THE DAILY NEWS, TUESDAY, JUNE 19, 1855 (London)

A singular minor case, involving charges of cruelty against a guardian, was adjudicated on by the Master of the Rolls, on Saturday. The question was, whether the guardian of the minor should pay the costs of the proceedings that had been resorted to to remove the minor from his care.

Paulina Roche, the minor in the case, is the daughter of the sister of Dr. John Roche O’Bryan (sic) and Mr Robert. H. O’Bryan (sic) of Queenstown, Cork. She (Mrs Roche) died in 1836, at which period the minor was only eleven months old. She was left by her mother to the care of Dr O’Bryan (sic), of Clifton, Bristol, and a maintenance was allowed him for her support, which was increased from time to time, till it amounted to £ 139 per annum. She was entitled to a fortune of £10,000, the greater portion of which (£7,000 or £6,000) had been realised. Miss Roche was a young lady whose constitution was delicate, and therefore, it was contended she required great care and attention, instead of which she was provided with bad food, bad clothes, and was deprived of such necessaries as sugar and butter; she was likewise deprived of horse exercise, which was indispensable to her health. A pony, the bequest of a dying patient, was given to her; and when she was deprived of this a carriage horse was procured, which kicked her off his back, and she refused ever again to mount him. She also complained that upon two occasions he (guardian) beat her severely – that he made her a housekeeper and governess to the younger children, that he led her to believe she was dependent upon his benevolence; and further, that she was not permitted to dine with him and his wife, but sent down to the kitchen with the children and the servants. Having endured this treatment for a long period, she fled from his house in the manner hereafter described. To these charges, Dr O’Bryan (sic) replied that he had treated his niece with kindness – that her preservation from consumption was solely ascribable to his judicious and skilful treatment – that he caused her to be well educated – had given her many accomplishments, and a horse to ride, which was not a carriage horse, but an excellent lady’s horse – that she upon two occasions told him untruths which required correction, and that he would have punished his own children much more severely. He also relied upon the affidavits of friends (Mrs and Miss Morgan, Mrs Parsons, and the affidavit of his own wife) which represented that his conduct to the young lady was uniformly kind, and that from their knowledge of him and the course pursued towards her, they could vouch that no hardship or cruelty had been practised towards her. It was likewise contended that she would have better consulted her own respectability and displayed better taste if she had abstained from taking proceedings against her uncle and guardian, with whom she had been for so many years.

The Master commented severely on the conduct of the guardian, and said he was clearly of opinion at present that he should bear all his own costs; but whether he would make him pay the cost the minor’s estate had been put to in investigating these transactions, he would reserve for future consideration.

Dublin Evening Post June 1855

ROLLS COURT – SATURDAY JUNE 16 – EXTRAORDINARY CASE

In re Paulina Roche

This was a minor matter, the question at present before the court being whether the guardian of the minor should pay the costs of proceedings consequent upon an alleged system of cruelty practised towards her. The facts of the case will be found fully set forth in the judgement of the court, which, under the circumstance, is the best source from whence to take them. An outline at present will therefore suffice. The minor, Paulina Roche, is the daughter of the sister of Dr John Roche O’Bryen, and Mr Robert H. O’Bryen of Queenstown, Cork. She (Mrs Roche) died in the year 1836, at which period the minor was only eleven months old. She was left by the mother to the care of Dr O’Bryen, of Clifton, Bristol, and a maintenance was allowed him for her support, which was to increase from time to time, till it amounted to £ 139 per annum. She was entitled to a fortune of £ 10,000, the greater proportion of which (£ 7,000 or £ 6,000) had been realised. Miss Roche was a young lady whose constitution was delicate, and therefore it was contended she required great care, and attention, instead of which she was provided with bad food, bad clothes, and was deprived of such necessaries as sugar and butter; she was likewise deprived of horse exercises which was indispensable to her health. A pony, the bequest of a dying friend, was given to her; and when she was deprived of this, a carriage horse was procured, which kicked her off his back, and she refused ever again to mount him. She complained that upon two occasions he (the guardian) beat her severely – that he made her a housekeeper and governess to the younger children – that he led her to believe she was a dependent upon his benevolence – and further, that she was not permitted to dine with him and his wife, but was sent down to the kitchen with the children and the servants. Having endured this treatment for a long period, she fled from his house in the manner hereafter described. To these charges Dr O’Bryen replied that he had treated his niece with kindness – that her preservation from consumption was solely ascribable to his judicious and skilful treatment – that he caused her to be well educated, had given her many accomplishments and a horse to ride, which was not a carriage horse but an excellent lady’s horse – that she upon two occasions told him untruths which required correction, and that he would have punished his own children much more severely. He also relied upon the affidavits of friends (Mrs and Miss Morgan, Mrs Parsons, and the affidavit of his own wife), which represented that his conduct to the young lady was uniformly kind, and that from their knowledge of him and the course pursued towards her, they could vouch that no hardship or cruelty had been practised towards her. It was likewise contended that she would have better consulted her own respectability and displayed better taste if she had abstained from taking such proceedings against her uncle and guardian with whom she had been for so many years.

