CHAPTER XXIV. This is almost self-explanatory politics, and the drift into the Crimean War.

Through the autumn [1853], the National Reform Association abated no jot of its efforts. Whatever reforming energy, at this crisis, existed in the country, centred in that body. But the apathy of the nation was great in regard to every interest, save the absorbing one of watching the signs of the approaching conflict.

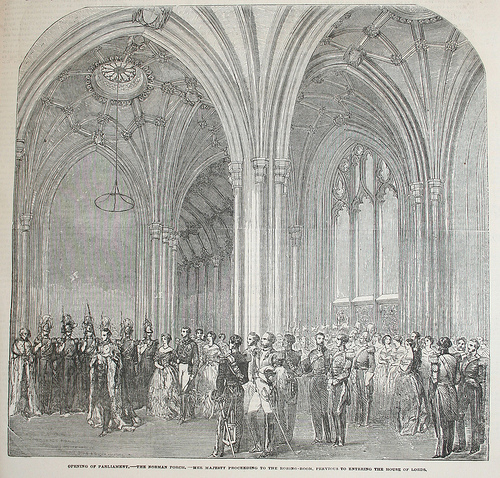

When the Queen opened Parliament on the 31st January [1854], the first paragraph of the royal speech announced the failure of the hopes entertained in August of a peaceful termination of the existing difficulties between the Sultan and the Czar. Another paragraph announced that a measure for the reform of the representation of the people would be laid before Parliament.

There was a certain grandeur in the attitude of a Government, which, amid the quickly gathering portents of war, could thus employ the interval on which such mighty issues depended with the reform of abuses in its own system. On the 13th February, Lord John brought forward his third Reform Bill. The exposition of this peaceful measure succeeded an animated discussion on the movement of the fleet and the provisions of the troops.

” Lord John Russell’s Bill of 1854, “ says Sir Joshua, “ was very different from the one he had laid before Parliament in 1852. The clumsy contrivances, the timidity that had marked the latter, were nowhere traceable here. “

” As clause succeeded clause, it became evident that a generous measure of reform was now offered to the nation. The six-pound borough franchise, hampered though it might be by an enforced municipal term of residence of two years and a half, would be almost equivalent in great cities to household suffrage. “

” The ten-pound country franchise would admit within the pale of the constitution all who were above the grade of the agricultural labourer. Various franchises were created, recognising the claims of education and the modest property of the thrifty. The principle of grouping boroughs, that had encumbered the proposed second Reform Bill, was abandoned, and in its stead was substituted the reduction in boroughs of less than five hundred electors from two members to one ; the representation thus withdrawn to be given to single unrepresented towns, or added to the representation of large constituencies insufficiently represented. This brief notice of the Reform Bill of 1854 will show that it was conceived in no narrow spirit. “

” It was calculated that it would enlarge by one-third the actual constituency in the country. By the six-pound franchise alone one hundred and fifty thousand of the working classes would be admitted to vote. True, the measure included no item of Mr. Hume’s yearly motion. The ballot was ignored. A distinct property qualification was still the requisite to citizenship. In all its bearings, however, it was calculated so materially to improve the working of the representative system, that, at my instigation, the Reform Association formally determined to give it hearty support. ”

But no Reform Bill could gain a hearing at that hour. The war, that for some time had been casting its shadow before, now became an actual and terrible reality. In March, the Queen’s message to Parliament announced the rupture of relations with the Czar. The second reading of the Reform Bill, previously fixed for the 13th of March, was deferred to the 27th of April. In the meanwhile, the nation’s professed indifference on the subject became more and more manifest ; all minor interests were swallowed up by tho absorbing one of the war, Since the night when Lord John Russell had explained the ministerial scheme to Parliament, only four spiritless public meetings had been held in its favour throughout the country ; only four petitions had been laid on the table, urging the House to persevere with it in spite of existing circumstances. The mind and heart of England were with its fleets in the Baltic and the Mediterranean ; with its departing armies ; and it had no care for other interests. An impatient feeling was growing up, demanding of ministers the withdrawal of a measure, the discussion of which the country was in no mood for at present; and upon which, if ministers were defeated, their resignation must follow ; and which, if carried, must involve a dissolution of Parliament, and the consequent ferment of a general election at a time when united action and vigilant watching of events were Parliament’s first duties. Still, to the queries as to the course Government proposed in relation to the Reform Bill, Lord John’s answers were evasive, revealing how keenly he felt his honour involved in redeeming the pledge he had given. On the 11th April, he yielded to the pressure of circumstances, and withdrew for the session the ministerial Reform Bill. The emotion that impeded his utterance in the closing passages of his speech, testified to the sharp conflict waged in his heart by a sense of conventional honour and the claims of a higher duty. The universal and hearty applause that greeted the announcement from all sides of the House showed that the sacrifice was understood and appreciated.

Friend and foe united alike to commend the act.

These exciting topics did not, despite the magnitude of the interests involved, outweigh the interest felt by Sir Joshua for the sufferings of the poor framework knitters of Leicester ; and here we pause to remark upon that noble trait in the character of the man that, ever true to himself, his heart was with the people of whom he never ceased to feel himself one. Neither parliamentary or municipal honours, increase of wealth, or advantages of social position, could for a moment render him unmindful of the working people, with whose feelings his own were identified.

And now that Mr. Cobden’s anticipation of a bad harvest had been realised, and that an almost universal scarcity prevailed throughout Europe, aggravating the anxieties of approaching war ; with dear provisions and heavy taxation, the condition of the unfortunate work-people of Leicester, encumbered by the frame- rent system, weighed heavily on Sir Joshua’s mind.

