The reason the Callaghans feature is that Catherine Callaghan married James Joseph Roche who inherited Aghada from John Roche. So Gerard Callaghan, is James’ brother-in-law. He is, to use Noel Gallagher’s memorable phrase, “like a man with a fork in a world of soup.” and appears to be prize winningly obnoxious.

He was born c. 1787, the third son of Daniel Callaghan (d. 1824) of Sidney House and Mary Barry of ‘Donalee’; brother of Daniel Callaghan M.P. Of the six brothers, John and Patrick seem to have concentrated on business. Daniel and Gerard were MP’s, and the youngest two, Richard and George were a barrister, and a soldier respectively.

Gerard was the M.P. for Dundalk between 1818 and 1820. Dundalk was 200 miles away, and Gerard bought the seat from the Earl of Roden. The going rate for the seat was between £3,500 and £4,000. He was finally briefly elected as M.P. for Cork in 1829. He was also President of the Cork merchants’ committee.

The following is from his biography at the history of parliament online with some additions.

Callaghan, whose father had ‘made a fortune during the war’ supplying the navy in Cork, had been partly educated in England and become ‘affected in his manner and anglicised in his accent’. A ‘master of the principal modern languages’ and ‘a fair classical scholar’, his ‘liberal accomplishments and refined habits’ allegedly made him ‘too much of a fine gentleman for his brother traders in beef and pork’, among whom he acquired a reputation for a ‘sarcastic manner’ and ‘censorious wit’. In 1818, having renounced his family’s Catholicism and converted to the established church, he had purchased a short-lived berth at Dundalk ‘for a large sum’. Lord Hutchinson, whose family dominated the local gentry and returned one Cork Member, could ‘not see how it was possible to yield a certain seat to such a blackguard’ and privately considered him ‘an impudent, rash upstart’.

At the 1820 general election Callaghan offered for Cork, citing his ‘perfect acquaintance’ with its mercantile interests, in which he had ‘laboured and prospered’, and ‘strong attachment to the constitution’. Advising the Liverpool ministry whether to support him, Charles Arbuthnot observed, ‘He is a friend, but not very reputable, being a great stock jobber and always putting questions to … Vansittart’, the chancellor of the exchequer. After an ill-humoured five-day contest he conceded defeat, boasting that the prospect of the new king’s death would enable him to stand again ‘at no very distant period’. His remarks were denounced by Christopher Hely Hutchinson, one of the Members, who a few days later lost a finger in a duel with Callaghan’s younger brother Patrick. ‘The general feeling seems to be that Gerard Callaghan put his brother in the place he was afraid to take himself’, commented one observer. Reporting on his attempts to obtain support from ‘both parties’ in December 1820, Hely Hutchinson’s agent observed, ‘I think he has declined since the election. His measures are half or rather double measures, and his manners are intolerable, but he gains individuals by pecuniary accommodation’. It was expected that he would offer again at the 1826 general election, but in the event he declined, explaining that ‘many circumstances combine at present to determine me not to persevere’. The long-anticipated death of Hely Hutchinson a few months later created a vacancy, for which Callaghan came forward under the banner of ‘Independence and Protestantism’, stressing the need for a commercial representative and his aversion to any measure of Catholic emancipation that would endanger the ‘constitutional ascendancy of Protestantism’. Denounced by the Catholic press as ‘a kiln-dried and mendicant mongrel’, who had assumed Orange colours to serve ‘a personal object’, and threatened with violent reprisals for his ‘apostacy’, he demanded the immediate abolition of that ‘abominable nuisance, the Catholic Association’, the ‘honour’ of whose ‘slander’ he shared ‘with some of the finest characters in the country’. In a letter surely intended for him but written to his Catholic brother Daniel, Peel, the home secretary, declared, ‘I heartily wish you success on account of the manliness and ability with which you have avowed your public principles’. It has been suggested that his family refused to support him on ‘public principle’, but at a pre-election dinner his eldest brother John refuted claims of a rift, saying it was “due to the memory of his father to say that … it was his practice … that they should … adopt that creed which seemed to them most consistent with … the dictates of their consciences … With regard to the course his brother had followed … nothing other than conscientious conviction had influenced him … and the principles he expressed were the very same which he had uniformly avowed since maturity.”