Mr Hughes Q.C. and Mr E. Litten appeared as counsel for Mr. Thomas Keane, the next friend of the minor. Mr. Deasy, Q.C., and Mr Lawless, for the respondent, Dr O’Bryen.

The MASTER of the ROLLS said that a petition was presented by Mr Orpin, the solicitor for the minor, for the purpose of removing the late guardian for misconduct. His lordship made an order on that occasion to the effect that the minor should reside within the jurisdiction of the court, which was indirectly removing her from the protection of the late guardian. The matter then went into the Master’s Office, and the late guardian very prudently withdrew from his guardianship, but although he had done so, he placed on the files of the court an affidavit, which he (the Master of the Rolls) had no hesitation in saying was a most improper affidavit to have filed, and which rendered it impossible that inquiry should cease as long as it remained unanswered. The general nature of the charge against the late guardian appeared to be this – that although he was allowed from 1850 a maintenance of £139 per annum, this young lady was not properly clothed – that she had not been properly fed – had been most cruelly treated and subjected to personal violence. Six or seven years ago she was actually driven to run away, which of course she had since been obliged to repent, and even if she did get education it was the education of a poor relation of the family. The governess who was employed to educate her cousins swore, as he (the Master of the Rolls) understood, that if the minor did get education it was at the expense of the guardian, and that she gave her instructions as a matter of charity. This young lady was obliged to run away, and conceal herself in a neighbouring village, and no person who looked at the subsequent transactions could entertain a doubt but that she had been treated with cruelty. It was sworn by Mr Sweeny, a solicitor of the court, that he was ashamed to walk with her she was so badly dressed. The Master, in his report, found that if the minor, who was in her nineteenth year, at the period he was making his enquiries, dined with the servants, or if she kept their company, it was not under compulsions, but he (the Master of the Rolls) would be glad to know was that the mode to deal with a minor of the court. He believed the truth of her statement that although the governess, the younger branches of the family, and she dined in a room off the kitchen in summer, in winter, a fire not been lighted in it, they dined in the kitchen. It was perfectly clear to his mind that this young lady had been kept ignorant, up to a late period, of the state of her circumstances. The Master found, and it was actually admitted by the respondent, that he told her on one occasion her father had left her nothing; that she would be in the poorhouse but for his generosity. He (the Master of the Rolls) adverted to this circumstance for the purpose of asking this gentleman who struck this young lady, in delicate health, with a horsewhip for having told him, as he represented an untruth – what punishment he deserved for having told her the falsehood that her father had left her nothing? She had been absolutely kept in a state of servitude – admittedly not dining with her uncle and aunt, and admittedly dining in the room off the kitchen. She got half a pound of butter for a week, but no sugar or any of those matters which were considered by mere menials to be the necessaries of life. Having got dissatisfied with this state of things, she was anxious to know whether the statement was true that her father had left her nothing – whether she was entirely dependent upon her uncle, with whom she lived. On the morning of the 4th of May 1854, the transaction took place which led her to write the first letter to her uncle who was now her guardian. It appeared that one of her cousins brought her a piece of leather which the child had got in the study of the late guardian, but not telling her anything about it she asked her to cover a ball, and she did so. He interrogated her on the subject, and having denied she took the leather, he took his horsewhip and struck this delicate young lady a blow which left a severe mark on her back to the present day. His lordship then read the letter of the minor to her uncle in Cork inquiring about her father’s circumstances, and complaining bitterly of the treatment she had received, and stating that, though she was then nineteen years of age, she had no pocket money except a little which had been supplied by friends. His lordship continued to say that the facts contained in that letter were corroborated by the statements of the guardian himself. On another occasion, the minor being in the room with her uncle, his powder-flask was mislaid, and being naturally anxious about it, as there were younger children living in the house, he asked this young lady respecting it, but she laughed at his anxiety, and he struck her a blow, according to his own version, with his open hand, but after the blow of the horsewhip, he (the Master of the Rolls) was inclined to think it was with his fist as she represented. Another letter was written by the minor, in September, 1854, to her uncle John (sic) in Cork, which he enclosed to Mr Orpin, who adopted the course that he wished every solicitor would adopt who did not consider himself the solicitor for the guardian, but the solicitor for the minor, whose interest was committed to his charge. On the 9th of October a letter was written, by the dictation of this young lady, giving the most exaggerated account of her happiness, and this was alleged to be her voluntary act, though by the same post Mr Orpin received a letter from her stating that she was under the influence of her aunt when she wrote it. Ultimately, in the absence of her uncle, and late guardian, and apprehending his anger when he returned, she left the house and went to reside with her uncle John (sic) in Cork, her present guardian. A circumstance occurred when Mr Robert O’Bryen (sic) went to recover possession of his ward, which corroborated strongly the minor’s statement. When he was passing through Cork, she was looking out of the window and fainted upon seeing him – so much frightened was she at his very appearance. The conduct of this gentleman appeared to him (the Master of the Rolls) to be most unjustifiable – not to use a stronger expression – and Mr Orpin, the solicitor, was entitled to his costs, the payment of which he might have no apprehension, as this young lady, who was represented as having nothing, was the heiress to £ 10,000, left to her by her father. With reference to Mr Robert O’Brien (sic), he was clearly of opinion at present that he should bear all his own costs; but whether he would make him pay the costs the minor’s estate had been put to in investigating these transactions, he would reserve for future consideration.

