CHAPTER XXIII. This chapter takes in the General Election of 1852 which resulted in the Tories having a majority of six seats. Josh had been elected an M.P. for Bolton in 1849, replacing John Bowring who had been appointed British Consul in Canton [ Guangzhou]. He exchanged that seat for Leicester in this election. Again all the family details are frustratingly small. We discover that Josh and Adeline take the two youngest daughters Emily, and Adah on holiday to France. It was an interesting choice of places to go, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte had seized power in a coup d’etat on the 2nd December 1851, and would go on to take the throne as Napoleon III on the 2nd December the following year, the forty-eighth anniversary of Napoleon’s coronation. The press were whipping up scare stories about a possible French invasion, and the Duke of Wellington died. The new Houses of Parliament were almost completed, and the new House of Commons was used for the first time. The State Opening of Parliament was the first time there was a Queen’s Speech from the current House of Lords.

The account of Sir Joshua Walmsley’s friendship and relations with M. Kossuth, which formed the subject of the last chapter, has forced us to forestall the date of this narrative. We shall now glance rapidly at the events immediately preceding the Crimean War, and give some letters of Mr. Cobden’s belonging to the period, which he characterised as the third panic.

Parliament was dissolved in the spring of 1852. Lord Derby, on the 24th of May, announced his intention of appealing to the nation, in order to decide finally on the question of Free Trade versus Protection. If at the coming election an unequivocal verdict should be given for Free Trade, he bound himself to throw overboard the principle of Protection, and forthwith adopt the policy that had hitherto only roused the rancour and vituperation of his party.

As soon as it was understood that a dissolution was imminent, and that the result of the election was to be regarded as the verdict of the nation on the question of Free Trade, the country prepared to pronounce that verdict.

These were the circumstances under which Sir Joshua Walmsley and Mr. Gardiner, in fulfilment of the pledge given to the Liberals of Leicester, on being unseated in 1848, presented themselves once more for election in that town. Mr. Wilde and Mr. Palmer opposed in the Whig interest ; but many proofs of loyal attachment from adherents and friends in Parliament cheered on the Liberals in the contest.

“ I do hope you may be returned, “ writes Mr. Hume to Sir Joshua, on the 17th June, “ by an overwhelming majority, as your defeat would be a loss to the cause of progressive Reform. I am, indeed, sorry to learn that those who have hitherto been known as Whigs, and considered to be promoters of efficient Reform, should oppose you who have given such assiduous and persevering support to the plan of Reform which with the sanction of one hundred and thirty-six of the sturdiest and best reformers of the day, has been supported by me for the last three years. “

Mr. Cobden also writes :

” Monday night House of Commons.

” My Dear Walmsley,

“ I have yours of this morning, and rejoice to find you in so hopeful and resolute a spirit. If energy, industry, and tact can win, I know you have enough of these essential qualities for an election contest, to put your opponents at the bottom of the poll. You must consider that there is far more than your own personal fate in the balance, for if you were defeated, it would undoubtedly be taken as a verdict from a free and democratic constituency against the principles which Hume and the rest of us advocate in the House. We have to-day got through the estimates, and everybody now says we shall have the dissolution on the 26th. Nobody seems to want any further delay. The ministerial party are not gaining anything by the longer postponement, and therefore I suppose we may consider the matter settled. ”

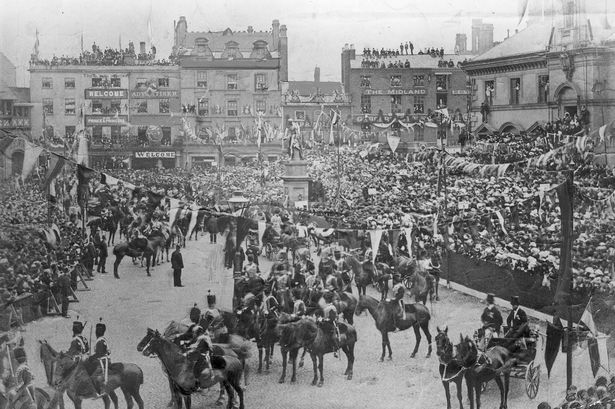

At Leicester, the nomination of candidates took place on the 7th. The polling began on the following morning. At each return of the poll, the Liberal candidates were declared to be at the head. By four o’clock the market-place was thronged with electors and non-electors, waiting to learn the final issue. When announced, it showed that by a large majority the Liberal candidates had won the day. ” Hearty enthusiasm greeted this announcement of our election, “ says Sir Joshua, “ and for the last time in the annals of Leicester, the victorious candidates were chaired and carried in triumph through the principal streets of the town. Illuminations and acclamations continued far into the night ; every sign of popular rejoicing hailed our election. The honour of the constituency was cleared. These demonstrations testified also to the feeling and convictions of the inhabitants in the question of Reform. ”

The result of the elections throughout the country unmistakably showed that the nature thus appealed to would brook no unsettlement or modifications of the laws passed in 1846-49, repealing the duties on corn, on sugar, and the old navigation laws. The nation once for all declared for Free Trade, and elected a Parliament to deliver its verdict.

