the army of fifty-four thousand that left our shores some months ago ? ”

The House of Commons persisting in the inquiry, another ministerial crisis occurred. On the 22nd of February, Mr. Gladstone, Sir James Graham, and Mr. Sidney Herbert resigned giving as reason that they had accepted office in the belief that Lord Palmerston would continue to oppose the formation of a Committee of Inquiry. They regarded this inquiry as unnecessary, unjust to officers, and dangerous. These vacancies in the Cabinet being filled up by the appointment of Sir Cornewall Lewis and Lord John Russell, the committee was appointed.

A few months later, its revelations justified the fears and suspicions of the nation. It showed that the Government had drifted into war unprepared, regardless of the difficulties and complications inherent to a struggle carried on at a distance. We sub- join the following extracts from a letter written by Mr. Cobden upon the fall of Sevastopol, and dated Midhurst, 27th September, 1855, showing up but too plainly the lamentable military mismanagement and failures that threw discredit upon the English arms in the Crimea.

After referring to a private circumstance relating to the death of a friend, and stating the general feeling of the moment, he proceeds :

” The French have covered themselves with great glory. I am sorry to say nothing but discredit and shame attaches to us; but as everyone speaks out, no doubt you will hear something of it at home. They may blame the men as much as they like ; I blame the system — a system which gives no encouragement to a man to discharge his duty — a system which has not only allowed but encouraged a crowd of officers to slink home on every possible pretence, from the Duke of Cambridge and Lord Cardigan downwards, and to leave, as substitutes for officers who know their men and were known by them, a parcel of mere boys from England, all anxious to come out because they had not the most remote idea what they were coming to. “

” My friend should have added that the men as well as officers who have gone out are mere boys. In fact, the recruiting-sergeant has been successful only in kidnapping children. The manhood of the country has contented itself with voting strong resolutions at meetings, making courageous speeches, or preaching inflammatory sermons; whilst the fighting has been left to unfledged striplings. It makes me indignant beyond expression to find my country exposed to the taunts of the world, as the cowardly bully amongst nations, always ready with the big threat, but skulking from the post of danger. Were I despotic, the first thing I would do should be to seize every newspaper editor, every orator, and every preacher I could prove to have fanned the flames of this war, and pack him off to take part in it until peace was arranged. “

” In sober seriousness, if we are to take a part in military operations on the Continent alongside of France, Russia, and the great powers of Europe, and if we would avoid the disastrous and ridiculous failures which we have witnessed, we must, like them, be prepared to submit to the conscription, by which a guarantee will be afforded that the interests and honour of the country are confided to a fair representation of the manhood of England. “

” As it is, we may fairly assert that the middle class, who, at least in West Yorkshire, are the most zealous advocates of the war, have taken no part in it. They form no part of the rank and file of the army, and, generally speaking, are only to be found as exceptions amongst the commissioned officers. When the operations of the war come to be calmly reviewed, it will be found that our sufferings and disasters have sprung almost entirely from our having started with pretensions to be on an equality with France, and having failed first with the numbers and at last in the quality of our troops. Lord Raglan himself stated that the terrible losses of last winter arose principally from our men having been overworked, the result of their inadequate numbers. And General Klapka, in his book on the war, says that the British, in spite of their heroic courage at Inkermann, would have been driven into the sea by the overwhelming numbers of Russia if the French had not come to their rescue : the small army of men which went out last year having been dribbled away, and mere boys sent to replace them. “

” The foregoing extracts from my friend’s letters will be interesting to my good friends your companions; but the following description of what he saw when he entered Sevastopol, I send exclusively for Lady Walmsley, who sometimes takes too poetical a view of the glories of war. “

“ On the Monday after the evacuation there was a flag of truce, and a steamer crossed to take away some wounded men left in one of the dockyard store-houses, which, as being rather out of fire, had been used as a hospital, I happened to be down on the spot at the time of the removal, and such a sight I never witnessed and hope I may never witness again. Hundreds of men, wounded in every conceivable maimer; some with amputated, some with broken limbs, some writhing in agony with musket-bullets in their bodies. All more or less neglected for many hours, were carried out of the wretched place in which they had been hurriedly placed, and were laid on the decks of the steamer for conveyance to their countrymen. The scene in the building itself was something awful, it was literally one huge mass of dead and dying men — belts, canteens, military equipments and dress, cut or taken from the men as they were brought in, were strewed about; and in many instances dead and putrid bodies lay over those still having a gasp of life left. “

” Anything more utterly shocking I cannot conceive. A huge tub passed me, under which two men staggered. Its contents consisted of arms, legs, feet, hands, and other parts of the human body. I know not what selection the Russian steamer could have made from the hideous mass, but when she had got her cargo she left, and next morning she was sunk with the rest. I passed the place again yesterday, and all around was still one mass of dead bodies in every stage of decay. The smell was frightful, and the sight of those dead bodies, swollen and blackened as they were, was worse. The whole place is a mass of putrefying human flesh. It is impossible to exaggerate the horrors which meet one at every turn. Determined not to leave anything in our hands that they could destroy, they actually hurled their field-guns, horses and all, harnessed as they stood, into the harbour. It was a strange sight to see them as they lay, through the clear blue water.”