At the nomination, he caused ‘uproar’ by insisting that it was ‘morally impossible’ for those professing ‘all the principles’ of his former religion to ‘be perfectly allegiant to the state’.

After a violent ten-day contest, during which his cousin William Hayes fatally wounded one of his opponent’s supporters in a duel, he was defeated. Talk by the ‘violent Protestant fanciers’ of a petition came to nothing, Lord Hutchinson, who had succeeded as 2nd earl of Donoughmore, commenting that ‘he had already spent too much money, and … would not throw away a single shilling more’.

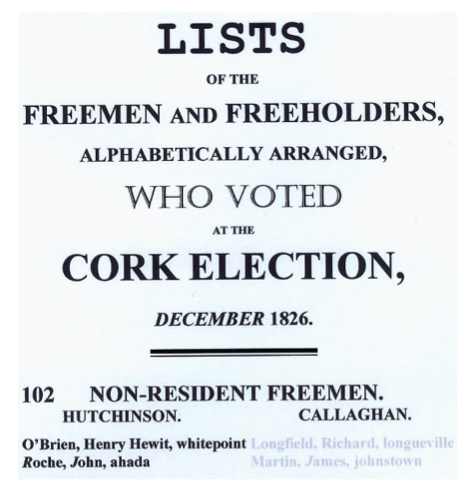

And from a family point of view, as can be seen by the voters list opposite, neither Henry Hewitt O’Bryen senior, nor John Roche voted for him despite Catherine Roche being gerard’s sister.

In September 1828 Donoughmore advised Lord Anglesey, the Irish viceroy, to ‘refuse’ a public dinner for him proposed by the Cork merchants committee, of which Callaghan was president: “I don’t know that there is anything to urge against Callaghan’s character. He is a coxcomb, but he has some parts, he has besides a very good landed estate and is the first merchant in Cork. Undoubtedly he turned first Protestant and then Orangeman … [but] I don’t think there is anything … which disqualifies him from being a competent chairman at a dinner given to a lord lieutenant … However, the Catholics and many of the liberal Protestants … [are] … furious at the notion of Callaghan being in the chair, and told me that no liberal Protestant and certainly no Catholic would attend.”

At a meeting of the Cork Brunswick Club on the eve of Catholic emancipation, 13 Jan. 1829, Callaghan insisted that the ‘only Protestant security’ was ‘in Protestant ascendancy’ and warned that the ‘hidden hand of Popery’ was ‘aiming at … a counter-reformation’, ‘an evil’ which could only ‘be grappled with and dealt with fearlessly by a Protestant Parliament’. On 3 Apr. Peel apologized for not replying sooner to his letters of 12, 14, 16 Mar., but explained that ministers had not deemed it ‘advisable’ to extend the Irish franchise bill to borough freeholders. That month Callaghan became connected with a ‘slanderous rumour’ given the ‘highest publicity’ in the press, that Anglesey’s daughter Lady Agnes Paget had had an affair with a member of the viceroy’s household, become pregnant and refused to consummate her subsequent marriage to George Stevens Byng. ‘The calumny’, reported The Times, was ‘traced to … a bitter Brunswicker’ noted for his ‘flagrant hostility’ to the ‘rights of those from whose community he has apostatized’. An action was brought against him by the Pagets, who engaged Daniel O’Connell and John Doherty, the Irish solicitor-general. At the Cork assizes that summer, Callaghan’s counsel admitted that ‘from foolish credulity’ his client ‘had been made the dupe of declarations’ which were ‘utterly false’, and Callaghan ‘expressed in the strongest terms his regret’ and ‘disclaimed altogether having been influenced by political feelings towards any of the parties concerned’. The case went no further, Byng telling Anglesey: “All our counsel, with the exception of O’Connell, are more than satisfied with the result, and consider it more triumphant than having damages awarded, an issue extremely problematical, when one considers that Callaghan was on his own dunghill and had excited on his behalf a strong political party feeling, and that all the jurors with one solitary exception were notorious Brunswickers, and at the last election, had to a man, given their votes to Callaghan.”

On 28 Aug. 1829 O’Connell complained to his wife that Doherty ‘gave up the case upon a most miserable apology’, adding, ‘if your husband had been conducting the cause it would have been otherwise … Callaghan has had a decided triumph’.