THE LIVERPOOL MERCURY AND SUPPLEMENT. FRIDAY, JUNE 22, 1855

PERSECUTION OF A WARD IN CHANCERY – IN RE PAULINA ROCHE

This was a minor matter, the question at present before the Rolls Court, Dublin, being whether the guardian of the minor should pay the costs of proceedings consequent upon an alleged system of cruelty practised upon her. The minor, Paulina Roche, is the daughter of the sister of Dr. J. Roche O’Bryan (sic) and Mr Robt. H. O’Bryan (sic) of Queenstown, Cork. She (Mrs Roche) died in 1836, at which period the minor was only eleven months old. She was left by her mother to the care of Dr O’Bryan (sic), of Clifton, Bristol, and a maintenance was allowed him for her support, which was increased from time to time, till it amounted to £ 139 per annum. She was entitled to a fortune of £10,000, the greater portion of which (£7,000 or £6,000) had been realised. Miss Roche was a young lady whose constitution was delicate, and therefore, it was contended she required great care and attention, instead of which she was provided with bad food, bad clothes, and was deprived of such necessaries as sugar and butter; she was likewise deprived of horse exercise, which was indispensable to her health. A pony, the bequest of a dying patient, was given to her; and when she was deprived of this a carriage horse was procured, which kicked her off his back, and she refused ever again to mount him. She also complained that upon two occasions he (the guardian) beat her severely – that he made her a housekeeper and governess to the younger children, that he led her to believe she was dependent upon his benevolence; and further, that she was not permitted to dine with him and his wife, but sent down to the kitchen with the children and the servants. Having endured this treatment for a long period, she fled from his house in the manner hereafter described. To these charges, Dr O’Bryan (sic) replied that he had treated his niece with kindness – that her preservation from consumption was solely ascribable to his judicious and skilful treatment – that her caused her to be well educated – had given her many accomplishments, and a horse to ride, which was not a carriage horse, but an excellent lady’s horse – that she upon two occasions told him untruths which required correction, and that he would have punished his own children much more severely. He also relied upon the affidavits of friends (Mrs and Miss Morgan, Mrs Parsons, and the affidavit of his own wife) which represented that his conduct to the young lady was uniformly kind, and that from their knowledge of him and the course pursued towards her, they could vouch that no hardship or cruelty had been practised towards her. It was likewise contended that she would have better consulted her own respectability and displayed better taste if she had abstained from taking proceedings against her uncle and guardian, with whom she had been for so many years.

