CHAPTER XXII. This is perhaps the oddest of any of the chapters in the book. To explain some of the context, I’m going to let Ian Buruma explain at little, followed by James Buchanan’s biographer,Jean Baker, in her 2004 book. What on earth a British M.P. was doing there is absolutely extraordinary?

” It must have been quite a party. The anniversary of George Washington’s birthday: February 22, 1854. Mr Saunders, the American consul in London had invited the leading European political exiles for dinner with James Buchanan, the ambassador and future president of the United States. This would show the old countries which side the new world was on. The guest list was a roll call of the failed 1848 revolutions: Lajos Kossuth from Hungary, Alexandre Ledru-Rollin from France, Stanislaw Worcell from Poland, Alexander Herzen from Russia, and from Italy the triumvirate of Mazzini, Garibaldi, and Orsini. Karl Marx was not invited. he represented a faction – known by his critics as the “sulphorous gang” – not a country, and even if he had been invited, he surely would have despised the others as a bunch of bourgeois wets. In Herzen’s memory there were no German guests at all ……”

” As with most good parties, this one had various subtexts. For one thing, the Americans had to reconcile their own not wholly liberal sociopolitical arrangements with their professed alliance to the “future federation of free European peoples. ‘ Herzen, who enjoyed such ironies, described the occasion as “ a red dinner, given by the defender of black slavery….. ‘. ” from Anglomania: A European Love Affair By Ian Buruma [currently editor of the New York Review of Books}

James Buchanan became President of the United States in 1856 and his biographer Jean Baker says of him: ” Americans have conveniently misled themselves about the presidency of James Buchanan, preferring to classify him as indecisive and inactive … In fact Buchanan’s failing during the crisis over the Union was not inactivity, but rather his partiality for the South, a favoritism that bordered on disloyalty in an officer pledged to defend all the United States. He was that most dangerous of chief executives, a stubborn, mistaken ideologue whose principles held no room for compromise. His experience in government had only rendered him too self-confident to consider other views. In his betrayal of the national trust, Buchanan came closer to committing treason than any other president in American history. ” Jean H.Baker, James Buchanan, Times Books, New York: 2004. It’s not too fine a point to hold Buchanan as largely responsible for the American Civil War.

Now Chapter XXII:

We have now to introduce a scene of an extraordinary character, of which, happily Sir Joshua has left an account in his own words, in which he was brought face to face with the great foreign revolutionary leaders, and of whose appearance and manner he made at the moment some slight but vivid sketches :

” One morning, in February, 1854, “ he narrates, “ a gentleman was introduced into my study. On looking at his card, I found it was Mr. Saunders, the United States Consul. We had never met before. He intimated to me that his object in calling was to invite me to meet Mr. Buchanan, the American Minister, and some political friends. It was against my rule to accept invitations of a political or party character. I asked Mr. Saunders who the guests would be; the list was as follows: Mazzini, Garibaldi, Louis Kossuth, Walsh, Pulski, Ledru Rollin, Count Woxcell, and Orsini. I could not resist this catalogue of fiery names, and accepted the invitation. “

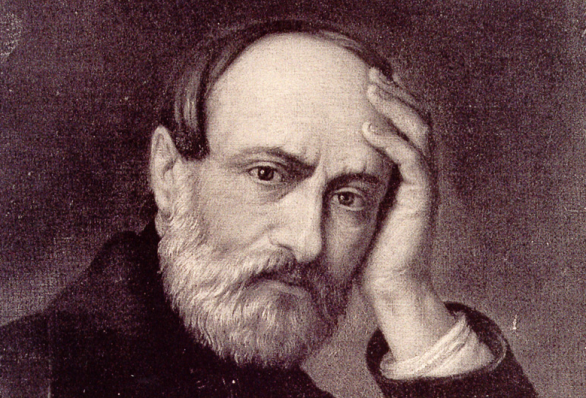

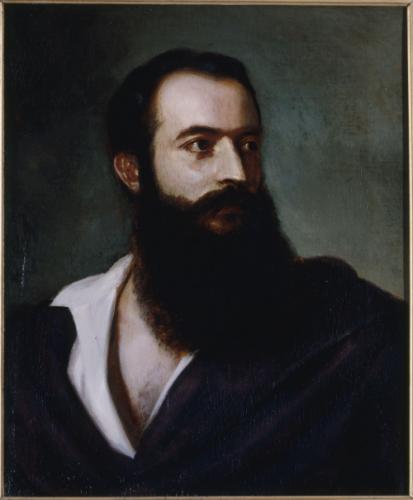

” At 25, Weymouth Street, Portland Square, the singular gathering took place. Mazzini sat at our host’s right hand. His appearance was very impressive and characteristic His eyes burning in his wasted countenance, his high, narrow forehead, spoke of a mind lofty and pure, but wanting in variety and flexibility. His whole appearance indicated a man of few ideas, but these ideas sublime and true. It was a never-to-be-forgotten sight, this group of patriots assembled together — the simple, manly, honest face of Garibaldi, the attenuated features of Woxcell, the grave and handsome countenance of Kossuth, the beautiful young head of Orsini. The dinner was genuinely American in the abundance and costliness of its service. The wit, the humour, the vivacity of the conversation, were delightful, but so long as servants were present, I knew the talk was superficial. “