The following letter from Mr. Cobden was received by Sir Joshua during a short tour on the Continent, taken immediately after the Leicester contest :

” Midhurst

“My dear Walmsley,

“We are rusticating in this quiet nook, to which I confess I become more and more attached, a proof, I suppose, of one’s declining energies.” [After some pleasant chat on home concerns, he passes on to the matters of political interest,] ” I do not think you have lost much, by not seeing the English papers since you left England. There has been quite a lull after the excitement of the elections. With the exception of a few dinners to successful candidates, and still fewer to unsuccessful ones, there has been no public stir. There is much speculation as to the future movements of parties and as to the probable ins and outs. But we have little to do with such combinations, and if Derby and Co. can shake off protectionism, I do not see why they may not give us as good practical measures as Russell or Graham. But I am in great doubt whether Dizzy [Benjamin Disraeli, who was the Chancellor] with all his ingenuity will contrive to doff his protectionist garment, and put on a Free Trade suit, without breaking up his party. There will be a score or two of the honest stupid men, who will not understand the word of command to ‘ wheel.’ In that case, I do not see how he can go on, for we are bound, as the first duty of the Free Trade majority, to have a distinct understanding that the Government gives up its protectionist hankerings. By getting rid for ever of the protective basis for the country party, we shall break up that country confederacy which stands in the way of all progress. But after upsetting the present Government, we shall be in no position to make a stable Government out of the opposition, for the chiefs will resist the ballot, and without that there can be no harmony or strength for the Liberals. I must tell you that the League, having a little money left, is employing Haly to collect together some of the facts connected with the intimidation, bribery, &c. of the late election, and although the League cannot use these facts for the purpose of advocating a reform of Parliament in the ballot, they will be very useful facts for others who can. Haly begins in the Isle of Wight, which is I believe a very strong case. I have heard nothing of Hume. He is, I suppose, in Norfolk, and most likely busy about Rajah Brooke. Fox is, I should hope, likely to be returned for Oldham. It is difficult to believe that the Radicals can be led by their leaders to vote for a Tory in order to spite Fox. By-the-way, I have this morning received a letter from Mr. Biggs, who tells me that his brother John is dangerously ill of fever, and that unless a favourable turn should take place he will be obliged to give up public life. Our harvest is in a critical state. It seems as if we are going to have another 1838. To-day I have not been able to leave the house. A drizzly rain has been falling without a breath of air. The wheat is sprouting in the sheaves, and a good deal of blight and mildew had shown themselves previously, so that even if we should have a sudden turn of fine weather, we cannot possibly have a good harvest. The corn will be in bad order, even if there should be an average quantity. This will be, to the farmers, a more trying season than they have had since 1846. “

” They will now see the full effect of Free Trade upon their interests. Formerly they could sell pig’s meat for human food, and the people had no choice but to take it at high prices. But now, with a free importation of good dry wheat from twenty countries, our farmers will be obliged to sell their sprout-wheat for no more than it is worth. This year will clear out many of the small farmers who are without capital, and it will go very far to put landlord and tenant upon a fair mercantile footing towards each other. The present turn of things in the agricultural world will not be in favour of Dizzy’s ‘ looming-in-the- future’ projects. He will be baffled in his hopes of reducing the interests on the Three per Cents. The revenue will sympathise with the bad harvest, and his agricultural clients will want a real relief, which their landlords will be forced to give them when they find that he cannot jump into a quart bottle to serve them. “