” With our united kind regards to all your circle, “

” I remain, very truly yours,”

“R. COBDEN.”

Let us give another letter from the same pen — the more interesting because of its application to our present position towards Russia — dated :

” Midhurst, 12th November, 1855.

“ My dear Walmsley,

” But, really, when I see the tone of the press, and the reports of such meetings as that in the City, where that old desperado, Palmerston, is cheered on in his mad career by his turtle-fed audiences, I am almost in despair. If our ignorant clamours for the ‘ humiliation of Russia ‘ are allowed to have their own way, look out for serious disasters to the Allies ! No power ever yet persisted in the attempt to subjugate Russia that did not break to pieces against that impassive empire. “

” Tartars, Turks, Poles, Swedes, and French, all tried in their turn, all seemed to meet with unvarying success, and yet all in the end shared the same fate. The Russians can beat all the world at endurance, and the present struggle will assume that character from this very day. The question is, who can endure the longest the pressure on their resources in men and money ? It is not a question of military operations; the Russians will retire, but they will not make peace on terms that will give any triumph to the English and French ; they will gradually retire inland upon their own supplies, where you cannot follow them, to return again if your forces quit their territory. In the meantime, high prices and conscription in France, and taxes, strikes, and heavy discount in England, will have their effect. And who can tell what the consequences may be in a couple of years ? We are exaggerating the power of a naval blockade, and the effect of the depredations we are committing on the coast of that vast empire, because we do not sufficiently appreciate the comparative insignificance of its sea-going foreign trade, as compared with its interior and overland foreign trade. An empire three thousand or four thousand miles square, with such vast river navigation, has resources, which we cannot touch, ten times more important than the trade we blockade. “

” The very fact of her having followed a higher protective policy, and thus developed artificially her internal resources, whilst it has no doubt lessened her wealth and diminished her power of aggressive action against richer states, has, at the same time, by making her less dependent on foreign supplies, rendered it easier for her to bear the privations which a blockade is intended to inflict. The more I think of the matter, the more I am convinced that the Western Powers, if they persist in their attempt at coercing Russia by land operations, relying on the effect of a blockade, will suffer a great humiliation for their pains. The only thing that could have given them a chance of success was the co-operation of Austria and Germany upon the land frontier of that empire. “

” This was the only danger dreaded by Russia, and hence her efforts to conciliate German interests ; for, as I said in the House, every concession offered by Russia has been to Germany, and not to the allies. However, it is no use reasoning on these matters, for reason will have little to do in the matter. It is a question of endurance, and time will show which can play longest the game of beggar-my-neighbour. “

” My friend Colonel Fitzmayor wrote to me on the 4th inst., on board the Ripon, off Southampton. He said he was going to Woolwich, to which place I immediately wrote him a letter, but have had no reply. He is perhaps gone to see his family, and may not get my letter for some days. I fear there is no chance of my seeing him here this week. When do you think of leaving Worthing ? I am sorry I cannot leave home to come and see you at present. With regards to all your circle,

” Believe me, truly yours,

“R. COBDEN.”

In February [1855], Sir Joshua lost his friend, Joseph Hume. During the closing months of his life, the old man complained often with pathetic petulance ;

” I am in a grumbling condition, because I cannot do as I used, and yet would fain still do. The will remains the same, but the flesh is weak. ”

To the last the progress of the Crimean War was a subject of keen and painful interest to him. He kept on hoping to the last he would recover sufficient strength once more to take his accustomed seat in Parliament, and help to procure a more wisely administered system in behalf of the soldiers’ welfare. Those closing letters are touching evidences of an undimmed spirit and a failing body. The 4th December [1854] is the date of a letter written in a more hopeful vein :