” When the cloth was removed and the servants had left the room, the doors were closed. I noticed they were double doors. Then a toast was given ; it was to ‘ Humanity.’ Mazzini was the first to speak. His austere eloquence lit with flashes of enthusiasm, profoundly impressed me. It was like listening to the utterances of the old Hebrew prophets. He sketched the dark part of humanity, trodden down by kings and priests. Then came the struggles of the people for liberty. He saw streaks of the dawn in the present. In the future lay the glorious day of a regenerated humanity, free, self-respecting, on whose banner the word “ Duty ‘ was inscribed. It was from his beloved Italy that he looked for this new revolution to come. “

” Each one of the party, after him, rose and addressed the gathering. And the theme of every speaker was his country’s sufferings in the past and present, and his aspirations for it in the future. All spoke freely, as men who had cast off restraint, and who were convinced of the accomplishment in the future of their object. In discussing their country’s wrongs, they frankly discussed the means by which they proposed to redeem and deliver her. From these means I should ever shrink. But at such a moment the reasoning power of the listeners was carried away on this torrent of fiery zeal, impassioned patriotism, and persuasive eloquence. As patriot after patriot spoke, each seemed to press on to a higher and ever higher view of the subject in hand. “

” After Mazzini, Kossuth addressed us in a speech full of power; but his eloquence was more flowery than Mazzini’s, and left less impression upon me. He was too much of a poet to guide up the dangerous height to which he had climbed. His friend Pulski was more of a man of business, and ever proved himself a sound patriot. “

” Of all that night’s discourses, Garibaldi’s simple and straightforward words moved me most. He seemed to take the wisest view of the course to be pursued, and to bring to the service of the subject the greatest amount of practical knowledge. His address, more unpretentious, was, to my mind, more convincing than the others. Orsini looked like a man inspired by, and resolved upon, his purpose. He spoke with much seeming sorrow of the necessity for deeds which he himself was prepared to accomplish. I shall never forget how young and handsome he looked that night, and I am persuaded that the wisest course Napoleon could have pursued would have been to have pardoned him.

” Of Ledru Rollin I did not conceive a high idea. The impression he made on me was that of a disappointed politician rather than of a patriot. Count Woxcell represented Poland. An exile for many years, he was so poor as often to lack the necessaries of life ; yet he never complained. That night he had evidently risen from a bed of sickness. His fine features contrasted with the exhaustion and feebleness of his frame ; death was stamped on his countenance ; but his mind was bright with hopes of his country’s redemption. As he spoke of Poland’s sufferings, tears flowed down his pale cheeks. “

” When it came to my turn to speak, my heart was full of sadness. The words I had listened to were pregnant with poetry, patriotism, and love of humanity. They all emanated from men singularly gifted ; many whose private life I knew to be most estimable, and whose friendship it was a privilege to possess; and yet they all seemed to me to lack the one great, needful quality — a due sense of the responsibilities they proposed to incur. I felt that I, a cold, practical Englishman, could bring only my meed of common sense to sober their enthusiasm. I condemned and at the same time I sympathised with them ; each I knew was ready to undergo martyrdom for the sake of that which he believed to be his mission. “

” As I listened to them and noted the exalted expression of their countenances, the intellect and emotion that lit up their features, genuine sorrow came over me. It seemed a presentiment of the failure of all their plans, of the cruel fate that awaited some of them. I rose to speak, overwhelmed with diffidence and grief ; but I spoke out frankly what I felt. I told them that the constitutional changes the Liberals in England were seeking to obtain would not be difficult to accomplish, when my countrymen became convinced of their utility; and, therefore, our mission could not compare with theirs. I had listened with delight to the eloquence around me ; but I was unable to divest myself of the belief that the speakers were poets rather than statesmen. “

” They proposed to compass their ends through bloodshed, and yet, should they carry out their object, after inflicting great human suffering, they would find the large mass of the people wholly unprepared for the changes they contemplated Instead of a baptism of blood, it should be a baptism of education that should usher in the new era. Sudden changes in the social condition of any people had ever been followed by a great recoil, and if we would permanently benefit mankind, it must be done by steady and continuous education. “

“ The patriots listened in courteous silence. My words, as I feared, had jarred upon them. I was reassured and delighted, therefore, when Buchanan rose, and said he had listened to many speeches that night, but the one to which he had listened with most pleasure was that of Sir Joshua Walmsley. He then dwelt upon the necessity for caution, pointed out to the exiles the obstacles in their way. He did not appear less earnest than any who had preceded him, but he opposed all violent courses. The patriots assented to all he said. But the spirit of the meeting was chilled, a cloud had passed over it. “

” This extraordinary social and political gathering left a twofold indelible impression upon my mind. These men were honest, earnest, truthful, capable of achieving great good in their generation ; but they were unfit to wield political power. They were men of abstract ideas, wanting in flexibility, and therefore unable to deal with new conditions and circumstances as they arose in the world. ”

The forebodings that had come over Sir Joshua’s mind that night were but too surely realised. Woxcell died in the course of the year, in his humble garret, far from the Poland he loved. A few years later, Orsini’s young head fell on the scaffold. It never has been reserved to Kossuth to strike the blow for Hungary’s freedom, that he had longed and waited for and prepared himself to strike, Garibaldi was to taste captivity. Mazzini was to know the isolation, drearier than death, when friends drop away from the patriot and idealist, because he is unpractical.