The Master of the Rolls, after going over the facts carefully, said – It is a satisfaction to know, although this young lady has been described as a dependent, and as one who has been rescued from a workhouse, that she is entitled to £10,000; and the question of costs of Mr Orpin is not a matter of so much importance; he will, of course, be indemnified for his expenses. There is no difficulty about my obliging Dr O’Bryan (sic) to pay his own costs; therefore I may as well relieve him from any trouble upon this head, should he consider that there is any use in applying to me to be exempted from the payment of these costs. The only question for me to consider is, whether I shall not oblige him to pay all the costs of the proceedings consequent upon his conduct to his ward.

The Tralee Chronicle Friday, June 22 1855

ROLLS COURT – SATURDAY

In the matter of Pauline Roche, a minor

The petition in this case was presented to compel the late guardian of the minor, Dr Robert O’Brien, of Belfast (sic) to pay the costs of certain proceedings which had been instituted on the part of the minor in the Court of Chancery and the Master’s Office. The facts of the case will appear from his lordship’s judgement. The general nature of the charge against the late guardian appeared to be this – that although he was allowed from 1850 a maintenance of £ 130 per annum, this young lady was not properly fed – had been most cruelly treated and subjected to personal violence. This young lady was obliged to run away, and conceal herself in a neighbouring village, and no person who looked at the subsequent transactions could entertain a doubt that she had been treated with cruelty. It was perfectly clear that this young lady had been kept ignorant up to a late period of the state of her circumstances. The Master found, and it was admitted by the respondent, that he told her on one occasion her father left her nothing; that she would be in the poor house but for his generosity. His lordship then read the letter of the minor in cork, inquiring about her father’s circumstance, and complaining bitterly of the treatment she had received, and stating that, though she was then 19 years of age, she had no pocket money, except a little which had been supplied by friends. Another letter was written by the minor in September, 1854, to her uncle John in Cork, which he inclosed to Mr Orpin who adopted the course that he wished every solicitor would adopt, who did not consider himself solicitor for the guardian, but the solicitor for the minor, whose interest was committed to his charge. Ultimately, in the absence of her uncle, and late guardian, and apprehending his anger when he returned, she left the house, and went to reside with her uncle in Cork, her present guardian. Mr Robert O’Brien (sic) went to recover possession of his ward, which corroborated strongly the minor’s statement. When he was passing through Cork, she was looking out in the window, and fainted upon seeing him – so much frightened was she at his very appearance, the conduct of this gentleman appeared to him (the Master of the Rolls) to be most unjustifiable – not to use a stronger expression – and Mr Orpin, the solicitor, was entitled to his costs for the payment of which he might have no apprehension as this young lady, who was represented as having nothing, was the heiress to £ 10,000 left to her by her father. With reference to Mr Robert O’Brien (sic), he was clearly of opinion at present that he should bear all his own costs; but whether he would make him pay the costs the minor’s estate had been put to in investigating the transactions, he would reserve for future consideration.