” My dear Sir Joshua,

” I shall now expect to see you on the 12th, if I continue as I am ; but I have had doubts whether I should in prudence be able to attend the meeting. The state of the war and of public affairs is such as to call for a grand meeting as to numbers, and, I hope, strong in the advocacy of future and speedy measures for the support of our brave country- men in the East. There is much in Kossuth’s speech that deserves serious attention, but the condition and plan of Austria is what has destroyed the policy that ought to have been adopted, to unite and rally the popular and free principles against the military and despotic, which really is the great point to look to. “

“The Governments of Germany remember 1848, and have their fears of reaction which, sooner or later, must take place. But at present the difficulty is great, and we must give all the help we can to overcome that difficulty. “

” Let me have a few lines with any news that you may think worth repeating, and to engage my thoughts until the 11th, when I propose to be in Bryanston Square with Mrs. Hume. ”

The intended journey to London was never accomplished. We find him on the 21st January, 1855, writing:

” I have decidedly improved the last two days. Although all was packed up, and the horses were ordered, I do not think I shall move for the week, unless some extraordinary occurrence shall compel me. I shall therefore hope for a line, if anything be worth attention. We have had two gentle falls of one inch and a half of snow each, and at this moment not a breath of wind. I have not been out of doors for four days, and a good pair of bellows would blow me over, and yet I have no pain to look to as the cause of all this. ”

The end was not far off On the 13th February Mr. Cobden wrote :

“ My dear Walmsley,

“ I wrote to poor, dear old Hume, some time ago, but when I was not aware that he was so very ill, and of course I expect no answer. I fear your apprehensions will prove too well founded. “

” Perhaps if he had retired from Parliament at the last election, and gone to Switzerland, or America, or to some new scene, with his family, he might have lived a few years longer. But he preferred to die in harness, and after all, life to him would have wanted more than half its charms, if he had abandoned Parliament. May Heaven smooth the pillow of the glorious old man. ”

On the 20th of February [1855] he died. In him the Reform party lost its oldest leader, and the country the man whose keen, firm sense of justice and indomitable resolution had raised a standard of integrity, and established principles of order and economy, that made a mark that can never be effaced on the public administration of affairs.

On the 26th of February [1855], moving for a new writ for Aberdeen, Lord Palmerston paid a high tribute to Mr. Hume’s memory. Sir Joshua Walmsley, overcome by emotion, alluded, in a short speech, to the privilege he had enjoyed of possessing for many years the confidence and friendship of Mr. Hume.

“ It may be justly said that his unostentatious labours for the public good were only excelled by his private worth. Even in the arena of political strife, he never made an enemy or lost a friend. And I would indulge the hope that the representatives of a grateful people will not suffer services, at once so eminent and so disinterested, to pass away without some memorial worthy of them and of the country. ”

Sir Joshua Walmsley wished that a national monument, voted by both Houses of Parliament, should be erected to the memory of his friend. Mr. Cobden and many others approving the idea, it was taken up, and a requisition, signed by two hundred and twenty-four members of both Houses, was presented to Lord Palmerston, calling upon him to propose “ that a durable memorial be erected, by a vote of Parliament, to the memory of the late Mr. Hume, in testimony of the country’s grateful appreciation of his long, disinterested, and laborious public services. ”

But the proposal was silently defeated, on the plea that there was no precedent for it, that Joseph Hume had never been in office. A few hundred pounds subscription endowed a scholarship in the London University. Sir Joshua, keenly felt this rejection of a national recognition of his friend’s services. ” What man, “ he would often exclaim, ” had done so much for the best interests of his country, devoting his whole life to strenuous, unflagging work, without fee or reward ? ”

Sir John Bowring, writing from Hong Kong, in September, 1856, to Sir Joshua, remarks: ” I think it sad evidence of an unsound state of things, that a man like Joseph Hume should have been allowed to live and die without other honours than those which individual esteem and gratitude brought to accompany him on his progress, and which now gather round his tomb. The appreciation of the fiercer parts of human character ; the warlike, the passionate, in preference to the gentle, the pacific, the permanently useful, is somewhat startling to those who desire the world’s improvement. We grieve, protest, but where shall we find a remedy ? ”

The following graceful tribute from the same pen, to the memory of Joseph Hume, we find enclosed in another letter :

Not of the crowd, nor with the crowd did he

Labour, but for them, with clear vision bent

On to reform, steadily he went

Onward, still onward perseveringly ;

Yet not a hair’s breadth from his pure intent

Diverted, or by frowns or flattery ;

His nature was incarnate honesty.

And his words moulded what his conscience meant ;

So, honoured most by those who knew him best,

Leader or link, in every honest plan

Which sought the advance of truth, the good of man,

Still scattering blessings, through life’s course he ran ;

And when most blessing others, then most blessed.

Till called from earth to heaven’s most hallowed rest