[There is an entertaining footnote at this point: ” It must be observed that this was written before Garibaldi’s subsequent triumphs, and which were brought about by other means than those contemplated at this strange but pathetic symposium.” The triumph being the re-unification of Italy, finally achieved with the fall of Rome on the 20th September 1870. Felice Orsini had been guillotined in Paris in 1858 for attempting to assassinate Napoléon III ]

After the Crimean War, the bitterness of exile was more than ever felt by Kossuth. The conviction forced itself upon him that he would never again be of use to Hungary. In 1856 he writes to Sir Joshua : “ I may have sown for the future ; but the day of harvest I am not to see. I feel I can do nothing more for my country. “ The very hope of seeing it again died out. When this hope was gone — that had been the consolation of his soul through the protracted years of exile — his heart nearly broke.

He had in his children, however, an incentive to work. We find him writing in The Atlas, and partly managing it. Acting under Sir Joshua’s advice, he delivered also, during this period, courses of lectures in the principal towns of England, which drew crowded audiences around him. Some years passed thus, and on 2nd March, 1861, he wrote as follows to Sir Joshua :

” 12, Regent’s Park Terrace,

” Dear Sir Joshua,

” Irrespective of the contents of your two friendly notes, I was very, very agreeably surprised by receiving again your handwriting, once so familiar to me, now not seen for a long time. Your withdrawing from town on the one hand, and the fluctuations which the stirring events of these last years had thrown me into, caused us to lose sight of each other. I, on my part, have maintained, as I always shall, a lively and grateful recollection of our past intercourse. I never ceased to cherish your name as one of those few, but dear friends, who stood faithfully by me in many gloomy moments of my cheerless life, who never wavered in their sympathies through good and evil report, and whose kind advice never failed me in the hour of need. And I see, I rejoice to see, that you are still the same as of yore ; we had lost sight of each other accidentally for some time, yet the first line I receive from you bears again the stamp of your old, still unabated kindness. You never approached me but to do me good, and so you do now…….

“We are about to bid adieu to good, dear old England ; and all of us feel deeply moved at the very thought. I have grown old on its hospitable soil, and my boys have grown from children to manhood on it. It has been endeared to my heart by many ties of imperishable interest ; the protection afforded to my homeless head; the flowers of consolation strewn on my thorny pathway; the inappreciable, still, joys of domesticity ; the recollection of the very hardships I had to overcome and the very cares and sorrows I had, that were mingled with my aspirations as with my daily bread — make England so very, very dear to me, that it is with a pang of melancholy feeling that I part with her. It may be for good, it may be for evil, that I do so ; but I must, so let come what may, it shall be endured.

“ But is not it strange, that to make my cup of vicissitudes full, I have in the very last days of my stay in England to pass through the ordeal of a suit in Chancery, and that too at a Bill of Prayer and Complaint filed against me, by whom? By Francis Joseph, the pretended King of Hungary,

“ Chancery! To be in Chancery is a word of terrific meaning, even to Englishmen, who are used to this ‘peculiar domestic institution:’ the very name of it adds heavy items of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of pounds to one’s budget. My antagonist may have calculated on my incapacity of meeting him on this expensive field, or may be bent on ruining me, before I have waded across half of it. And in this also, he is not unlikely to have made a good account I may break down (not much strain is needed to bring me to this), but ‘ gli prometto la fede mia,’ it shall not be done before I have brought him to such odds with public opinion in this country, that all his speculations on an eventual support from England shall have vanished like a dissolving view. . . .

“ With many affectionate regards,

” I am, dear Sir Joshua,

” Yours very truly,

“Louis Kossuth. “

And here the figure of the great Hungarian patriot drops out of our narrative. Looking at Hungary,as she now stands, in recovered full possession of her antique constitutional rights, the violation of which had driven Kossuth to take the field, may we not say that his prediction as to the day of harvest has been fulfilled ? The day Francis Joseph had to submit to being crowned King of Hungary, in Pesth, and there solemnly swear observance of all her privileges, Kossuth stood vindicated in the eyes of history. Nor were his efforts in England vain. Through his speeches the people at large were made acquainted with the character of the question at issue, that it was one involving laws and religion akin to their own, and doubtless English sympathy with the Hungarians, and English example of combat by moral means, encouraged and inspired the opposition party in the Hungarian Diet under the leadership of Deak, to which eventually the House of Hapsburg was obliged to yield.