CHAPTER XXVII. This is yet again a very political chapter, with almost nothing about the family. By now Josh and Adeline are grandparents of four granddaughters, – all the daughters of Elizabeth Walmsley and Charles Binns. The girls range in age between seventeen year-old Adeline and eight year-old Emily. Three more granddaughters and one grandson follow in the 1860’s and 1870’s. At the time of the election, Josh is sixty-three.

Early in March, 1857, the following requisition, signed by one thousand three hundred and fifty-two electors of Leicester, was presented to Sir Joshua :

” We, the undersigned electors of the borough of Leicester, deem it our duty, under existing circumstances, to assure you of our confidence in your general conduct as our representative. There are points of difference between some of us and yourself, but your devotion to the interests of the constituency, your unflinching advocacy of all measures calculated to promote civil, political, and religious equality in the eye of the law, and your independent parliamentary conduct, so greatly outweigh these points of difference, that we request you will, whenever Parliament shall be dissolved, offer yourself for re-election, when we have the fullest confidence that the constituency of this borough will again triumphantly return you as one of their representatives. ”

” Leicester, 28th February, 1857. ”

The above requisition had been resolved upon at a large and enthusiastic public meeting at the New Hall, where the vast assembly had recorded a unanimous vote of confidence in Sir Joshua Walmsley ; coupling with his name that of Mr. John Biggs, who had succeeded to the representation on the sudden death of Mr. Gardiner, in June.

” This strong expression of feeling, “ says Sir Joshua, ” was called forth by the report that, at the following election, I would be opposed by Mr. Dove Harris, now brought forward by the Whigs and several influential townsmen. I had made enemies for myself by the course I had pursued in Parliament. “

” The warmth with which I had espoused the interests of the stocking-weavers had alienated from me the manufacturers of the town. My earnestness in the cause of Electoral Reform had rendered the Whigs as inimical to me as the Tories. These points of antagonism were, however, limited to certain sets of interests in the boroughs ; outside of them I had fast friends. My advocacy of the claims of the frame- work knitters had also drawn warm hearts to me; and among a liberal constituency the extension of the franchise being held to be a just and necessary measure, I, who had succeeded Joseph Hume in advocating it in Parliament, was consequently popular. “

” It would have taken something more than the banding together of the manufacturing interest and the old Whigs and Tories, to deprive me of the esteem of a constituency whose interests I had devoted myself to and laboured for during five years, whose political battles I had fought, whose political debts I had paid, and towards whom I had redeemed in letter and in spirit every pledge I had taken. “

” One cry there was, however, that had in it potency enough to rouse every sect and interest against me -the cry of the ‘ Desecration of the Sabbath.’ I had moved in Parliament for the opening of the museums on Sundays after church hours. I was president of the Sunday League. The clergy joined their vituperations to those of the manufacturers and Whigs ; and to crown these, the Tories promised to support the candidate brought forward to oppose me. ”

Timid spirits quailed before this rallying cry of the Opposition. The frame-work knitters, unfortunately outside the pale of representation, never swerved from their allegiance to Sir Joshua Walmsley . That much-abused ” Sunday cry “ had in it a ring of sympathy with the overworked multitude ; and they from their hearts wished him to succeed over his rivals.

Parliament was dissolved the first week in March [1857]. On receiving the above address, Sir Joshua consented once more to stand for Leicester. Free trade, popular education, liberty of conscience, a wider extension of the suffrage, were still the four cardinal points of his political creed recapitulated in his address to his constituents.

At a public meeting on the 16th March, he explained the position he meant in the future to take in relation to the question of opening the museums on Sunday. ” I regard it as an educational movement, and my advocacy of it is based upon my earnest desire to do justice to the working classes in the metropolis. I am not here to enter into the merits or demerits of the question — one upon which many of the most pious, talented, and virtuous ministers of the day do not agree. But I am free to admit that with such an expression of public opinion against me on this question, I should not be justified were I to bring it, under existing circumstances, again before the consideration of Parliament Further, I am bound to say, with all honesty and sincerity. I have not altered my opinion upon it one iota. All that I did believe I continue to believe ; but now that it is taken up adversely by a great body of those who have been my earnest and warmest supporters, men whom I esteem and who are esteemed and beloved by their fellow-townsmen, I should, if it were again brought before the House of Commons, tender my resignation to this constituency; before, I felt in a position to support it, or to bring it before the House.”

This declaration on the Sunday question did not pacify Sir Joshua’s opponents. The struggle began in right earnest ; and, ” for a fortnight, “ to use the words of The Leicester Mercury, ” the town was divided against itself by an election contest approaching in bitterness and violence to an implacable civil war. “ Placards covered the walls denouncing Sir Joshua as an infidel. The clergy held meetings, where resolutions were passed of uncompromising opposition to the candidate favourable to the principles of the Sunday League.