The previous month Callaghan had came forward for a vacancy at Cork on political principles as ‘fixed as they were in 1826’, warning that emancipation rendered it ‘more than ever necessary to guard our Protestant institutions’ and prevent ‘further encroachments’. ‘The conduct of Callaghan about Lady Agnes must make it impossible for any gentleman to support him’, observed the Duke of Wellington, the premier. A fortnight before the nomination he was charged with breaking an agreement to comply with the decision of a committee and retire in favour of an opponent. Lord Beresford, who had brokered the deal, protested that he followed up his ‘first ungentleman-like act by a strong and active canvass’, “forcing the other candidate to withdraw, whereupon I felt that Callaghan’s conduct … required some admission of its baseness, some reason for its adoption, and I required it of him. I enclose you his answer. It is but a bad satisfaction for what he has done, but … it admits of his having behaved so ill … and he said before many he was ashamed to look me in the face.”

‘Callaghan has behaved like himself, i.e., like a great scoundrel in the transaction, but I fear there is no chance of excluding him on this occasion, though I trust his defeat on any other … will be certain’, Lord Francis Leveson Gower, the Irish secretary, informed Peel, 3 July. Attempts to find an opponent came to nothing, and he was returned after a token three-day contest got up by the Cork Liberal Club without their candidate’s sanction. ‘I have at last attained the object of my ambition’, he declared at his chairing, adding that a petition against his return on the ground of his being ‘a government contractor’ would come to nothing, since all his contracts had ‘been completed’. On 15 Sept. 1829 Leveson Gower asked Peel “what you would wish to have done in the matter of Gerard Callaghan. If you wish to turn him out of his seat, I believe you have nothing to do but to extract from [John] Croker and forward to Ireland a copy of his contract with government. If you think this proceeding rather infra the dignity of government the consequence will probably be the same, as I do not imagine you will … oppose the production of that document should it be moved for, as it will, in Parliament.”

Peel replied, ‘We had better leave Callaghan to his fate. We could do nothing until the meeting of Parliament. If Gerard be a contractor, he has … little hope of escaping detection, and if he be not, it will be as well that we have not stirred the inquiry’. Callaghan took his seat, 8 Feb. 1830. On 12 Feb., in a ‘very extraordinary’ interruption to the tabled motion, he commended ministers for their conduct over Portugal, complained that the withdrawal of £1 notes issued by private bankers had led to ‘great distress’ and a ‘scarcity of money’ for ‘objects of great importance’, advocated further civil list and tax reductions, but found himself unable to speak as intended ‘on the subject of Ireland’, owing to the ‘impatience’ of the House. . On 3 Mar. 1830 he was unseated on petition after an election committee concluded that his contract to supply the navy with 13,000 tierces of meat ‘had not been completed’. (There was a clause that his ‘beef and pork should be good, sound and sweet for twelve months’ after the ‘last delivery’, which had occurred on 28 May 1829.) His application to be released from his contractual liabilities in order to stand again was unsuccessful. Speaking in support of his brother Daniel’s candidacy in the ensuing by-election, he remarked, ‘I feel it my duty to apologize to you, and I now solemnly declare that when I solicited your suffrages, I was unconscious of my ineligibility’. At the 1830 general election he declined to stand after a committee of family friends determined that Daniel, whom government were disposed to support, had the ‘best chance of success’. A last minute attempt by the Cork Brunswick Club to effect Daniel’s withdrawal and bring in Gerard unopposed came to nothing.

Callaghan, who reputedly followed Daniel in supporting the Grey ministry’s reform bill, died ‘suddenly’ in February 1833, after an ‘unfortunate surgical accident’. The Tory Cork Constitution eulogized him as ‘one of the moving springs by which the life, spirit, and enjoyment of society in this city, were replenished’, but a fellow Orangeman recalled in his diary that ‘he had a readiness and often times a smartness which led him into scrapes and made him give offence where none was ever intended’. ‘Infatuated with ambition … he stooped to an alliance with vulgar fanaticism solely for ambitious purposes’, observed a biographer fifteen years later. He was buried in the Catholic family vault at Upper Shandon.