So strongly did he feel as to the course to be taken in this matter, that he refused to be influenced even by the opinion of Mr. Hume, whom he revered and loved above all men. ” Hume, “ he says, ” severely and utterly condemned as unfair and almost cruel the proposal by Parliament of any measure that might lead labourers to imagine that the law could interfere between workmen and masters. To this I would answer that political economy is not a one-sided science, that it recognises the claims of labour to be co-equal with those of capital. ” At the root of the fast-spreading evil — strikes — is a confused conviction that this balance is not justly upheld ; and until some mode of legislation is hit upon, whereby a fair solution of differences can be arrived at, this form of lynch-law will prevail. While, in this case, where penury and oppression prevented appeal to strikes, was it true political economy to allow an extensive and important manufacture to be sacrificed to the petty and arbitrary profits derived by individuals out of the hire of the necessary tool ?

In February [1854], Mr. Charles Foster moved for leave to introduce a bill to alter and amend the Truck Act, which had been passed in 1831, for the purpose of enforcing the payment of wages in money. The object of Mr. Foster’s measure was to provide against the many evasions of the law by making the Act more stringent. Mr. Foster’s bill passed a second reading, and was referred to a Select Committee.

Early in March, Sir Henry Halford introduced a bill, drawn up in conjunction with Sir Joshua Walmsley and Mr. Packe, to restrain stoppages from the payment of wages in the hosiery manufacture.

Sir Joshua appealed to the House to send the bill before a Select Committee. ” I have received numerous communications,” he said, ” from a number of persons connected with this trade ; and I can assure the House that all they desire is, that the whole subject should be fully and fairly investigated by a committee. ”

The second reading of this bill came off on the 22nd March [1854]. In a speech marked by deep feeling. Sir Henry Halford entered into many details depicting ” the distress, now grown to be proverbial, of the frame-work knitters of the Midland Counties. “ Sir Joshua Walmsley encountered the opponents of the measure, who maintained that it was contrary to the maxims of political economy. ” To inquire into the complaints of the industrial classes is not adverse to political economy. There is no free trade as respects frame-rents; the workmen must take the tools from those who give the work, and take them upon their own terms. “

After reading to the House letters addressed to him by operatives and employers : “ Both admit,” he showed, ” the evils that have grown up, although, I am bound to say, they do not all agree as to the remedy. For my own part, I do not take up the question as a pastime; I am impelled solely by the sincere wish to produce a better state of things than now exists. “ A majority of forty-seven decided in favour of the bill being read a second time. It was referred to the same Select Committee appointed to consider the bill brought in by Mr. Foster, for the amendment of the Truck Act. Of this committee Sir Joshua was a member.

The decision of the House caused some excitement in Leicester. Separate meetings were held by manufacturers, middlemen, and operatives, to appoint deputations to lay evidence before the House of Commons’ Committee. The manufacturers’ meeting was private. That evening in the Town Hall, the frame-work knitters assembled in temperate and orderly fashion. The half-starved men eagerly deprecated the expectation ascribed to them, that legislature could interfere with wages. They did not wish, as it was asserted they did, to confiscate property. They demanded only to have to pay a fair price for their frames. They asked to be protected, that was all. This was their answer to the political economy plea, the force of which they understood well enough. Mr. George Buckby was their spokesman. ” We will conduct the agitation, ” he said, ” in a good spirit, but at the same time with a determined opposition to a system fraught with mischief from beginning to end. ”

After detailing cases, the harshness of which it is difficult to conceive, the frame-work knitters passed a resolution thanking Sir Henry Halford, Sir Joshua Walmsley, and Mr. Packe for their endeavours to carry the bill through Parliament.

The Committee to inquire into the working of the Truck Act sat from the 15th of March to the 21st July [1854], and every day Sir Joshua attended its sittings. The inquiry, protracted so far into the session, allowed no time for the consideration of the question of the hosiery manufacture ; accordingly, the investigation of the frame-rent evil had to be postponed. The inquiry, however, was resumed in the following session, on Parliament granting Mr. Packe’s motion for a committee to be appointed to continue the work begun and left unfinished in the preceding year. From April to July this committee, of which Sir Joshua Walmsley was still an indefatigable member, inquired into the cause of the deplorable misery of the frame-work knitters. The evidence of many manufacturers, amongst whom that of Mr. Biggs, of Leicester, was conspicuous for its calm and earnest tone, condemned the system of frame-rent as ” the cancer in the hosiery trade. “

Mr. Biggs submitted a plan which he had adopted for years. In place of the usual custom of exacting full rent, whether slack time or illness impeded the knitter’s hand, he had substituted a system of deducting, for the wear and tear of his machinery, a certain ratio on the amount of work delivered in by the labourer.

This system the knitters liked, but the middlemen, as a rule, set their faces against it. The tale of the knitters was a simple and appalling statement of misery, out of which no issue seemed possible but a change in the system of exacting frame-rent. The evidence conclusively proved that whether it be in the power of legislation or not to effect a remedy, the hosiery trade was being sacrificed, and with it the interests of thousands of labourers, to the greed of the hirers out of the tool necessary for the manufacture. The report of the committee clearly indicated the conflicting currents in the trade and their fatal results. Parliament shrank, however, from the task, at once so delicate and so complicated, in attempting to reconcile under this new guise the claims of labour and capital, and again refused to interfere in the matter. The battle between manufacturers, middlemen, and labourers must be fought out by themselves, and so for the present the question of frame-rents was dropped by Parliament. The good work that had thus apparently failed bore its fruit, however. Popular opinion in Leicester condemned the iniquitous oppression. Manufacturers were stimulated to fresh resources by the ruin that menaced the trade, and middlemen themselves became less exacting. The knitters remembered who had been their advocate in the House; they knew Sir Joshua had upheld their cause even against his best friend and in their squalid homes his name became a household word.