The Whigs united with the Tories against the Reformer, and the manufacturers, resenting the part he had taken in the House of Commons in the frame-rent question, joined the other factions. Regardless of the antagonism and the misrepresentations rife on all sides, Sir Joshua persisted in his canvass. The poor frame-work knitters felt his cause was theirs and as he passed their cottage doors they, at all events, wished him ” God speed. ”

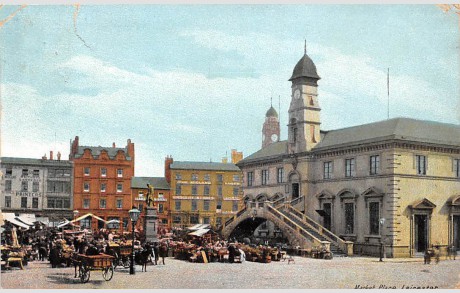

Friday, 27th March [1857], was the nomination-day, and a multitude filled the market-place. The cup of indignation was full to the brim when Sir Joshua saw how old friends had become enemies, how former political supporters had gone over to his opponents. His speech that morning exposed the inconsistency of those who some years ago had been his allies. ” Those gentlemen brought me to this town, having known me for nearly twenty years ; they then supported me, and glad and proud I am that they have not been able to bring one accusation against me. What did I pledge myself to on that occasion ? That in matters of commercial policy I should be, in the fullest sense, a free-trader ; that in matters of religion and education I should contend for perfect freedom and absolute equality ; and that, as regards the improvement of their representative institutions, I should advocate the scheme of reform embodied in Mr. Hume’s annual motion, which aims at securing the representation of every class of the community. I have fulfilled these pledges. ” He went on to give a rapid sketch of the course he had followed in Parliament, showing that he had never swerved from the path he had pledged himself to follow. He spoke with great earnestness. Some twelve or fifteen thousand persons were assembled in the market-place, of which the great mass were non-electors, eagerly watching the proceedings of the day, and determined to pronounce their sentence, which they knew on the morrow they would be unable to record. At the close of all the candidates’ speeches, a show of hands being called for, the vast crowd arose, and an immense demonstration of feeling ensued in favour of Sir Joshua Walmsley.

The decision of this meeting was reversed next day in the polling-booths. The extraordinary excitement that had possessed the town for a fortnight reached its climax when the result was declared at four o’clock. The coalition had triumphed. Sir Joshua Walmsley was defeated. The votes were as follows :

1618 for Mr. Dove Harris,

1609 for Mr. Biggs,

1440 for Sir Joshua Walmsley.

Soon after the result was known, a concourse of people assembled in front of the hotel to hear the defeated candidate’s farewell words. An eye-witness described the assemblage as extending nearly the whole length of the street, computing it to have numbered some twenty thousand. This hotel was then the leading one in Leicester — a long, low, straggling building of the reign of Queen Anne. It has since been pulled down to make room for a handsome bank and other buildings. In a few words Sir Joshua — after thanking the assembly for the manner in which they had stood by one who was “ opposed, not only by Tories, but by Whigs, who, deserting their colours and their principles, arrayed themselves against a man who, as far as he has been able, has stood forward here and elsewhere, during the whole course of his public life, to maintain, to the best of his ability, the rights and privileges of his fellow- countrymen “ — then urged those present ” to unite hand and heart to carry out those great principles which secured to every man, who has intelligence enough to value it and exercise it, and who pays his rates and taxes, a right to vote for the man of his choice. ”

“ Yesterday, “ he went on, ” nine out of ten of the men of Leicester held up their hands for me ; and what would have been the result to-day if you, the hard- working, honest-hearted men of Leicester, if your votes had had weight in the balance ? May this be a lesson you will never forget. Remember they have defeated the man of your choice. “ Sir Joshua’s closing words enjoined to ” forget and forgive, “ while strenuously and peacefully striving for a juster state of things.

But all that night the town was excited, and bands of frame-work knitters paraded the streets, shouting Sir Joshua’s name. The Leicester Liberal papers next day teemed with expressions of regret at the defeat of the popular candidate. It was now decided that an address and a testimonial should be presented to Sir Joshua. The working classes especially responded to the movement, throwing their whole hearts into the work, to show honour and affection to the man who had devoted all the energies of his public life to the cause of justice, liberty, and true fraternity. Many were the wives of the stocking weavers who appended their signatures to the address of the women of Leicester, and who subscribed their pence to the testimonial to be presented to Sir Joshua Walmsley on his removal from the representation of the borough of Leicester.