THE BRISTOL MERCURY, AND WESTERN COUNTIES ADVERTISER, SATURDAY DECEMBER 29 1855

DR. O’BRYEN AND THE CORPORATION OF THE POOR

Audi alterum partem,

To the Editor of The Bristol Mercury

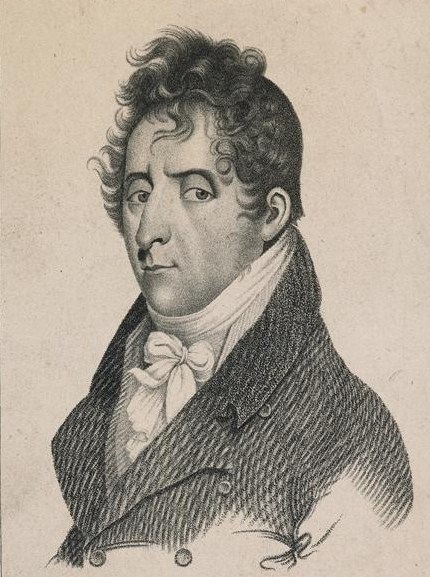

SIR – I need make no apology for asking your indulgence to enable me to defend myself by bringing before the public such explanation as I can offer of certain expressions that fell from the Irish Master of the Rolls when called on to settle a mere matter of costs. What purported to be his language appeared in your paper of the 22nd of June last. The course the Court of the Corporation of the Poor have thought proper to adopt, at their meeting of the 11th instant, obliges me, most reluctantly, to re-open a matter I had rather forgotten, not that I feel at all conscious of having done wrong, for, were it so, I would not now ask a hearing. The manifestly partial and one-sided import of the words used by the Master of the Rolls, it was considered, would be their own antidote, for all who knew me in private life were aware how unfounded such “surmises” and “inferences” as he thought it not beneath him to indulge in, were in fact. For this, amongst several other valid reasons, not adverse to myself, which I cannot publish, my friends advised me to let the matter rest, and I now regret that I permitted myself to be prevailed on to leave the matter to public opinion, which, it was alleged, would not fail to discern the ex parte nature of his language, and judge accordingly, instead of at once showing (at all risks) how entirely at variance it was with the judgement of the Master in Chancery, to which no exceptions were taken.

Before entering into the merits of this case, or making any justifications of my conduct, three points of special difficulty must be borne in mind: –

1st – By the manner of proceeding in the court of Chancery, charges to any amount, in number and gravity, may be made at pleasure, without regard to their truth or application, and I was called on to prove a negative, and that extending over a period of 18 years, not even illustrated by dates, to a long list of charges so got up.

2nd – I laboured under the great and irremediable disadvantage of the absence of the most important, I might almost say the only, witness capable of directly answering who had lived with me for eight years: she had left and gone on the Continent, to a situation, some time previously. The rules of the Court require all testimony to be sworn before a Master Extraordinary of that Court. None such being on the Continent, I was deprived of her evidence; my children at home were very young, the others were on the Continent at school, under age, and therefore inadmissible. Hence, to prove the negative, I was compelled to rely on my own and my wife’s evidence, that of any servant I could find who had lived with us during that period, and the very few visitors and friends who knew our private household life sufficiently well (and all know how few such can exist) to be able to speak to the untruth of one or more of these charges.

3rd – I have now, in addition, to contend with the “surmises” and “inferences” which the Irish Master of the Rolls thought proper to indulge in when called on to settle a mere matter of costs.

The Minor, Miss Roche, made certain complaints to the Lord Chancellor Brady, who directed that the Master in Chancery, J.J.Murphy, esq, should proceed to examine into and report upon them to him, which was done, and the report presented to his Lordship, when he directed the Master of the Rolls to settle the costs.

Every impartial reader of the reported language of the Master of the Rolls must be struck with one fact, that, to use a mild expression, he allowed the gravity of the judge to disappear in the one-sided earnestness of the advocate. It is manifest his language did not meet the justice of the case, and for this view I rely on the finding and judgement of the Master in Chancery, the officer to whom the complaints were referred, and before whom all the witnesses were brought, and the evidence was investigated, and within whose province it came to decide on the validity and effect of the allegations against me; and notwithstanding all the difficulties I had to encounter in rebutting these charges, and the almost impossibility of finding evidence, yet I refer the reader with confidence to his verdict.

“In the matter of J.P.Roche, a Minor, – Hy. Thos Keane, plaintiff, Hugh Roche and others, defendants; Hy. Thos Keane, plaintiff, Elizabeth Roche defendant; Hy. Thos Keane, plaintiff, Peter Cook and others, defendants.”

“ To the Right Honourable Maziere Brady, Lord High Chancellor of Ireland. May it please your Lordship, pursuant to your Lordship’s order mad into this matter, and in these tatises bearing date 2nd day of November 1854, whereby it was referred to me to inquire and report whether the treatment of the said Minor had been proper and according to the direction of this court; and for the purpose of ascertaining and determining upon the guardian’s treatment of the said Minor, I directed that a specification should be prepared, setting forth in writing the charges or causes of complaint alleged by her, or on her behalf, against the said John Roche O’Bryen: the same were accordingly specified and marked with my initials.”