” In the end they will all come to my remedy — ‘a reduction of the expenditure ‘. You are right in saying that the Radical party have gained at the expense of the Whigs and Peelites. In fact the old Whig party is nearly extinct. They have lost all the agricultural counties, and the few county members who are Liberals go farther than the Whigs. If we take the ballot as a test, the whole strength of the Liberal party is Radical. And I do consider the ballot to be more and more the true test of Liberalism. The late election, particularly in the Irish counties, has brought to light more barefaced intimidation and coercions than ever were practised before. The extension of the franchise to the twelve-pound occupiers in the counties has brought a vast mass of poor dependent voters under the screw of the landlord and the whip of the priest. The scenes witnessed in that country have been pitiable and heartrending, and knowing that the ballot would be a perfect remedy against their recurrence, my blood almost boils with indignation at the puerile pretences with which it is resisted. And I have made up my mind that I will be no party to any measure for extending the franchise or rendering elections more frequent, until the ballot be secured, for it will only be, as in Ireland, diffusing through a larger portion of the people those sufferings and oppressions which are now practised upon a more independent part of the community. I should like to see a declaration agreed to that in no case should an election be allowed to take place in town or country, without an effort to find a candidate to contest it for the ballot, and to pay legal expenses only. Now is the time to respond to the general feeling amongst the electoral body upon the question. “

” And this is the moment too for impressing on our so-called Liberal chiefs that the party cannot be held together unless by the cement of the ballot. If they should contemplate appealing to the country with some scheme of parliamentary reform omitting, the ballot, there would be no response sufficient to overbear the opposition of the Lords. But this topic will keep until your return. The Parliament will not, I expect, assemble before the beginning of November. You and Lady Walmsley are doing well to take a long respite amidst the natural glories which now surround you. My wife joins me in kind regards to her and to all your family party ; and, believe me, “

“ Faithfully yours,

“RICHARD COBDEN.”

On the 14th of September the Duke of Wellington died at Walmer Castle, at the age of eighty-three. A burst of grief thrilled through the nation at the news that the great warrior had passed away from us. All that was remembered of him now was his ” life-long unflinching devotion to England.” In that moment of supreme gratitude his constant opposition to all reform — which, at one time, had alienated from him large masses of the people — was now forgotten ; there was memory only of the exploits of the general ” who had fought fifteen pitched battles, captured three thousand cannons, and never lost a single gun.”

The following letter gives Mr. Cobden’s appreciation of the Duke of Wellington ; and his apprehensions of the effect likely to be produced on the public mind by his death :

” Midhurst, 25th September, 1852,

*’My dear Walmsley,

“ We are glad to find that you and Lady Walmsley and the young people are safe at home again. You will find the apathy of the country upon public questions roused into a sudden paroxysm of emotion at the death of the old Duke. The Horse Guards and the aristocracy will not fail to turn this fever-fit to account ; but though the democracy join in the cry, I do not see what it is to gain by it. It is an exaltation of the martial spirit of the country from which despotism draws its natural support, and before which the genius of liberty stands rebuked and humbled. Such, at least, are the grosser developments of the system on the Continent ; and the same principle, in a modified form, will be exemplified in the augmentation of the military power in this country.

” For the ‘ Iron Duke ‘ individually I have always felt a cold respect (who would have any warm attachment or enthusiasm for an iron man ?) If such work as he was engaged in be again taken in hand by this nation, we shall not find an abler, or an honester, or a more disinterested instrument to carry it to a successful issue. But I cannot join in the exaggerated tribute to the Duke as the ‘ saviour ‘ of his country ; and as for his saving the continent of Europe, I don’t understand why we should save some one hundred and fifty millions of people, who, if worth saving, would have done it themselves when opposed to thirty millions of Frenchmen.

” But as for the ten thousand times repeated nonsense about Wellington saving this country. Nelson did that at the battle of Trafalgar before we began our military career on the Continent ; and from the day on which that great naval victory destroyed the fleets of Napoleon, we were as safe from invasion as if we had been inhabitants of the moon. We spent four or five hundred millions after that decisive battle upon purely Continental objects.

” I repeat that the Duke did his work to perfection ; he neither jobbed, nor lied, nor intrigued like Marlborough, nor cursed and bullied like Blucher, nor boasted in melodramatic strains like Napoleon. But it is pure ignorance that prompts all this fustian about his having saved England, and it is only in the spirit of vain-gloriousness that we could persuade ourselves that, with our forty to fifty thousand men on the Continent (we never had so many probably as the latter at one time), we rescued one hundred and fifty millions from oppression.

” However, the old leaven is fermenting again, and it must work itself out ; and unless we peace people and financial reformers hold a discreet silence until the paroxysm is over, we must expect to be hooted.

“You must let me know what our friend Hume is talking and thinking about. I wrote to him on my return from the North, and gave him some information about Rajah Brooke, which I thought he would be thankful for ; but I have heard nothing from him since. You will find the suffrage question a dead horse just now. It will come to life again some day. The ballot has some vitality in it with the middle class. I have advised people in all localities where I know stirring men to get together facts showing the evil workings of open voting at the last election. I have also advised a central committee for collecting these facts to a focus. I hear that your Society is doing something of the kind; but I should like to see a separate committee at work by way of giving increased force to the advocacy of this question. Depend on it, the powers that be will give universal suffrage sooner than the ballot.