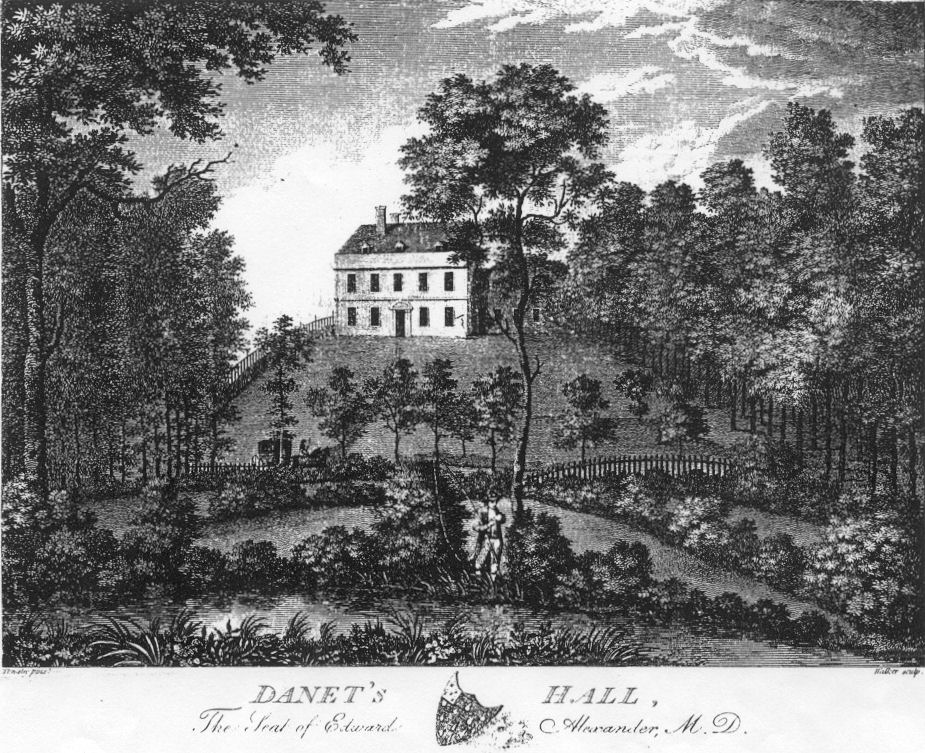

On the 23rd of June [1857], the day fixed for the demonstration, long before noon, some thousands were assembled in front of Danett’s Hall, where Sir Joshua and Lady Walmsley were staying as guests of Dr. Noble. These electors and non-electors were waiting to escort the defeated candidate to the market-place. At half-past twelve the procession fell into rank. With some difficulty it made its way through crowded streets, that wore the aspect of a popular festival. Flowers festooned the houses ; flags and triumphal arches, bearing mottoes and greetings, decked the route. The cheering multitude, the bursts of music, the beauty of the day, made up a spectacle of brightness and cordiality that removed much of the bitterness that was naturally associated with this Leicester episode of Sir Joshua’s life.

A vast throng awaited the procession in the market-place. The Leicester Mercury estimated the numbers present at between twenty and thirty thousand. The testimonial, a centre-piece of massive silver, artistically designed, and two addresses — one signed by six thousand seven hundred and fifty women, and the other by five thousand six hundred and sixty- five electors and non-electors — were then presented.

There was also presented to Sir Joshua the pure white flag the ladies of Leicester had embroidered for him and Mr. Gardiner, on the occasion of the defeat of the petition against their election in 1852.

” I feel ,” said Sir Joshua, in the course of his brief speech of hearty acknowledgments, ” that this demonstration is a complete and ample reply, rebutting the calumnies recently circulated against me. ”

A public soiree was held that evening in the Temperance Hall. Although the largest hall in the town, yet numbers were unable to obtain admittance.

” It would be impossible,” says the same eyewitness whose words we have already quoted, ” to describe the enthusiasm of the assembly, and the affectionate greeting given to Sir Joshua Walmsley. “ Perhaps there never was an occasion on which the feelings of the disappointed majority of the population of a large town was more unequivocally expressed. ”

” We venture to say, “ remarks The Leicester Mercury ” that the proceedings of the 23rd June, 1857, will henceforth constitute one of the most interesting chapters in the history of the borough. Certainly no expression of public feeling was ever attended with more imposing circumstances. ”

Thus closed Sir Joshua Walmsley’s public connection with the borough of Leicester. It was also the closing scene of his public life.

Some time after the hubbub of that day’s excitement had subsided, a deputation of frame-work knitters waited upon him in his house in Westbourne Terrace. They came to thank him for his efforts in Parliament to alleviate their lot, and for his advocacy there of the right of the working-man to the franchise. They asked to be allowed to present Lady Walmsley with a pair of gloves or mittens they had woven in silk for her.

This humble testimonial was preciously kept by Sir Joshua, side by side with the silver centre-piece and the embossed addresses that had been presented to himself.