The charges laid before the Master in Chancery for investigation, were as follows:-

FIRST GENERAL CHARGE

“ That said john Roche O’Bryen treated said Minor in a harsh and cruel manner, unsuited to he age and constitutional delicacy.” Viz:-

- “By striking her with a riding whip, and on other occasions making use of personal violence to her, and generally treating her with cruelty and harshness.”

- “ In having compelled her, or induced her by false statements as to her position in his family, to undertake and perform menial services, such as washing and dressing the younger children of said J.R.O’Bryen, acting as nursery governess, sweeping rooms, and like offices.”

- “In having compelled, or induced said Minor to dine in the kitchen or servants hall, in company with the female servants and younger children of said J.R.O’Bryen.

SECOND GENERAL CHARGE

“That said John Roche O’Bryen treated said Minor in a manner unsuited to her age and constitutional delicacy, and prospects in life, and not in accordance with the allowance made for her maintenance in that behalf by the reports on orders in said matter, viz:-“

- “In supplying her with clothes unsuited to her age and prospects in life.”

- “In supplying her with food unsuited to her station in life and natural delicacy of constitution.”

- “In not allowing said Minor pocket money suited in its amount to her age and prospects in life.”

- “In not providing said Minor with horse exercise, in accordance with the report bearing date 28th May, 1850.”

- “In having caused the acquaintances and teachers to believe that said Minor was a dependant on the charity of said John R. O’Bryen, and to act towards her accordingly.”

- “That said John Roche O’Bryen concealed from Minor her true position in his family, and made false statements to her respecting her prospects and the true position of her affairs.”

J.J.M.

The evidence on both sides having been entered into in respect to these charges, Master Murphy gave the following judgement to which no exceptions having been taken, it was formally embodied in his report to the Lord Chancellor, and to this I now refer, as my reply to the following charges.

“The 1st is sustained so far as to striking her with a riding-whip, and on another occasion (see evidence) striking her with his hand – no other proof of actual violence. It further appears the Minor at an earlier period (see evidence) felt such apprehension that she left her guardian’s house. &c. The striking I consider wholly unjustifiable, and I have no further evidence of cruelty. As to harshness, I think Dr O’Bryen’s manner may have laid a foundation to that charge. He appears to me to entertain very high notions of the prerogatives of a guardian as well as a parent, but I have no sufficient or satisfactory evidence of any general or deliberate harsh treatment on his part.”

“I have not evidence that satisfies me that Dr O’Bryen made use of false statements as to the Minor’s position in his family. The Minor may have undertaken and performed what are termed menial offices, which she now complains of, but in my opinion she never was induced or compelled to do so by Dr O’Bryen. I think she was, to an advanced period of her life, left too much in communication with servants, governesses, and younger children having regard to her prospects in life and her constitutional and moral tendencies and her due self-respect. This coarse, I think, latterly made her reckless and indifferent, and indisposed to avail herself of the opportunities which may then have been afforded her of associating with Dr and Mrs O’Bryen.”

“Upon the evidence before me I consider this a misrepresentation. I do not see any reason to believe that she ever dined in the kitchen – servants’ hall there was not in the house. If she ever dined in the kitchen, or in company with the servants, she did so, in my judgement, without any inducement or compulsion on the part of Dr O’Bryen.”

“The second I have already partially answered (see above).”

“I consider it due to Dr O’Bryen to state that whatever fault of judgement or manner he may be chargeable with in the moral treatment of the minor, he appears to have had her well educated according to her position and capacity, and to have bestowed on her medical treatment very commendable attention and skill, and that he also gave her full opportunities of taking horse exercise if she pleased; also latterly, opportunities, so far as she appears to have desired, of associating with his respectable acquaintances; and, with the exception of the article of clothing (about which I doubt), and the defects of moral treatment above referred to, I can discover no well-founded reason to complain of his conduct as a guardian.”

“The specific complaints under this band are:-

- “In the article of clothes, but for the evidence of Mr Stephen O’Bryen, having made a complaint to Mr Sweeny on this (unclear) as appears in the evidence of the latter, I should have found against the charge; after that evidence I am inclined to think there was some ground for the Minor’s complaint on this bead.”