” You cut out the very heart of the aristocratic system in applying the principle of secret voting. My wife joins me in kind regards to Lady Walmsley and yourself and the young ladies, and believe me,

” Faithfully yours,

“R COBDEN.”

With the autumn deepened the national apprehension. The press added fuel to the fire by circulating stories of French naval preparations. Mr. Cobden’s letters throughout this period rebuke and deplore the popular excitement.

Thus he writes on the 2nd of October :

” My dear Walmsley,

“ I am afraid you have been allowing the alarmists to frighten you about French designs. It is all a matter of opinion upon which time alone can decide, but I record my firm conviction, that go far from the President or any other Government of France seeking to provoke hostilities with England, so impressed are they with our undoubted superiority at sea — a superiority greater incomparably since the invention of steam navigation than before — that there is nothing they will so much strive to avoid. If we get into collision with France it will be about Belgium, Sardinia, or some other Continental interests.

” But at all events, let the danger be what it may of invasion or attack from France, let us at least be agreed that it is by sea, and nor upon land, that we are to be prepared to repulse the enemy. Once for all I say, if we are in danger (which I don’t believe) of an invasion, I am willing to be prepared with any amount of force at sea to repel it. Nay, if necessary I would agree to have a boom of ships of war, rafts, and gun-boats all round our southern coast. But you must satisfy me of the danger before I agree to that, and before I agree to anything being done, I must see all the large ships of war we have now got in distant stations moored near our own shores If you are alarmed (which I am not), you ought to call out for the return of our Mediterranean fleet to begin with. But let us not so far depart from our old habits as to allow the aristocracy to fill our land with soldiers officered by themselves, under pretence of protecting us from the French, for that is not the course likely to promote liberty. Sailors are not like soldiers, the ready instruments of domestic tyranny.

” You are under a mistake about my raising a ballot organisation. I have no personal aim in the matter. I don’t intend to put myself at the head of any fresh movement. I urged the formation of a Ballot Committee to collect information from all parts of the country respecting the ends of open voting, as disclosed at the late election. I have everywhere, when possible, urged the formation of local societies of the same kind and with similar objects in England, Ireland, and Wales. I urged upon some men in the Reform Club, whom I met there (such as Torrens, McCullagh, Haly, &c.) to work in this matter, and I advised them to try to bring Grote out of his shell, to give fresh force to the movement. So far from wanting to supersede our Society, I advised McCullagh to consult you in the first instance. In fact, if you can do the same thing through our Society (which I doubt, for I am not satisfied that we have a sufficient ramification or influential support in the country), it will not require to be done elsewhere. The ballot will be the greatest difficulty to surmount. You have expressed yourself satisfied with Lord John’s five-pound franchise, if made a crucial test, which is not a difficult point to gain. Our object should now be to screw the Whigs up to the ballot, which can only be done by our showing a wide and deep public interest in the question. Hume does not seem to differ with me, judging by the enclosed, which I have just cut out from The Hull Advertiser.

” Ever yours truly,

“R. COBDEN.”

Here also let us insert another letter, still further illustrating what favourable results Mr. Cobden expected from the ballot :

” Midhurst, 16th October, 1852.

“My dear Walmsley,

” If I can put a spoke in Fox’s wheel, when in Lancashire, I shall be right glad to do so. I can’t bring myself to believe that a sufficient number of Oldham Radicals will be found to stultify themselves by voting for a Tory to defeat our excellent friend.

“ I hope you are taking advantage of the present favourable moment for giving an impulse to the ballot question. The machinery of the Reform Association ought to be employed in collecting information and arraying the forces, so as to take advantage of ‘ flood tide which leads to fortune. ‘

” There is no doubt that the Liberals of England, Wales, and Scotland are now enthusiastic in favour of a ballot movement. Don’t give in for a moment to the cry that the advocates of secret voting seek to shelve the other points of Hume’s programme. They are the only people who are really in earnest for any reform. You are, I see, about to visit Hume. He seems most anxious to prevent the Whigs coming back to office, without being pledged to a specific policy from which the people will gain something.

” The only way to gain his object is by making the ballot- the ‘ sine qua non.’ All other points of the Reformers’ creed the Whigs will dally with, and to some extent concur in. They will avow themselves for extension of suffrage, more equal distribution, no property qualification, and even shorter Parliaments. These are points in which they can agree and yet compromise them with the Lords as they did before.