- “As to the supply of food, it was not exactly what I could have wished in some respects; but it was always the same as that given to Dr O’Bryen’s own children; and it further appears that the Minor was allowed to keep the keys, and could have taken what she wished. I consider the cause of this complaint was much exaggerated.”

- “It does not appear that Minor ever asked or expressed a wish to get pocket-money. It also appears that she had actually given some money to Dr O’Bryen to keep for her.”

- “As to not providing Minor with horse exercise, I consider this charge colourable, and without any real foundation or just cause of complaint.”

- “The evidence on this point is conflicting: there is a good deal of it on the part of the Minor, but the charge has not been established to my satisfaction.”

- “This I have already answered as to the Minor’s position in his family. As to her prospects, and the true position of her affairs, Dr O’Bryen has himself stated that he did think it not prudent to disclose in this respect, with his reasons he may have withheld. I cannot satisfactorily arrive at the conclusion that he made any false statements in this regard. I must, however, state my belief that the minor was not, for a considerable time past by any means so ignorant of the state of her property and the condition of her affairs as has been represented on her part. And, upon the whole, I find that she has been maintained and educated in a manner which entitles him to be paid the allowance payable for said minor.”

J.J.MURPHY

The above official document fairly disposes, after a thorough investigation, of a long list of specified charges; but there remain a few new ones, brought forward for the first time by the master of the Rolls, and I will now proceed to deal with them.

It appears in evidence that the minor went daily to the house of a governess for a fixed time, and that this person thought proper, during this time to give her a few lessons on the harp, which she alleges she did without charge as she considered the Minor an orphan and dependant. This was done without the knowledge or consent of her guardian. The Master of the rolls found on this “an inference” and a grave charge. He says- “It appears to me that if she did receive a proper education, it was that of a poor relation, and my inference is, that the money was spent on the ducation of the cousins of Minor, and that the governess, from motives of benevolence, gave this young lady, whom she supposed a dependant, instructions with her pupils.” No charge of this nature was ever made by my opponents: but on the contrary, it was admitted that Minor had received as good an education as she was capable of; a view confirmed by the report of the Master as follows:- “ I deem it right to state, in justice to the said guardian, that he appears to me to have displayed very commendable attention and skill in the medical treatment of said Minor, and to have had her duly and properly educated, and upon the whole that she has been maintained and educated by him in a manner which entitles him to be paid the allowance payable for the said Minor.”

Again the Master of the Rolls indulges in inferences. He is represented to have said-“Now, if the Minor deserved punishment for a falsehood, what punishment would be sufficiently ample for the man who told his niece such a falsehood as that her father died in debt and left her nothing.” The facts of the case show the Master of the Rolls to have been ill-informed, and to have made a grave charge which he ought to have known was untrue in fact. The facts are these:- The father of Minor made his will in 1832 and died in 1835, when Minor was three months old. He left all his real and personal property to his brothers absolutely, save an annuity to his widow, and made no provision for any child or children. Master Goald’s report of 1836, when minor was made a ward, makes it appear that only £1374 remained in Irish funds out of £ 10,000 to which Minor was entitled under the will of her maternal great-grandfather, to whom her father was executor. Her father admits in his will that he drew and spent the money, and accordingly bills were filed against his brothers to recover deficiency. All the property was sold, and did not realise anything like the debt. Hence it was perfectly true to tell Minor that her father had left her nothing and died in debt.

That the letter of May 4th, 1854, written by Minor, was a part of a conspiracy, must appear to everyone, when I state that it was proved by several witnesses that the Minor knew she had property of her own, and was not dependant. Sympson, the man-servant who accompanied her when she rode out states in his evidence, “ Minor frequently told him when out riding with her, and he particularly recollects one occasion in the summer of 1851, and he heard her tell the other servants of the house the same thing, that she had property of her own, and that Dr O’Bryen was allowed for her maintenance, and also the keep of a pony for her use;” and the master has found, “I must, however, state my belief that the Minor was not, for a considerable time past, by any means so ignorant of the state of her property and the condition of her affairs as has been represented on her part.” So much for her alleged ignorance up to August 1855 which I am deeply grieved to say she has sworn to. In regard to the letter which this Minor has declared she wrote to Mr Orpen, at the dictation of Mrs O’Bryen, I will only say that Mrs O’Bryen has twice sworn that she only, as was her custom, connected the Minor’s ideas, and faithfully expressed her wishes at the same time without suggestion of her own, and I will add, we both now believe that she thus acted to deceive and put Mrs O’Bryen off her guard. The Minor took care to send to her solicitor the pencil sketch, which at least, demonstrates deep cunning. Again, this unfortunate child has sworn that on October 3rd 1854, when Mr Orpen called to see her, she was engaged sweeping out the school-room, and doing other menial work, while two persons clearly prove on oath that she was dressing to go out to pay a visit and not engaged as stated by her, and one of these witnesses was the servant, who was actually at the moment employed in these duties, who swore, “ saith that Minor hath not been, and was not employed in sweeping out the school-room, or making up her own room at the time of said Mr Orpen’s visit; inasmuch as this deponent was in the act of making said minor’s bed, dusting her room &c.2 Whilst said Minor was dressing to go out, saith “that whilst in said house Minor never swept out school-room, never made up her own room, or did any other menial service.” After this, what reliance can be placed on this Minor’s statement?

I will say one word as to dress. This minor so wilfully neglectful of her dress and personal appearance, that for several months Mrs O’Bryen declined to speak to her on the subject for when she did so she received an insolent reply. Hence I was myself obliged, if in the house, to inspect her daily before she went out and when she came down in the morning, and it rarely happened that I had not to send her to her room to change or arrange her dress, brush her hair, and often even to wash her face and neck. For a reason then unknown and unsuspected by us, but which has since transpired (viz:- her intention to found a charge and give it the appearance of truth), she would persist in only wearing old and worn-out dresses that I had several times made her lay aside, and directed to be thrown into the old clothes bag. In fact I had to threaten to search her room and burn them before I could succeed. She put on one of the worst of them outside the day she left my house. I often met her in the street, and had to send her back to change her dress, &c., and notwithstanding all this trouble, my wishes were evaded or neglected the moment my back was turned. The amount of vexation and annoyance this child gave us by her habits and general conduct cannot easily be described. Not a single article of dress was bought for her after Mr Orpen’s visit, and yet an excellent wardrobe was found in her room the day she left. The list is too long to add.

There is only one point on which the Master finds against me, viz. striking: on this subject I am unwilling to give details. It is quite true that in a moment of hastiness on two occasions (in 18 years) caused by extremely bad general conduct on the part of Minor, remonstrance having failed, which at these times was brought to a point, and I did strike her once each time as she was leaving the room, and of this, which in reality is nothing, much has been made by those who wanted to make costs, certain to be paid by either party.

My counsel in Ireland recommended an appeal, but my law adviser in this country said “What are you to gain? All material charges have been disproved; the master’s report is in your favour; no costs have been thrown on you; the allowance has been paid; would it be worth your trouble to appeal only to get rid of the language used by the Master of the Rolls? For this is all you could expect, while the expense of an appeal would prove considerable, and the trouble not a little.”

I will only add, in conclusion, that I hols certain instructions in Minor’s handwriting that she received from a gipsy, proving on the face of it that she was employed to act on this child’s mind.

I now submit the case, which I have shadowed(?) out in this letter, not so much in the hope of appeasing the unthinking anger of incompetent and prejudiced persons, as in the certainty of finding justice at the hands of all those who may have taken a very natural and justifiable interest in the allegations made against me, and are yet open to conviction, and are willing to give its just weight to a true and honest statement of facts.

It is a most painful position to be placed in, after many years spent in gratuitous and honourable professional service, to be summoned before a tribunal which has no power to acquit or condemn, but can only cast a stigma. But no man of earnest(?) and conscious rectitude chooses to withhold a defence beyond a certain limit, however strong his private reasons may be for so doing. That limit has now been reached in the opinion of friends and in my own, and I take with the utmost confidence the on course which appears left open to me.

“Fiat Justitia, ruat caelum”

Yours, &c, Mr Editor,

JOHN O’BRYEN, M.D.