” But the ballot, which is worth them all, can be neither frittered away, halved, nor quartered. It is ay or no to the entire measure. Doubtless it involves a larger and fiercer struggle to make a stand upon the ballot; it may require that we should keep the Whigs for years in opposition. So much the better.

” They and we are never so useful as when in opposition. I am. sorry to see the tone of The Daily News about our preparations for repelling a French invasion. The insertion of club letters from old soldiers, provoking a panic again, appears to me to be playing the game of the Horse Guards and the aristocracy, and to be putting the so-called Liberal party in the position which they never ought to occupy. If we are to be made to endorse our present warlike expenditure, and even to call for greater armaments, what policy have we to offer the public which can promise any reduction of Government expenditure ? But I forget I am writing to one who shares in the apprehensions I am deprecating. Let me try to convert you by the way. Read the enclosed very carefully, and talk the matter over with Hume, but do not write to me again about discontinuing my peace agitation. “

” Richard Cobden.”

The Queen opened Parliament on the 11th November, and the struggle at once began. On the 23rd, Mr. Charles Villiers submitted a resolution that the Act of 1846 was a wise, just, and beneficial measure, and that the further extension of the policy of Free Trade best suited the prosperity and welfare of the nation. This was opposed by Mr. Disraeli, who declared the intention of Government to resign if the measure were passed in its present form. Mr. Villiers then brought forward a modified resolution, already assented to by Mr. Gladstone. This was carried by a large majority, and thus Government fairly renounced protection, and took the Free Trade pledge.

Beaten on the question of the Budget, ministers resigned after ten months’ tenure of office, and Lord Aberdeen’s coalition ministry succeeded. What Mr. Cobden’s appreciation of it was, will be seen from the following letter :

” The Government is, I suspect, a fair representation of the state of public opinion, i.e. an agreement upon Free Trade, and no decided views upon any other question. The Cabinet is strong in men, but men of most heterogeneous views, and as they are nearly all leaders, it is just the Government in which you may expect a quarrel They have nothing to fear from without at present. I am very much disappointed at the course things have taken in London, Carlisle, Oxford, &c., where candidates have been allowed to walk over, whilst opposing the ballot. “

” In Oxford and Carlisle we have lost two votes upon this question ! I attach little importance to the promised Reform Bill. There will, of course, be something proposed, as like as possible to Sir John’s abortive scheme, and which the Lords will deal with as they please, and the country will take little interest in the matter. To carry the ballot, without which anything else is mere sham and of doubtful use, will require lectures and an organisation in every town. To judge by present appearances, you and I shall not last (politically) long enough to see it carried. ”

In the midst of all these political changes, the opponents of Sir Joshua Walmdey and Mr. Gardiner made another attempt to deprive them of their seats. Again a petition was sent up to Parliament against their return, and again a Parliamentary Committee was appointed to try their case. It sat for six days in the early part of April On the seventh, before the case for the defendants had opened, the petitioners against them unreservedly abandoned their charges, and, through their leading counsel, withdrew every imputation upon them and their friends.

We shall conclude this chapter with one more letter of Mr. Cobden’s. Mr. Cobden saw plainly that the apprehension of war in the first place, and the interest in it in the second, would seriously impede the progress of Reform. In August he wrote to Sir Joshua, expressing his fears :

” Assuming that the Government intend to bring in a measure next session, which I suppose they must, unless public opinion can be directed to foreign politics (the oldest device in the world, but which John Bull seems ready enough to swallow), then it is undoubtedly the duty of all Reformers to be at their post, and endeavour to force the Government if it be unwilling, or to help it if it be so inclined, to make it a real and not a sham Reform Bill of our representative system. It appears that you are, beyond most men, pledged to such a course, unless you formally disband your Association ; for when or how can it possibly be of use, if not during the next six months ? I know of no plan for a general co-operation, which is what is most wanted. “

” Bright, in his letter to me yesterday, merely observes : ‘ I suppose there will be nothing doing about the new Reform Bill till November.’ Your old friend sent me a pamphlet yesterday about the ballot, with a note saying that he was giving much of his time to it, and wanting me to give him the names of any persons in Manchester likely to co-operate. I advised him to go or send a deputation to Manchester. This is the question upon which there will be the most determined resistance on all sides on the part of the aristocracy. It will not be carried without the same pressure as that which repealed the Com Law, and it will be accompanied by the same break up of parties, and an overthrow of perhaps more than one Government. “

” Believe me, faithfully yours,

” R. COBDEN. ”